At Vancouver Writers Fest, Jen Sookfong Lee reflects on the pop culture that shaped her in Superfan

The local author says reality television is the great equalizer in social situations

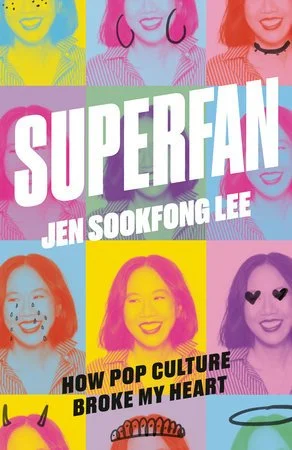

Jen Sookfong Lee. Photo by Kyrani-Kanavaros

Jen Sookfong Lee appears at Using Pop Culture at Performance Works on October 19 at 1 p.m. as part of the Vancouver Writers Fest. At the same venue, she will also appear as part of Smells Like… 90s Lyrics Night on October 19 at 8 p.m.

JEN SOOKFONG LEE may move in literary circles, but don’t let that give you the wrong impression of her. Sure, the Vancouver-born author’s literary fiction has earned her nominations for various prestigious prizes—her 2011 novel The Better Mother, for example, was a finalist for the Vancouver Book Award—and yes, she cohosts a literary podcast.

Like the rest of us, though (go on, admit it), Lee has dealt with heartbreak by blasting Sia’s “Chandelier” on repeat, and she holds a special place in her heart for Bob Ross’s soothing tones and happy accidents.

Reached at her home in North Burnaby, where she has been appearing (virtually) in online events as part of the Whistler Writers Festival, Lee tells Stir that pop culture is not only worthy of serious consideration, it can also be the great equalizer in social situations.

“Whenever you go to a dinner party or wherever, and you’re just trying to make conversation with people you don’t know very well, inevitably what ends up happening is somebody will say something like, ‘Oh my god, did you guys see the last season of Love Is Blind?’” Lee says. “Right? Just to start the conversation. And there’s always that one odious person who says something like ‘I never watch reality television. I only repeat seasons of Succession.’”

Lee herself is not such a snob when it comes to her own viewing habits, as her unabashed love of Keeping Up With the Kardashians makes clear.

“I always find myself having to defend whatever piece of pop culture that I find myself really liking,” she says. “And I would always try to do it in a really personal way, like with anecdotes or stories about why this thing is meaningful to me, and why that thing reverberates throughout the culture. And as I started doing this, I realized that I could actually write a book of all these arguments with friends. So that’s exactly what I did.”

That book is called Superfan: How Pop Culture Broke My Heart (Penguin RandomHouse Canada). In it, Lee uses iconic pop-cultural figures and works—Rihanna, Dead Poets Society, Princess Diana, Justin Bieber, Anne of Green Gables—as springboards to reflect on her own understanding of her various intersecting identities: daughter of immigrants, Asian Canadian woman in a milieu dominated by white men, single mother.

Inevitably, Lee’s relationship to some of these bits of pop culture has changed over time. She cites The Joy Luck Club as an example. Two examples, really: Amy Tan’s original novel, published in 1989, and Wayne Wong’s 1993 movie based on it.

“For so long that book was sort of touted as, or seen as, the definitive narrative on the Chinese diasporic story,” Lee notes. “I really wrestled with that. I’m a bit of a contrarian. When that movie and that book were really, really popular, I was a teenager—sort of prime don’t-tell-me-what-to-do years—so I ended up hating it, to be contrary. I ended up really resenting the idea that we were all supposed to have these bad intergenerational stories between mothers and daughters. Especially when I started publishing books in 2007, that was held up as an example of what Asian women should write about.

“When I initially pitched that particular chapter to my editor, it was really about taking apart the idea of what Asian women could write,” Lee continues. “In the course of that, of course I had to revisit the book and the movie, and I realized, actually, they’re both pretty good! It’s just that the way that people perceived it, or the way people responded to it for many years, were problematic.”

There are very specific reasons why The Joy Luck Club’s intergenerational-conflict themes resonate so strongly with Lee. As Superfan makes clear, the author has had a fraught relationship with her own Chinese-immigrant mother.

Lee knows her mom will not read Superfan—and not just because she never learned to read English. In Lee’s account, she has been largely oblivious to her daughter’s successes but never reticent to call her out for her perceived shortcomings, and those of Lee’s three sisters.

The elder Lee is given to occasional pronouncements like “When I die you will all be happy” and “I am ashamed of you because you have never done anything right.” Mostly, though, she allowed herself to recede into the background after the death of her husband, who was essentially her lifeline to the outside world.

“I never want people to think I’m doing a hatchet job on my mom,” says Lee, whose compassion for her mother comes through even in the bleakest chapters. “I really love my mom. But a lot of this book is the result of years of therapy where I’ve spent a lot of time trying to understand her. And I think in order for me to have a relationship with her, understanding her is the first thing we have to do—I’m speaking broadly of my sisters and me. All my life I’ve been trying to understand her, and that’s what that book is, really.”

It is that, but Superfan is also Lee’s meditation of the stories, songs, and movies that have shaped her. Notwithstanding the fact that some of those things are inextricably linked to painful memories or deep regrets, the book is a celebration of both the joy of new discovery and the comfort to be found in a dog-eared novel or that favourite Ethan Hawke movie you’ve watched more times than you can count..

“That initial feeling of loving something when you’re a younger person, it’s a really beautiful feeling, when you fall in love with something with zero reservations, which is something that doesn’t happen as much when you get older,” Lee observes. “You know, as we get older we accumulate cynicism and all sorts of things. That original feeling, I try to remember and hold onto, because it’s special. That particular relationship that a younger person has with something, even if it’s problematic, that sort of really pure love is a really special thing. And hopefully as we get older, as we all start to question things, we can still at least remember and hold onto that really nice feeling.”