Maestro Leonard Slatkin makes Vancouver Symphony Orchestra debut, as principal cellist Henry Shapard’s life comes full circle

Renowned American conductor leads Spanish Adventures program, while string player performs Don Quixote solo with one of his musical heroes on the podium

Guest conductor Leonard Slatkin. Photos by Cindy McTee

Vancouver Symphony Orchestra presents Spanish Adventures: Don Quixote at the Orpheum from March 8 to 10

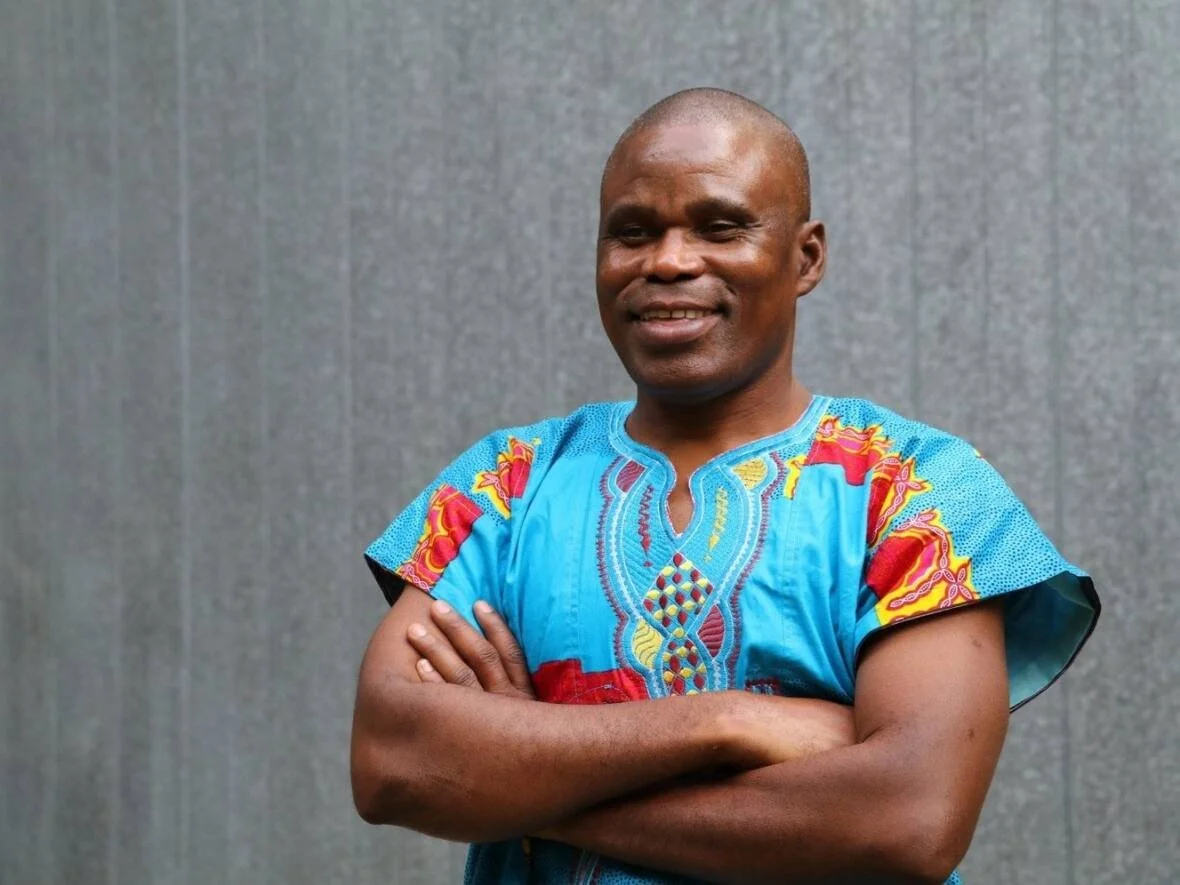

AS A TEEN, THE Vancouver Symphony Orchestra’s principal cellist, 25-year-old Henry Shapard, was gifted Conducting Business, a book written by one of his musical heroes, the renowned American conductor Leonard Slatkin.

“My grandmother gave it [Slatkin’s book] to me for my 12th or 13th birthday,” the Cleveland, Ohio-raised Shapard shares during a short rehearsal break. “He’s somebody I've always really looked up to. Especially for American musicians like me, he's a household name, and a conductor that I had always admired.” Now, his life is coming full circle.

This weekend, Shapard will not only meet his hero, but play under his baton for the first time when he takes on the virtuosic cello solo part of Richard Strauss’s tone poem, Don Quixote. “I'm really, really excited to work with him, even more so on the Don Quixote, which is a piece beloved by cellists because it has all these incredible solo moments,” he says.

Reached in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania during a stop on his rigorous global touring schedule, Slatkin sounds equally enthused about the event, which will mark his debut on the VSO podium.

“They asked me if I would do the Strauss with the orchestra's principal cellist, and it’s a wonderful idea, because that was actually the original intent of the piece anyway,” the maestro says.

He has been in correspondence with Shapard to discuss seating arrangements during Don Quixote, about which the cellist had a very clear opinion.

“Usually, when people see this piece performed…the cello soloist will sit out front, much as he or she would do in a standard concerto,” says Shapard. “But in the way that Strauss actually conceived of this piece, in his idea, it's supposed to be played by the first cellist on the first desk….I felt very strongly that I should try to stick as close to Strauss's conception as possible, so I’m playing the rest of the cello part as well with my colleagues in the VSO.”

Henry Shapard. Photo by Allison Park

To bring things even closer to Strauss’s intentions, Slatkin will have the orchestra positioned with the second violins on the far right of the stage, a position now normally occupied by the VSO’s viola section. “It’ll be first violins, cellos, violas, and second violins, which is how orchestras at Strauss’s time played,” Shapard explains. “It creates an interesting visual effect where you have often passages being sent from one side of the orchestra to the other.”

To round out the program, Slatkin settled on a contemporary work by Mason Bates, Anthology of Fantastic Zoology. “[Don Quixote] gives me a big tone poem with a soloist in it, and it serves to me very well as a closing piece on a program,” the conductor says. “It also gave me the flexibility to do something a little more offbeat, because Strauss is usually fairly good for attracting people.”

He opted to introduce the audience to this piece by a contemporary American composer. “I thought it would be more interesting for the audience to hear one of the younger generations of composers, but in a major work, as opposed to a seven- or eight-minute overture” he says.

The work, a half-hour-long symphony inspired by the mythical creatures from Jorge Luis Borges’s book of the same name, is not without its challenges for the players. There are solos that bounce throughout the desks of the strings, violins playing off-stage—and even a typewriter in the percussion.

“It's an incredibly virtuoso piece,” Slatkin notes, “but I was assured by many that this would be just fine [for the orchestra].” After checking out the VSO’s programming over recent years and asking around, he says, “I realize it's an excellent orchestra.” It’s also one made up of a fairly young group of musicians, he acknowledges: “I guess not so many of the orchestra members will have played anything on the program, much less the Bates. So, for everybody, it's going to be a real learning experience.”

As he prepares for his moment of music-making with Slatkin, Shapard, who joined the VSO in 2020 at just 21 years of age, admits to feeling some butterflies.

“I’m nervous for everything all the time,” he confesses. “I'm nervous for every rehearsal with the VSO. I'm even nervous when I practise. I think part of it is [what happens] when you work with people that you really like and respect. Of course, I enjoy sharing performances with an audience, but the people that I'm most concerned about doing well by are the people on stage who are participating in that project with me. I think there's always this sense that it has to be prepared to an extent that you make life easier for the people who share the work with you.”

Thankfully for Shapard and his colleagues, the days of the dominating, egomaniacal conductor, epitomized by Cate Blanchett in Tár, are behind us. As Slatkin observes, “You can't do that today.…It just can't exist anymore, for many reasons.” Working with orchestras around the world, almost all of which are filled by a young generation of players, he considers himself a mentor rather than an authority.

“Hopefully, I bring whatever I've accomplished and have been able to do with my experience to the orchestra itself,” says Slatkin. “I just try to think of myself as being another musician out there. It’s like any coach of a sports team: somebody's got to say how it's going to go…. I always like to leave a place saying I did something to make them better for the next conductor that's coming in.”

As he turns 80 this September, Slatkin says that he’s not sure how much longer he’ll be conducting. He will, however, keep writing books. His fourth, Eight Symphonic Masterworks of the Twentieth Century: A Study Guide for Conductors, comes out March 5, “and I'm doing a couple more.” All of which should come as welcome news for Shapard, and the next generation of young musicians on the horizon. ![]()