Debate continues over plans for “South Asian Canadian Museum” in Metro Vancouver

As B.C. government asks people to weigh in on venue’s name, location, and vision, some community members remain skeptical of purpose, progress

Mo Dhaliwal. Photo by University of the Fraser Valley

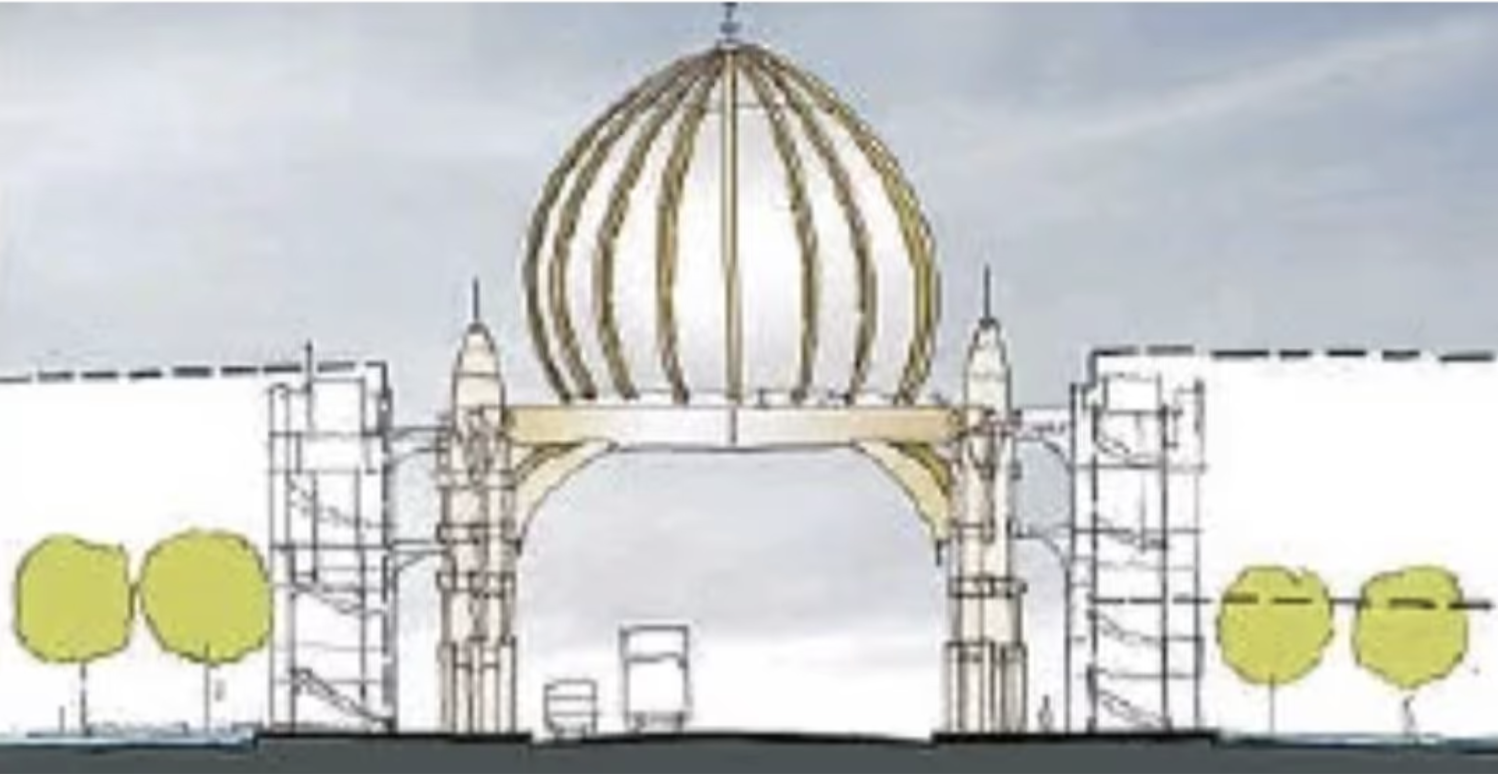

Artistic rendering of the never-built cultural gate for the Punjabi Market on Main Street near 50th Avenue in Vancouver. Photo via Government of BC

IN 2020, THE B.C. NDP government at the time promised a first-of-its kind new museum to highlight the experiences and contributions of people of South Asian descent. Nearly four years later, the province is now moving into a public-consultation phase while some community members remain skeptical about the venue’s plans and progress.

The government has announced that community-designed workshops and an online public survey will begin in early 2024. A new website will provide people with the chance to share their ideas for the museum, which aims to highlight the history, culture, and contributions to B.C. by Canadians of diverse South Asian heritages.

Feedback from the engagement process will be released in a report summarizing key recommendations, themes, and questions, which is to be published in the summer of 2024.

The government is asking people to weigh in on such questions as: What should the museum be called? Where should it be located? And what will be its vision?

The public engagement comes after things got off to a rocky start this past April, when a “South Asian Museum Community Leaders Gathering” at the Wosk Centre for Dialogue in Vancouver was held by Lana Popham, the British Columbia Minister of Tourism, Arts, Culture and Sport. It was by many considered a flop, as first reported by Rungh publisher Zool Suleman, with some community members feeling alienated and others concerned by the terms “South Asian” and “South Asian Canadian” (see below).

Mo Dhaliwal, CEO of Skyrocket Digital and co-founder and director of Poetic Justice Foundation (a grassroots advocacy group targeting oppression and discrimination), is critical of the government’s intentions.

“I’d like to congratulate the government on managing to promise to launch a website at some future date, a full three years into their original commitment to begin the process for the South Asian Canadian Museum—and just in time for the ramp up period to the next election,” Dhaliwal tells Stir. “There has been zero urgency on this file to date. Considering the hurried way in which they are rapidly recruiting advisory members and intending to go into consultation right before the end of government’s fiscal year-end tells me that this is the continuation of an insincere process. The ministry is not interested in consultation. They’ve already decided that our engagement framework and, largely, our museum is going to be a copy and paste of the Chinese Canadian Museum rather than something that is authentic to the diversity of our people. So, rather than consultation, they appear to be recruiting pliable parties who will agree with what they’ve already pre-ordained to be the course of action. This is not consultation. This is not community engagement. This is condescension at best, coercion at worst.

“The museum is a critical institution for the community,” he adds. “Mainstream cultural institutions from academia to archives are colonial projects and racist in their own history and structure—many admit this openly, but are at a loss for how to change. As such, non-white communities in Canada have been left with very little recorded history or artefacts within the very spaces funded by our tax dollars. As well, the socio-economic pressures faced by successive generations of immigrants means that it takes a long time before a community, like the province’s Punjabi Canadians in this instance, have enough time and space to ponder their place within the country and the world. We need a place to harbour over 120 years of narratives and artefacts. We need a place that can act as a living home for our stories going forward, stories that will empower the formation of identities, of belonging, of strength and cohesion for generations to come.”

The government states in a release that the engagement will involve South Asian Canadian organizations and communities, including leaders, youth, elders, entrepreneurs, artists, scholars, historians, and people from diverse social, cultural, gender, and accessibility-inclusive communities.

A ministerial advisory committee on the museum has been established, with 13 members: Am Johal, Balbir Gurm, Haiqa Cheema, Harjit Dhillon, Haroon Khan, Harpo Mander, Jeevan Sangha, Jinder Oujla-Chalmers, Karimah Es Sabar, Parminder Virk, Renisa Mawani, Sahil Mroke, and Upkar Tatlay.

The terms “South Asian” or “South Asian Canadian” are temporary placeholders until a name for the museum can be decided on. These terms “share the virtues and the shortcomings of any broad category”, according to the government.

“These categories reveal as much as they obscure,” reads the statement. “‘South Asian’ can be a unifying term and it can be a divisive term. Naming an institution such as a new museum presents an opportunity to think deeply about the museum’s purpose. Knowing that no name will be perfect or preferred by everyone, what should this new museum be called? What ‘work’ does the new museum’s name need to do? These are the kinds of questions—along with the location, vision, and purpose of the new museum—that we imagine will energize the conversations during this engagement process.”

Dhaliwal says that the spring consultations were a “disaster”, “because the ministry and its bureaucracy continues to be dismissive to the community”.

“Advice on how to approach consultations was not heeded,” Dhaliwal says. “Time and space to put together the first such program was not provided—after sitting on their hands for almost two years, suddenly the ministry decided to ram through an event with a few weeks’ notice. It was apparent in the format of the event that it was for ‘listening and learning’ in name only. I’m not so naive as to think that all of the necessary community engagement was going to be accomplished on that day—of course not. I’m speaking to how we arrived at that event and how it was conducted, because how something is conducted is the truest indicator of the values underlying a process. And the entire process was highly performative.

“The placeholder name of the project as a ‘South Asian Canadian Museum’ needed to be adequately contextualized, or else risk many people in the community feeling erased in that terminology—we knew this would be a concern going into this meeting, because we’re from the community,” he adds. “This was not heeded. Not only that, but after repeated reminders to at least include the word ‘Canadian’ in even the placeholder title, concerns were brushed aside and we were invited to a consultation for the ‘South Asian Museum’—a violently inappropriate name. These might seem like small things, but they are symptoms of a larger disease: White supremacist institutions patting themselves on the back for their good intentions, but proceeding to condescend to us time and again.”

Elsewhere, people involved in Wanjara Nomad Collections—a collection of rare books pertaining to the Sikh rule, East India Company, and the British empire—who were part of the initial dialogue wrote an open letter to MLAs and MPs, decrying the term “South Asian” as “demeaning” and “dehumanizing”, failing to recognize people’s individuality.

“The term ‘South Asian’ is disparaging as it homogenizes and erases the unique identities, cultures, and experiences of millions of people from the Indian subcontinent, reducing them to a generic label that perpetuates stereotypes and overlooks diversity,” the open letter states.

“It is a distressing reality that minorities are frequently compelled to demonstrate solidarity with those who oppress them under the guise of ‘South Asian’ unity,” the open letter continues. “This insidious practice perpetuates a cycle of systemic subjugation whereby marginalized communities are forced to conform to the dominant narrative, even at the expense of their identities and well-being. The deleterious effects of this oppressive tactic are immeasurable and require immediate redressal.”

The open letter also said that calling the institution a “South Asian” museum “would be a grave historical blunder, perpetuating the systemic erasure of distinct cultural identities”, it reads. “Additionally, the museum must ensure the inclusion of unrepresented nations from that region, who are fighting for their survival and sovereignty and have been living in Canada as Canadians.”

The Sikh News Express has issued a call for a separate exhibit for Sikhs.

The new museum is to build on the Punjabi Canadian Legacy Project and South Asian Canadian Legacy Project, which showcased the past and present contributions of South Asians in B.C. Both initiatives were undertaken by the South Asian Studies Institute at the University of the Fraser Valley. The centre’s director, Satwinder Bains, is no longer involved in the engagement process and was unavailable for comment.

Public input, says Popham—especially from South Asian communities—is vital to moving forward on this first-of-its-kind museum.

“The contributions of South Asian communities in B.C. are an important part of our province’s history, culture, and success,” Popham says in an email to Stir. “South Asian Canadian communities have expressed a need for a museum that brings together artifacts, documents, and stories. We are committed to creating a first-of-its-kind museum and we will continue to work closely with South Asian Canadian communities in B.C. to make this museum a reality.

“We are at an early stage of community engagement planning along with community advisors,” she adds. “A community-designed and -led engagement is planned with many opportunities to share input, both in person and virtually. The public will have an opportunity to provide input on the name, location, and vision for this museum. Nothing has been decided yet.”

There is optimism among some involved in the consultations.

“I am delighted and honoured to participate in the groundbreaking work of an innovative and vital new institution for all of British Columbia, a new museum that highlights the living history, vibrant cultures, and contributions to our province and nation from peoples of diverse South Asian heritage,” Haroon Khan, co-chair of the ministerial advisory committee, says in a release. “History is not something that happens, it’s something you make. Let’s make history together.”

Lana Popham.

The establishment of the arts institution is what the government describes as its “cross-government work to collaborate with Indigenous Peoples and racialized communities to dismantle systemic racism and build a better, more inclusive province”, according to the statement.

“For almost 130 years people from South Asia have been calling British Columbia home, but this has not always been a welcoming place for them,” Mable Elmore, Parliamentary Secretary for Anti-Racism Initiatives, says in a release. “By working with community members we can build a unique and meaningful museum that will better reflect and preserve the diverse and rich history of South Asians in the province for generations to come.”

According to the government, the public engagement process is being informed by Simon Fraser University’s Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue and the ministerial advisory committee. The committee is made up of appointed members who identify as South Asian and who were selected for their experience in community engagement, lived experience, and cultural knowledge. Their role is to inform the development of the engagement plan, share opportunities within their communities, and support community-based conversations.

The Centre for Dialogue’s role is to provide strategic advice to the province so that engagement is designed with the “principles of equity, inclusivity, accessibility, anti-racism, and anti-casteism”, according to the government.

Dhaliwal says it will take more community activism to get things where they need to be.

“I believe the community is going to have to do what we’ve always done—take it upon ourselves to begin convening and having conversations, to build our own critical mass and raise a collective voice that will speak loudly enough for the ministry to finally pay attention,” he says. “Our community has a history of revolutionary, leaderless movements when we rise up together. Something similar is going to be needed here. Otherwise, we risk becoming the custodians of a compromised institution with watered-down narratives that don’t come close to capturing our stories or our world views. It will be too late to do anything at that point, because the government will have ticked that box on their checklist and moved on. Meanwhile, future generations will have these feeble stories and timid narratives upon which to weave their identities. Personally, I’d rather this project didn’t happen right now, than to happen in this way. At least then, the gap would be visible, rather than be filled with a counterfeit product sold to us as something genuine and meaningful.”

Establishing a new museum on the ancestral lands of B.C.’s First Nations represents an important opportunity to advance reconciliation, the government states. “This process will be accountable to the province’s commitments to reconciliation expressed in B.C.’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA), and not replicating colonial patterns during the engagement process or in the establishment of the museum,” reads the statement.

See https://engage.gov.bc.ca/southasiancanadianmuseum/ for more information.