Vancouver artist Ron Terada reframes real pandemic headlines on a grand scale, at the Polygon Gallery

He captures the wild ride of 2020 through 325 meticulous paintings, in the new exhibition From Slander’s Brand

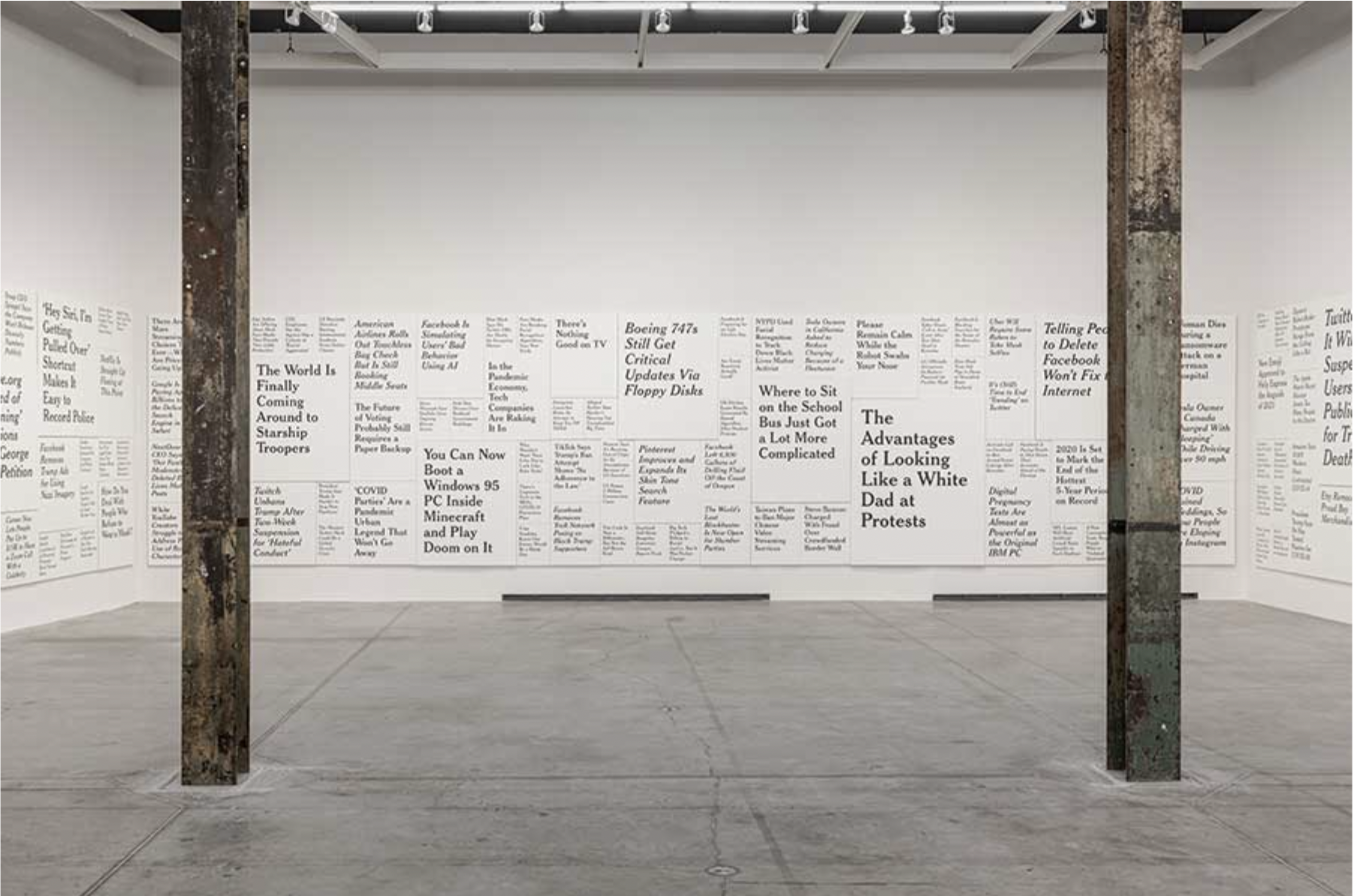

Ron Terada’s TL; DR (detail), shown in the exhibition From Slander’s Brand, at the Polygon Gallery.

From Slander’s Brand runs at the Polygon Gallery to February 4

AMID THE SEA OF news headlines that make up Vancouver artist Ron Terada’s monumental new frieze at the Polygon Gallery, words pop out that instantly take you back to 2020. Terms like “Superspreader”, “Nonessential Traffic”, “Contact Tracing”, and, yes, “Murder Hornets” and “Tiger King” (remember him?) feel not quite obsolete, but somehow distant, as if suspended in a fog of recent memory. Far away, so close.

In the new piece called TL;DR, pandemic lingo juxtaposes with tech names—“TikTok”, “Twitch”, “Google”, “Macbook”. That’s because Terada was sourcing real headlines from the American technology news website The Verge at the height of COVID lockdowns. And so “Twitter Labels Trump Tweets ‘Potentially Misleading’ For the First Time” shares the same wall space as “‘COVID Parties’ Are a Pandemic Urban Legend That Won’t Go Away”, along with the absurdity of “Please Remain Calm While the Robot Swabs Your Nose”.

“What attracted me to The Verge in the first place was that some of the headlines just didn't seem real to me,” the veteran artist explains, speaking to Stir in the days before the Polygon opening of the three-artist show titled From Slander's Brand. “They almost seemed like fake news. There’s something in the language of The Verge’s journalism that doesn't strike me as proper journalism. So it was important that it still had the look and the voice and authority of news.”

To achieve that, Terada has rendered The Verge’s often cheeky headlines not in their usual, punchy sans-serif font but in the instantly recognizable, serious serif of the New York Times.

“In fact, at one point, a friend and I, we actually tried to approach the New York Times to get their exact Cheltenham typeface—but of course, they wouldn’t give it up,” he reveals. “But, you know, it’s based on Cheltenham—so it definitely looks close enough that it will trigger in your mind that ‘Oh, this is the New York Times.’ But then again, you still have to deal with, as you’re reading it, it doesn’t read like the New York Times.”

Draw closer to TL;DR (internet slang for “too long; didn’t read”), and you’ll sense another level of incongruity. The carefully arranged headlines are actually painstakingly hand-painted across wall-length panels (using vinyl stencils, Terada says).

Organizing the 2020 headlines into these 325 large-scale works, which make up a continuous, 205-foot-long frieze at the Polygon, took the artist two years in his studio. And so this techy look back at the fleeting news scrolls of 2020 is actually realized in a permanent, slow medium that dates back to, well, cave walls.

“Painting is the oldest medium for communication, right?” says Terada. “It basically suspends things or holds things in time. Whereas you know how we eat or consume the news now: it’s just flip flip, flip, swipe, swipe, swipe. So you're constantly bombarded and you just keep scrolling. But painting is a way of sort of solidifying these absurd headlines stacked on top of each other—such that now you physically have to scroll through it as a viewer, to read the work, or encounter the work. So I wanted that kind of more bodily experience as opposed to some experience where you’re just swiping the screen.”

In the From Slander’s Brand exhibition, TL;DR shares gallery space with similarly work-intensive pieces by two other artists. Each of the three finds complex and innovative ways to capture and respond to a transformational, traumatic period in recent history.

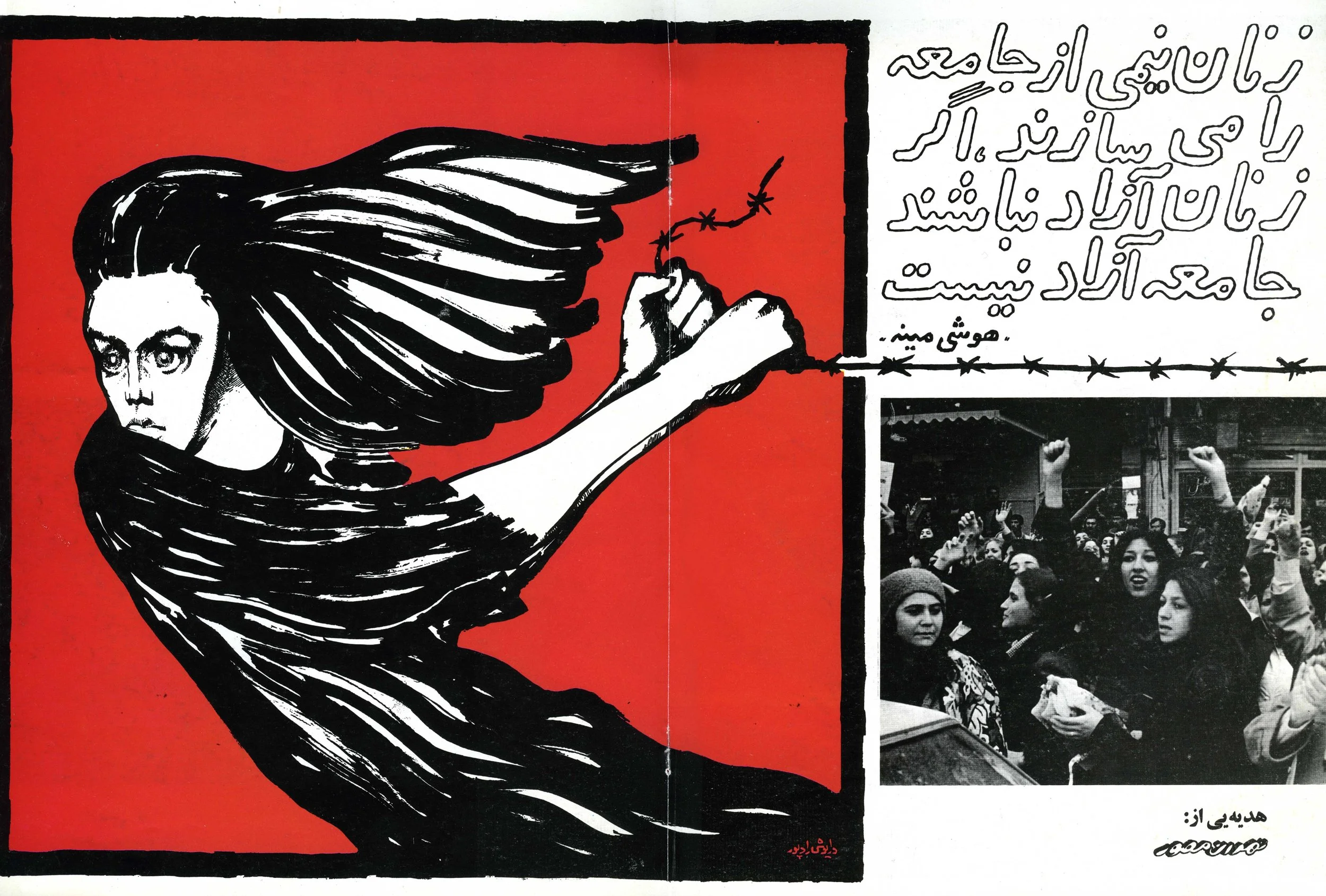

Paris-based artist Hannah Darabi’s Enghelab Street, A Revolution through Books: Iran 1979–1983 (2019) archives a variety of publications, including rarely seen photographic and propaganda books, that track the shift from free expression to religious dictatorship in her home country.

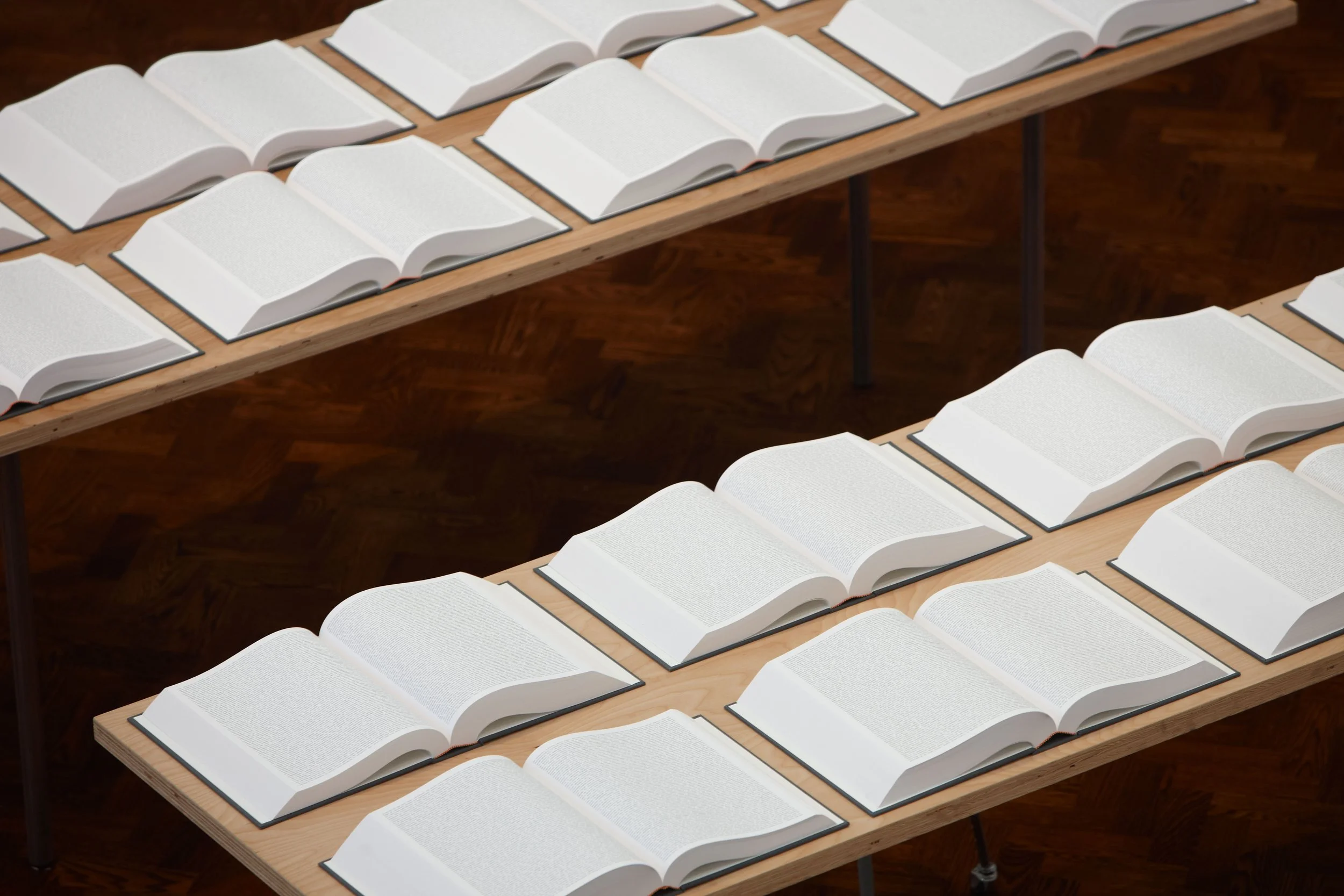

Like Terada, Australia-born, Zurich-based artist Rachel Khedoori looks to online news for inspiration for her work Untitled (Iraq Book Project) (2008–2010), an austere installation of 70 books that compile a chronology of articles found online using the search terms “Iraq”, “Iraqi”, or “Baghdad”. Translated into English and taking the form of a single, seamless line of text, it shows the way perceptions of the war shifted according to time and place.

Ron Terada’s TL;DR, 2020-2022, installation view from The Power Plant’s WE DID THIS TO OURSELVES, 2023. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy the artist and Catriona Jeffries

For Vancouver’s Terada, like the other artists, the work seems to be about trying to capture the complexity of a moment in time through a vast array of collected material.

“Instead of commemorating a singular event, I’m commemorating all the events that make up the year 2020,” he explains, “even the most frivolous and the most mundane and most, I guess, traumatic or heightened.”

Working with text is familiar territory for Terada, of course. Often drawing on popular culture, he’s reimagined phrases and idioms in a variety of media over the decades. His Border Divide, from 2005, was a roadside sign commissioned by the Windsor Art Gallery. Originally installed this side of the Michigan border, it read “YOU HAVE LEFT THE AMERICAN SECTOR” in English and French, in white on green. (It was soon officially removed and cut to pieces, but Terada re-created the work in black-on-white, with one of the signs at the National Gallery of Canada.) In 2003, he made clever use of neon to captured post-9/11 anxiety in Five Words in Coloured Neon. It glows with the stacked words “SEVERE, HIGH, ELEVATED, GUARDED, LOW”—drawn from the War on Terror’s threat advisory scale. And he applied acrylic on canvas to create his well-known “Jeopardy Painting” series in 1998 and ‘99—placing some of the TV trivia-game show’s clues (“ITS THE LAST NAME OF THE FAMILY HEADED BY CHEVY CHASE IN THE NATIONAL LAMPOON ‘VACATION’ FILMS”) in block letters against vibrant backgrounds.

The multiyear series TL;DR started in 2016 when he first conceived of putting the tech journal’s headlines into a more serious, painted font. Terada was ready to move onto something else when COVID stopped the world—and he realized he had a chance to zero in on a totally unique era of lockdown. Little did he know he’d also end up tracking everything from Black Lives Matter to Trump’s election follies.

Terada spent two years creating the 325 paintings on view at From Slander’s Brand—a meticulous process of compiling and editing down the uncountable headlines he’d collected, then re-creating them in acrylic on canvas. But for Terada, “It’s just work.”

“At a certain point you don’t actually think about it anymore,” he shrugs. “You’re just trying to forge ahead and make as much progress as you can every day. So there wasn’t much more to it than that. There’s no epiphanies or, you know, moments of transcendence.”

Through that labour, and out of a lot of misinformation, he might just have created something approaching the complicated “truth” of an era infamous for its misinformation. Still, TL;DR already holds vastly different meaning than it might have if we’d seen it in the dog days of 2020, when it didn’t seem like we’d ever leave the house again—or at least, unmasked. And yet it’s a somewhat scary reminder that the more things change the more they remain the same: have you checked Trump’s polls or COVID rates lately?

“I think it will look quite different 10 or 15 years from now, definitely,” the artist says of TL;DR. “So in some ways, as time keeps moving along, the work will become more and more of a time capsule of a particular moment.”

Rachel Khedoori’s Untitled (Iraq Book Project) (2008–2010, detail)

Hannah Darabi’s Enghelab Street, A Revolution through Books: Iran 1979–1983 (2019, detail)