Leif Garrett, Black Sabbath, and upside-down Christmas trees: Steven Shearer mines archived imagery for a deeply layered viewing experience

New exhibition at the Polygon Gallery speaks directly, and sometimes painfully, to growing up in the 1970s

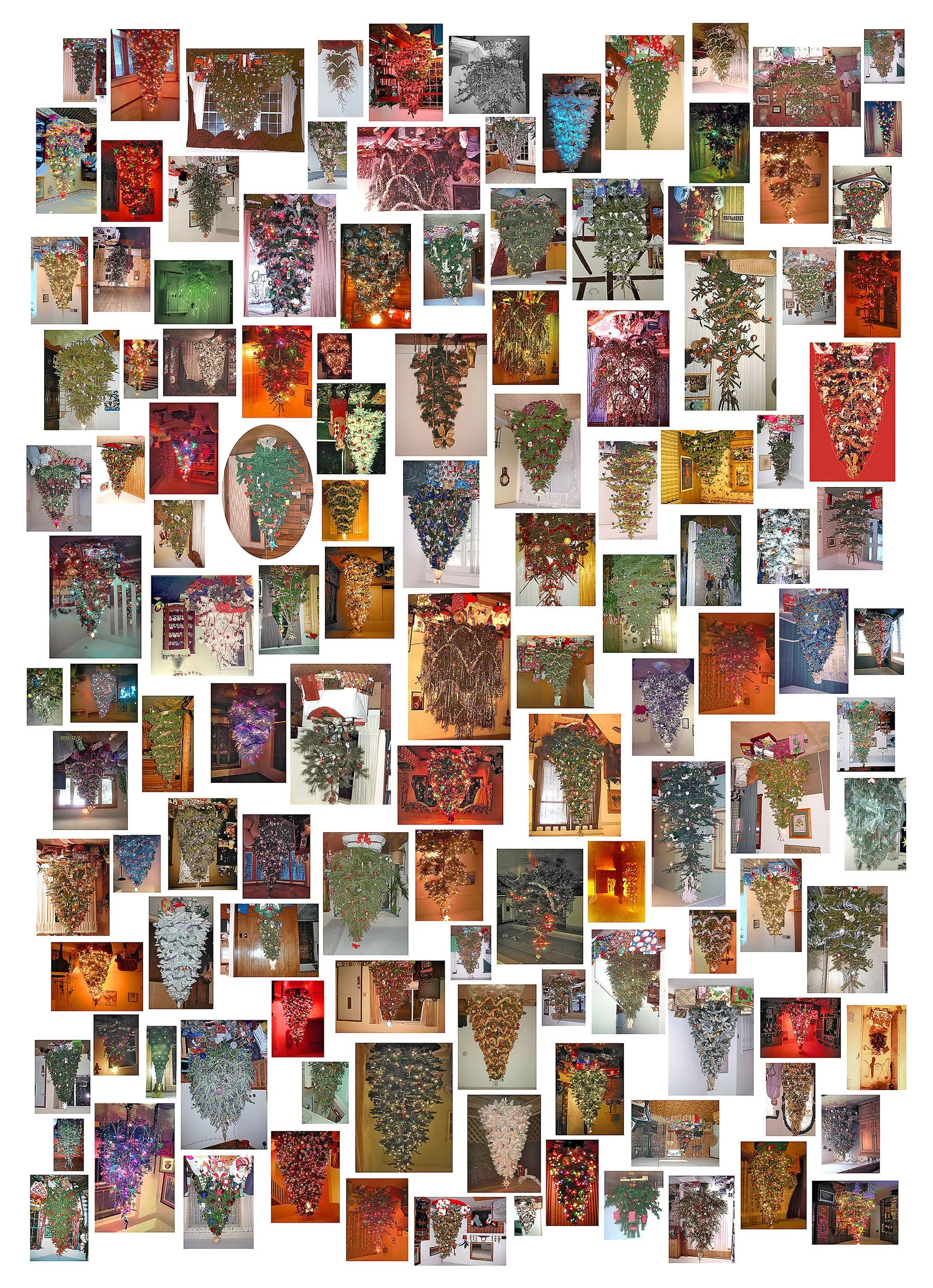

Xmas Trees, 2005, © Steven Shearer.Courtesy Private Collection

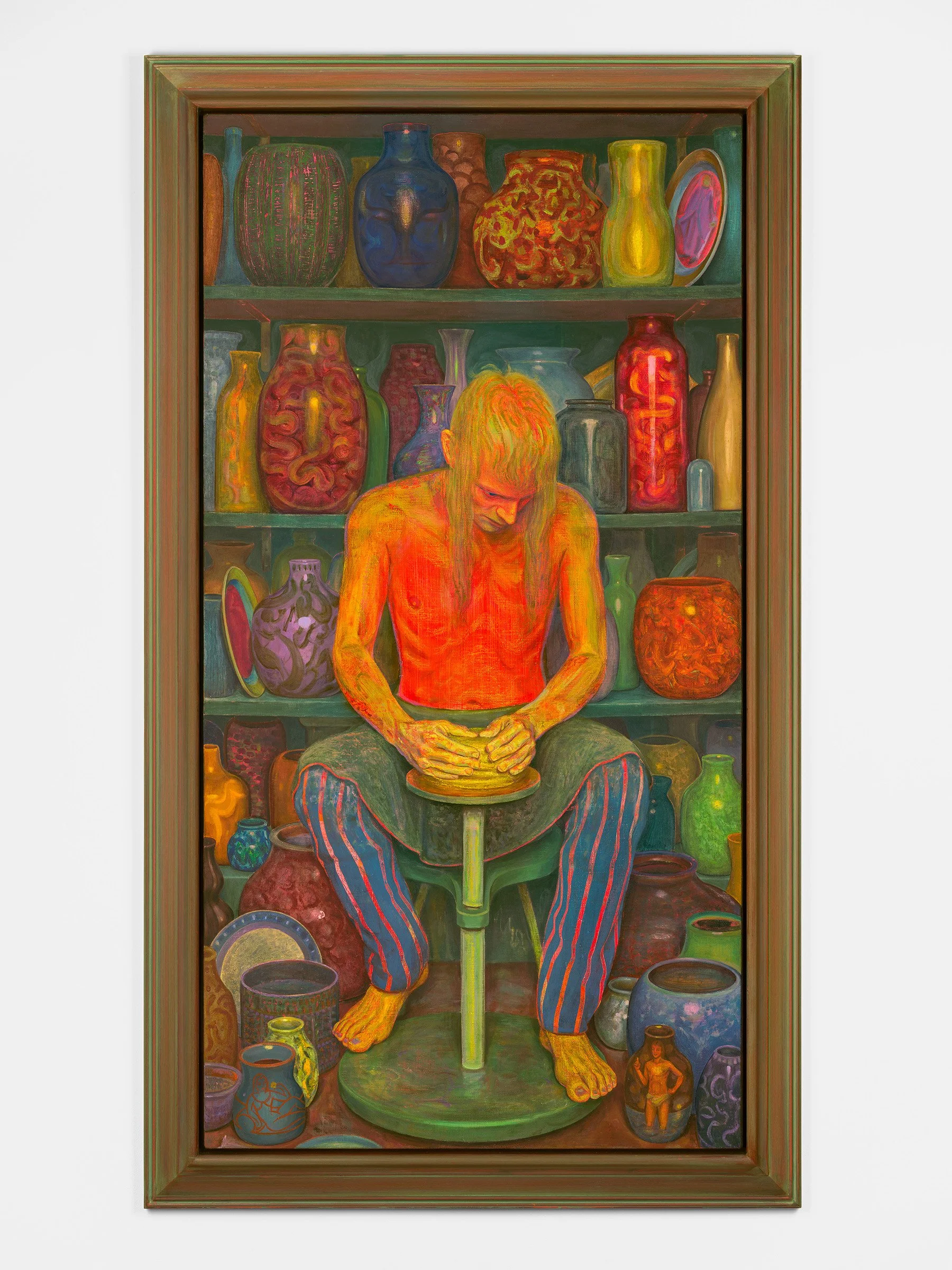

Potter, 2021 © Steven Shearer. Courtesy The George Economou Collection, Athens, Greece.

The Polygon Gallery presents Steven Shearer to February 13;

FOR ANYONE WHO grew up in the era of Shaun Cassidy posters, Black Sabbath 8-tracks, and wood-panelled rec rooms, Steven Shearer’s vast and absorbing new solo show at the Polygon Gallery feels familiar in ways that may make you wince.

Over the course of his career, the Vancouver artist has famously accumulated an archive of more than 78,000 found photographic images—many of them scooped directly from the experience of suburban 1970s male adolescence.

Shearer—celebrated in Europe but rarely shown here—reassembles and filters those images in multiple ways. The exhibition, called Steven Shearer, spans collage, painting, drawing, and sculpture, all inspired, in some way, by his scavenged photographs. In Clifford, he uses a crayon and paper to sketch a portrait of a young metalhead, whose long hair flows frizzily over his shoulders, with the love of a Rembrandt. In Metal Archive (study), he arranges shots of ‘70s speakers, garage drum sets, Black Sabbath T-shirts, and Flying Vs into an intricate polyptych. With the care of an anthropologist, Shearer chronicles the rise of androgynous teen heartthrob Garrett in not one but two giant volumes of his Artist books.

For a certain generation, these touchstones cause a weird flood of nostalgia and pain, sparking the kind of laugh that catches in your throat. As Polygon director Reid Shier puts it in a press tour, “There’s an uneasy quality to a lot of Steven Shearer’s work that really pushes us to a place that’s uncomfortable.”

What does it all mean? That’s up for interpretation. But Shier is clear about what it does not mean: “It’s not irony. I would never call Steven’s work ironic.” Instead, he sees Shearer’s work as deeply empathetic, as “questioning the value we put on things”, whether that’s a dog-eared Teen Beat, a blurry snapshot of a family Christmas tree, or a Renaissance painting.

Shearer, born in New West in 1968, is as obsessed with art history, from Renaissance masters to Edvard Munch, as he is with ‘70s teen culture. And that’s a hint that his work has much more to say than scrapbooking a past era.

As a Boy, 2006 © Steven Shearer

Clifford, 2006 © Steven Shearer

He made headlines in Vancouver last spring for a series of billboards he created for the Capture Photography Festival from shots, gleaned from the internet, of people napping. Sponsor Pattison Outdoor Advertising removed them due to public complaints. The masses mistook them as something more sinister and deathlike, distasteful in an era of opiate overdoses. Though not shown here, they hint at Shearer’s ongoing interest in the infinite archive of imagery that lives on the interweb—of ideas of watching and looking. They also refer to historical paintings of subjects in repose. And, like so much of his work, they unsettle in interesting ways.

The exhibit’s Xmas Trees finds the artist taking the everyday images we collect and turning them literally on their head: in the Inkjet print, he’s assembled 150-odd photos of upside-down Christmas trees into what looks, from the distance, like an abstract grid pattern. Get up close and you’ll feel a pang of recognition for the kitschy ornaments and heaped tinsel, documented in blurry, bad light, sitting in wood-panelled basements or in front of gaudy drapes. It’s anonymous yet era-specific, absurd and ominous as they point downwards.

Sideshow Rigmarole (detail), 2020. © Steven Shearer. Courtesy of Galerie Eva Presenhuber, and David Zwirner Gallery

Sprawling across an entire wall, Sideshow Rigamarole features images culled from the ‘60s and ‘70s, photo-laminated in the neon hues of sticky notes. Some of the shots feature celebrities—David Cassidy brushing his teeth in a mirror, Alice Cooper emerging from a pool—and others picture boys and men posing with cannons, cats, and skeletons, cavorting with crutches, or mimicking album covers. Together they form a survey of masculinity and manhood, filtered through the lens of pop culture.

“They sit on this slippery edge of memory and recollection,” Shier reflects. “He’s interested in these things that we can’t quite place.”

Shearer rarely takes photos himself. The exception here is the curiously unsettling Bat Post-It Statue—a triptych of Inkjet prints that features a homemade Batman piñata and one of those creepy Italianate statues that used to sit along Great Northern Way, vandalized to look like a sad clown. Between them? A sketch of Garrett on a Post-It note. “He’s not afraid to show us his doodles,” Shier comments.

Perhaps the most surprising piece is the gigantic sound-sculpture cube that sits at the centre of the exhibition, Geometric Mechanotherapy Cell for Harmonic Alignment of Movements and Relations. Reproduced from an archival image of a play structure and forged out of black PVC sewer pipe, it heaves and groans—vibrations that feel part bass guitar, part primeval force summoning the masses.

The biggest draw, and possibly the most self-reflective work in the exhibition, is the mesmerizing Potter—a strange and luminous painting that pictures a stringy-haired, bare-chested ceramicist hunched over his potter’s wheel. The shelves behind him are weighed down with the vessels he’s created. As much as the work fits into a long art-historical tradition of paintings about an artist and his practice, Potter reveals mysteries on closer viewing. As Shier points out, the red-glowing squiggles of the hair on the figure’s head look almost cranial; his skinny torso, too, radiates red with intensity. While some of the pots seem opaque, others appear to hold bloodied intestines.

It says something that this monumental painting sits on the same wall as the upside-down Christmas trees, a rough photocopy of an anonymous adolescent set in a cheap acrylic block frame, and a pencil drawing of a mulleted, mustached dude as a formal portrait bust—think Fubar’s Dean Murdoch as highbrow hero.

Random forces—headbangers, PVC pipe, Post-Its—fit together easily with classical touchstones in Shearer’s sprawling world. And that helps explain the odd, ambiguous feelings this unnerving and engrossing new show ignites.

More than anything, this is work that invites in-person close inspection--a rarity in a pandemic era. Whether it’s Potter’s intense, surreal world, or Metal Archives’ tiny array of banger souvenirs, Shearer’s work reveals its nuances through looking, reflection, and remembering. “You have to be with it and actually see it,” says Shier. “Steven is an artist who really rewards optics.” Even if it makes you wince.

At the Polygon Gallery, Geometric Mechanotherapy Cell for Harmonic Alignment of Movements and Relations and Sideshow Rigamarole .