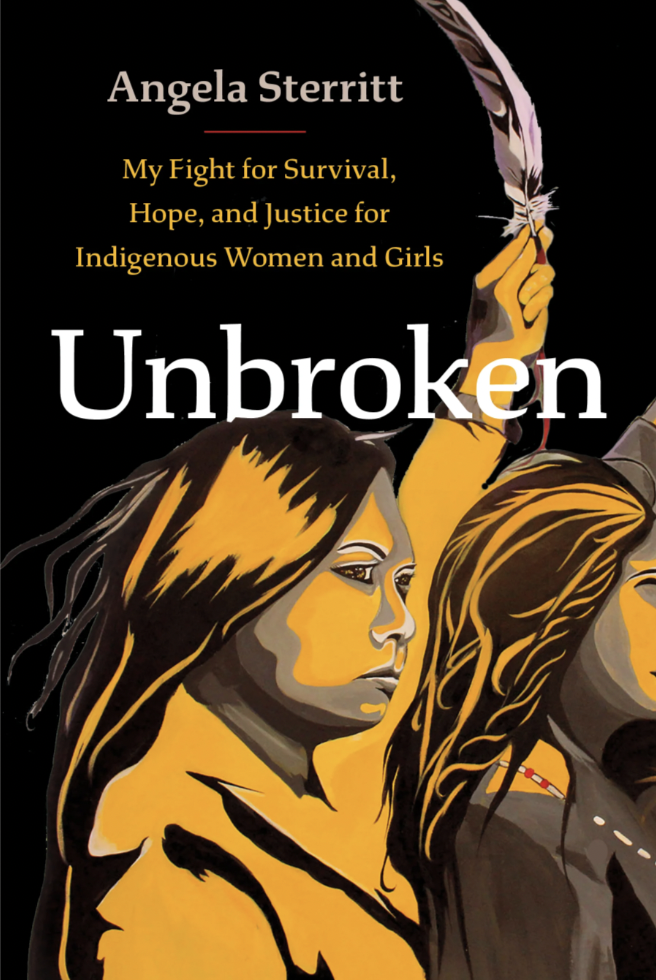

Stir Q&A: Vancouver-based Gitxsan journalist Angela Sterritt discusses her new book, Unbroken

Subtitled My Fight for Survival, Hope, and Justice for Indigenous Women and Girls, the forthcoming title is a gripping read

Angela Sterritt. Photo by Farah Nosh

LOCAL GITXSAN JOURNALIST Angela Sterritt’s debut book, Unbroken: My Fight for Survival, Hope, and Justice for Indigenous Women and Girls (Greystone Books), opens with the names of Indigenous women and girls who were murdered or have gone missing along B.C.’s Highway of Tears and adjoining highways and from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. It is a gutting acknowledgment of 142 precious lives lost. There are likely more that Sterritt was unable to find or confirm. Any one of those names could have been hers.

The daily-news and investigative journalist at CBC spent years writing the book, which comes out later this month. A densely researched and gripping read, it weaves together factual details of cases of B.C.’s missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls with interviews with family members—their stories touching on the lack of urgency and care from police and government authorities toward the people they loved so deeply. Also interspersed throughout are personal details about Sterritt’s own background, including her time as a teen and young adult homeless and hitchhiking across Canada and the United States. She was barely 14 when her dad told her to make arrangements for foster care or to grab a sleeping bag and find somewhere to live on the street; there was no place for her in the former system, so out to downtown Vancouver she went.

Unbroken also takes a critical eye to Forsaken: The Report of the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry (the Pickton inquiry) and to the subsequent National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, and how both not only failed families but also retraumatized them. Equally scathing is Sterritt’s account of the media’s bias, racism, insensitivity, and lack of understanding when it comes to Indigenous stories, with some CBC producers in the past describing many of Sterritt’s story pitches as “advocacy journalism”.

In addition to working at CBC, Sterritt has started research for her next book and is travelling the world to learn about different healing modalities. Stir connected with Sterritt in advance of Unbroken’s upcoming release.

How did you go about taking care of the emotional and mental well-being of the people you interviewed for Unbroken—as well as your own?

For the family members of missing and murdered Indigenous women, I check in with them often. This book was different than daily news in that it took more than five years to write, so I was talking to them for, in some cases, hours at a time. Most of the family members were in good places, but there was one man I spoke to who was not. We decided not to name him in the book, as I was mindful of the trauma the interviews could cause him. I listened to his concerns and ultimately decided not to publish information about his family despite a public interest. I also made sure he had family or friends or other supports before, during, and after our interviews.

Being trauma-informed often means taking the lead from people who are in trauma, letting them ask you questions, collaborating with them when it comes to telling their story, and making sure they are in a good place to share.

I do many practices with healing modalities that calm my nervous system, from meditation to exercise to being on the land to being among friends and kin. I am also a deeply spiritual person and rely heavily on my ancestors for guidance and assistance.

Some people say that writing about trauma can be healing or cathartic. How would you describe the years-long process of writing the book and its impact on your life and work?

The first few years were really difficult. I was delving into trauma that I was really not ready to delve into. I didn’t have a lot of internal or external resources. But in 2018, after a traumatic event, I began to understand trauma and was paired with a coach who helped me to get strong and soft. Then in 2022, two other significant traumatic events happened that sort of shook me to delve even deeper into self-care and self-love. I feel I am stronger and more open-hearted than I have ever been in my life and feel so excited to share my story to fulfill my life’s purpose which is to help others feel seen through sharing their truth, and ultimately help them heal.

This is a story that continues to unfold. How did you determine when it was time to put the pen down?

I didn't! I am writing book 2 now which is sort of a part 2 to Unbroken. But honestly, my editor Jennifer Croll carried my book in tremendous ways to make it what it is today. Without her, the whole Greystone team, and my agent Samantha Haywood, my book would most likely never be completed.

You have always felt a pull to journalism and storytelling and have said you feel a responsibility to do Indigenous people and communities justice with your work. Can you share more about this?

My parents used to come into my daycare when I was, like, three and see me holding a book upside down and “reading” to a gaggle of kids. I believe it is in my blood to story-tell, and it is a gift that I have been honoured to carry that comes with great responsibility. What motivates me is seeing Indigenous people being uplifted through the stories I share, their truth being believed, their stories being told with all the integrity they deserve, and of course seeing conversations started, sometimes internationally, as a result of my stories, that have resulted in great cultural and policy shifts.

How have things changed in the media industry, in your experience, since you began writing the book in 2015? What still needs to happen in newsrooms when it comes to Indigenous stories being treated with the same respect and urgency as non-Indigenous stories?

Metrics on stories (which share, for example, how many people are reading a story) and social media have played a huge role in demonstrating the importance of Indigenous stories, so that has compelled, in many ways, journalists to pitch more Indigenous stories and see that these can be top stories, not stories that were pushed to the end of a newscast or put low on a website. However, when it comes to missing Indigenous women and girls, there are still a lot of deficits in the way we cover them. Indigenous women, girls, or two-spirit people who are missing may not be covered by the media until there is suspicion around it or unless the family members are calling on the police or the media to act on it. Yet a white woman who is missing will, in contrast, have satellite trucks and tonnes of police resources on it. I talk about this in my book. There is often still more reliance on police accounts of the cases rather than the family members, even when the family members may have ample evidence as to how she went missing. There is also still, in some cases, a lack of education about Indigenous issues and people in general. I always think it's telling when I may be the only Indigenous person that a journalist knows. Relationship-building needs to go beyond a professional setting in order for people to have a deeper level of understanding of colonial violence and the systemic change needed.

In terms of racism in institutions like newsrooms, in-person, group and individual training can be useful, but consequences that demonstrate that racism is not tolerated and not part of the culture are necessary.

What is your hope for the book once it is out in the world?

I will just say that I hope this book sheds light on the reality that a genocide happened in Canada, and policies and cultural norms today maintain colonial violence and white supremacy and create a world that Indigenous people are not safe in. But I also hope it shines a light on the brilliance and strength of Indigenous people, and our tenacity to not give up until we see justice for missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people.