Filmmaker Atom Egoyan reflects on The Sweet Hereafter, bringing new restoration to The Cinematheque

The celebrated Canadian director recalls the snowy BC shoot, the haunting performances, and the most indelible scenes

Atom Egoyan was inspired to shoot the film in BC after a family vacation driving through the Interior.

The story of a doomed schoolbus was shot in and around Merritt and Spences Bridge.

The Cinematheque presents The Sweet Hereafter (An Evening With Atom Egoyan) on March 30 at 7 pm

It is arguably the most indelible image in 1997’s The Sweet Hereafter—a movie so packed with haunting scenes that it is regularly named one of the top 10 Canadian films ever made.

A tiny toddler lies on her father’s lap on a tense ride from a remote cabin to a hospital. A poisonous spider has bitten her, and her parent keeps her still, all while holding a gleaming jacknife by her throat in case she stops breathing and he has to perform an emergency tracheotomy. The darkly parabolic sequence is full of innocence and horror, symbolizing the lengths a parent will go to save a child. And the look on the child’s face captures all of that: a hard, unwavering stare that’s stern and unsettling in ways that defy her years and her angelic blonde curls.

“The child in the car was a daughter of a really good friend,” Egoyan recalls with a laugh that reveals he’s been asked about the scene many times. He’s speaking to Stir from his Toronto studio before heading West to host a screening that celebrates a new restoration of The Sweet Hereafter. “What she was summoning, I don’t really know. I just said, ‘Look into the lens.’ And there was something about that look that is so unbelievable. And she held it for so long! That was just one of those miraculous shots.”

A lot of magic seemed to come together on the shoot for the melancholy story about a snowy schoolbus accident, its devastating effects on a small town, and the big-city lawyer who arrives to launch a class-action suit. There was the way the film transformed dramatically in the editing process into a powerful, nonlinear meditation. And the way Egoyan was inspired to build it around a metaphorical Pied Piper storybook.

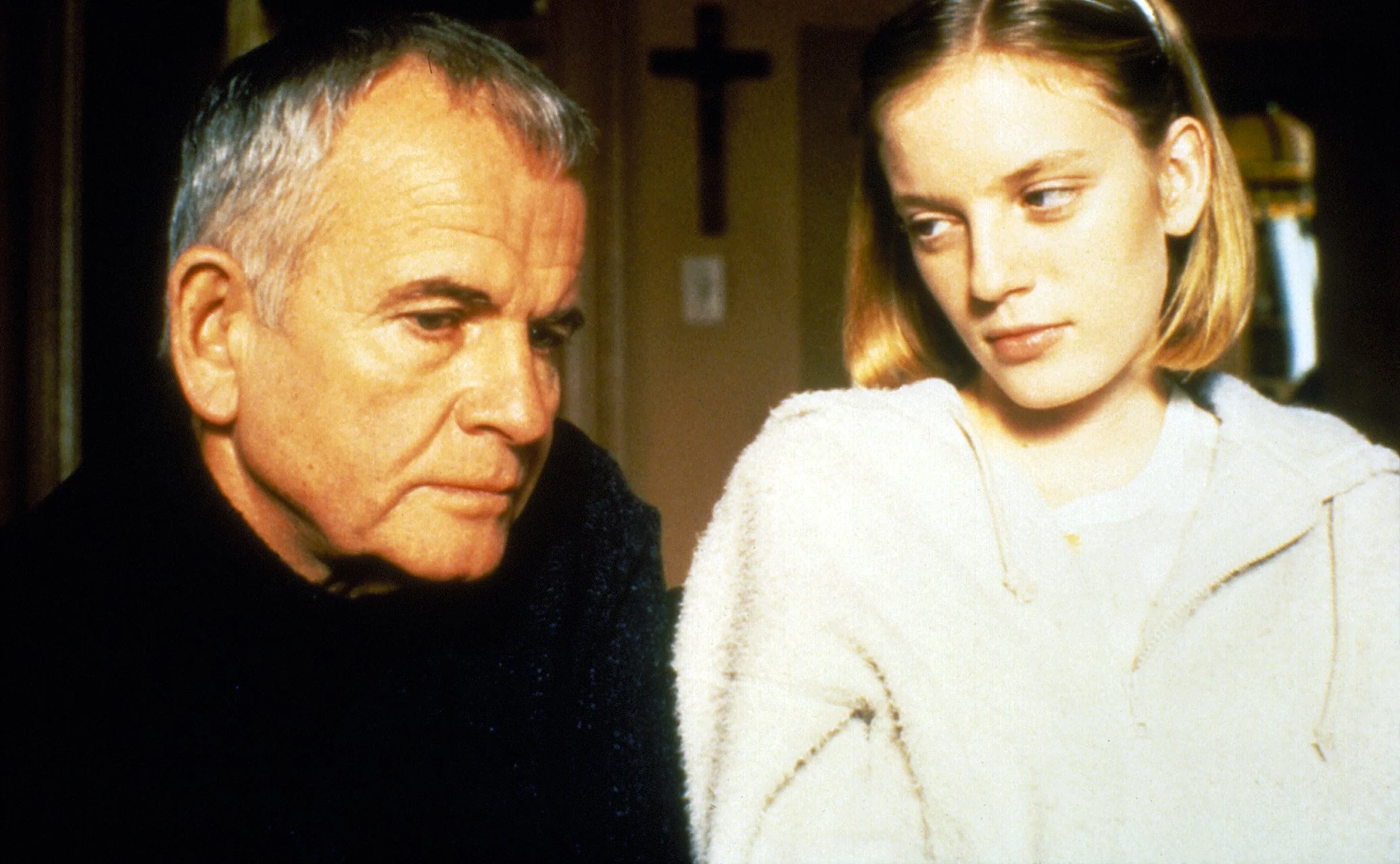

When Egoyan looks at the film now, though, one of the most “miraculous” elements is the ensemble cast that includes Sarah Polley, Ian Holm, Gabrielle Rose, Bruce Greenwood, Maury Chaykin, Tom McCamus, and Earl Pastko.

“There were the Academy Award nominations and the prizes in Cannes, but what was really meaningful was the best ensemble award from the National Board of Review—to have the whole cast recognized,” the director says. “I just see it as the cream of Canadian actors, and we were fortunate to get this British actor [Holm] who they regarded as a god—but who was able to just blend into that ensemble.”

The striking performances are just some of the reasons why The Sweet Hereafter is being revisited this week as part of the Cinematheque series The Image Before Us: A History of Film in British Columbia, curated by film instructor Harry Killas.The links to this province include not only the fact that Egyptian-born Egoyan was raised in Victoria, but that its elliptical story, adapted from author Russell Banks’s novel of the same name, was shot largely around Merritt and Spences Bridge.

Egoyan was inspired to move the locale from the book’s Upstate New York setting not from experiences visiting the Nicola Valley area growing up, but from a trip when he was older, with his own family. He and wife Arsinée Khanjian (who also stars in The Sweet Hereafter) and son Arshile had flown into Calgary and then drove through B.C.’s Interior on the way to Vancouver and Victoria.

“I was showing my wife and son the Rockies, but they’re too monumental and don’t fit in the frame,” he relates. “But there was something about arriving in the Okanagan and going through the Nicola Valley where the landscape fit into my visual scale, even though onscreen the mountains there feel quite monumental.”

Though most of the interior scenes are sets, he was able to find some wonderfully woody locations, including Spences Bridge’s retro Baits Motel (the “Bide-A-While Motel” in the film) and an A-frame “hippie house”. The director reveals that the shoot narrowly missed a massive snowstorm that would have shut down production.

If the setting gave the film a distinct look, so did the way it was shot. Another of its unforgettable sequences is the central bus crash itself, which comes late in the film—and which is shot at a distance instead of in multiple, action-movie closeups.

Egoyan reveals he wanted to shoot it that way to allow the audience to feel the helplessness of Bruce Greenwood’s character, Billy. The local garage owner happens to be following the bus in his pickup that day—his twins waving to him from the back of the vehicle.

“The ice cracking really surrounds you in the surround sound in the theatre,” Egoyan says, “and just to see his figure stand in a way that he's realizing he's never going to make it in time. If you were making this as a Hollywood movie you’d never be able to shoot it in that way. The convention would be that you’d be closer to the bus or seeing the kids.”

A video still from the film-opera hybrid Bluebeard’s Castle.

TAKING RISKS AND bucking conventions helped define a golden age of Canadian indie filmmaking in the 1980s and ‘90s. Called New Canadian Cinema or the Toronto New Wave, it featured brilliantly offbeat, genre-busting films by auteurs like Egoyan and his colleagues Bruce McDonald, Don McKellar, and Peter Mettler.

Long after The Sweet Hereafter, of course, Egoyan has continued to direct films—including 2009’s Chloe with Amanda Seyfried, 2015’s Remember with Christopher Plummer, and 2019’s Guest of Honour with David Thewlis. Dating back to the mid-1990s, he has also made a name in the world of opera, directing dark works like Richard Strauss’s Salome for the Canadian Opera Company and Vancouver Opera.

Interestingly, his two loves–cinema and opera–have come together this year in a highly recommended new rendition of Bela Bartok’s dark Bluebeard’s Castle, viewable for free on the Canadian Opera Company site. In the online production, Egoyan brilliantly weaves his film Felicia’s Journey, made just two years after The Sweet Hereafter, into the opera itself. Shot with tense, Hitchcockian style, the film tells the story of a disarmingly polite serial killer (Bob Hoskins) who preys upon a young, pregnant Irish woman who’s arrived in Birmingham to find the factory-working father of her unborn child.

Egoyan says he had the story of Bluebeard’s Castle in his head as he wrote it. The virtual opera opens with the titular character watching the first 14 minutes of the film on his laptop. Then, with the movie continuing on a projected screen above the action, we watch the story of Judith, who comes to live with the brooding recluse Bluebeard. In the original, he forbids her from looking at the horrors behind seven closed doors; in Egoyan’s chillingly reimagined new version, computer USB sticks replace the seven “keys” of the original. Props that refer back to the film onscreen appear eerily onstage. (Available for streaming worldwide at www.coc.ca/Bluebeard through September, it stars Vancouver stage favourite Krisztina Szabó with Kyle Ketelsen as Bluebeard.)

In Egoyan’s hybrid reimagining, Judith takes on a more active role in her fate.

“It’s a very problematic story to tell right now,” Egoyan relates. “If you follow the story literally it's really a story of a woman who sublimates herself to a man. It’s a very dark story and I wanted to give it a different take where the female character will have some agency.”

Those themes of trauma and a woman finding her agency link that bold new work back to much of Egoyan’s cinematic oeuvre—and, interestingly, to The Sweet Hereafter itself. The then-teenage Sarah Polley’s role in the film has come under scrutiny lately, after revelations in her engrossing new memoir, Run Towards the Danger. In the book, Polley reveals her struggles as a child actor, demands on her to act like an adult, and several complex parallels between the life of her character Nicole and her own experiences. The film’s key moment involves Nicole standing up against what’s been happening to her.

“That’s another change from the book,” Egoyan begins, addressing one of the most discussed moments in any of his films. “I had worked with Sarah in [1994’s] Exotica and was just so aware of what an exceptional actor she is. And so when I was writing Nicole, I was able to have her in mind.

Ian Holm and Sarah Polley in The Sweet Hereafter, a film its director remembers most for its strong ensemble cast.

“I think she delivers something quite, quite, quite unique here,” he explains. “We’ve seen victims of abuse before, but it’s very unusual to show them in that moment before they understand how they’ve been victimized, before they understand the violence that’s been done to them. She's still in this space where she’s trying to understand what the father’s feelings are.

“I think what’s amazing about her performance,” Egoyan continues, “is that we understand her growing realization of how she’s been victimized, but also understand the resilience and her ability to reconstruct her own way of seeking justice. That is something you can write, but if you don't have the actress to deliver that it doesn’t work. And it's interesting reading her book now: there’s so much going on in her life that I didn’t know about in detail. And now I understand why it’s so clear—the ferocious clarity of that performance is coming from a lot of things in her life that just happen to conjoin themselves into the script.”

That performance alone makes The Sweet Hereafter worth another look at The Cinematheque this week. But mostly, viewers may be struck by how much the film seems to speak to pandemic times–the way we are before a trauma, and the way we are left to grapple with it in the hereafter.

Egoyan, for his part, hopes those ideas do not play out in an abstract way, but in a deeply personal one.

“We have to force ourselves to think of the stories of what individual families have been through,” he says, addressing both the film and the pandemic. “These are individual stories of people who weren’t able to say goodbye to loved ones. As a dramatist you really try to remind yourself of that—not the collective grief, but to really feel these stories on an individual level is what good drama is. It’s really too easy to abstract things.”