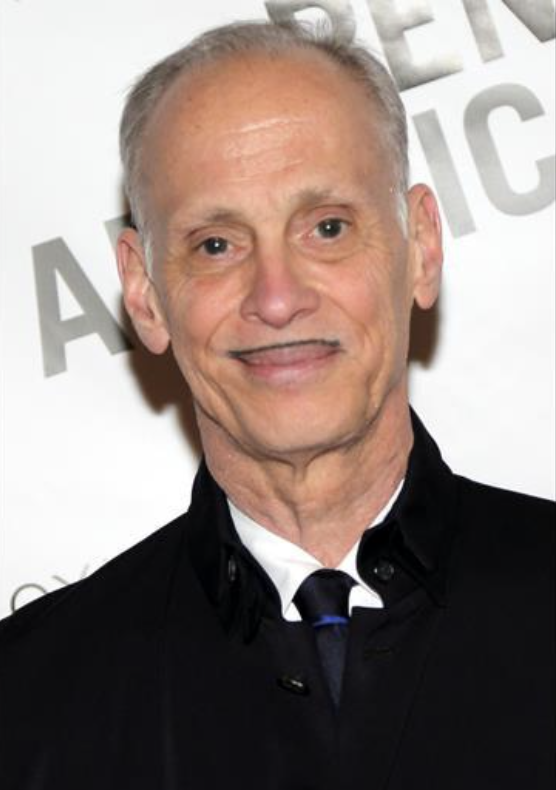

John Waters brings his outsider comedy to the Rio Theatre with two nights of film and spoken word

The countercultural icon of fringe cinema riffs on the dangers of smoking, mainstream acceptance, and trigger warnings in advance of his appearances at the Rio Theatre on April 25 and 26

Ricki Lake, Johnny Depp, and Traci Lords in 1990’s Cry-Baby.

The Rio Theatre presents John Waters LIVE! With Cry-Baby on April 25 at 8 pm and John Waters: Devil’s Advocate on April 26 at 8 pm

THERE’S ONLY ONE thing in life John Waters wishes he hadn’t done. “Smoke cigarettes,” he tells Stir, reached at his home in Baltimore prior to hitting the road for two nights at Vancouver’s Rio Theatre. “We didn’t know when we were young. They used to say, ‘Doctors recommend Kools when you have a cold.’ A lot of my friends are dead from smoking cigarettes or have cancer right now. Don’t smoke!”

Okay, but that’s pretty rich coming from the guy who was seen hauling on a menthol and goading patrons about the smoke-free environment in an infamous Public Service Announcement he made for Landmark Theatres in 1982. “Well, I mean, that is ludicrous, it makes my throat hurt even seeing me inhale like that,” he laughs. “That’s from a different time but it’s still funny, I think. Every once in a while I walk into a theatre and they’re still playing it, and I sink down to my seat hoping that people didn’t think I said, ‘Oh, I’m coming to the movies, put that on!’”

It was a different time, shortly after the Pope of Trash upped the filmmaking ante with Polyester (1981), putting his muse Divine in a Sirkian romantic clutch with queer icon Tab Hunter, and during his unlikely acceptance by the mainstream as an endearing figure. Waters was the man who pioneered human-canine coprophagia with 1972’s Pink Flamingos—true!—but he was also emerging as a charming public presence who occupied a unique position somewhere between raunchy and lovable. His breakthrough feature Hairspray cemented Waters as a cultural force in 1988, and we’ve been living in his screwy world ever since. If you wanted to see Female Trouble (1974) in the early ‘80s, you rented a tape and hid it under your jacket. Now your kids can watch the utterly insane Multiple Maniacs (1970) on Tubi.

"Would you wanna watch Multiple Maniacs with your 17-year-old daughter?” Waters asks. “I wouldn’t! The whole point of my movies was, ‘Suppose my parents saw this!’ Today people tell me, ‘My parents showed me Pink Flamingos when I was 14,’ and I say, ‘They should be in jail!’ That’s unbelievable to me. But they all seem to turn out fine. They’re the ones that come to my shows. The ones that were traumatized and became school shooters—they don’t come. But I don’t think my films have been a bad influence on anybody, I think they’ve been a good influence.”

The truth is that, in its earliest days, the implication within the John Waters cinematic universe was that conservative America in the ’50s was absolutely to blame for counterculture America in the ’60s. As he puts it: “LIFE magazine corrupted me. They wrote about the Beatniks, and they wrote about gay people, and then they wrote about LSD—so I was a corrupted by LIFE magazine, otherwise I would have never known these things existed in suburban Baltimore.”

Further to that, the perversities of his early underground films, like Desperate Living (1977), were still built on a moral framework and a clear affection for family, criminal or otherwise. “Yeah, true!” he says. “And the right people win. The people that lose are judgemental, and don’t mind their own business, and are jealous of other people’s success. And the people that win take what society uses against them, exaggerate it, turn it into style—and that’s what all my movies are about.”

For his first appearance at the Rio, on April 25, Waters presents Cry-Baby, an attempt at a PG-rated musical that tanked when it was released in 1990. About to get a shiny 4K re-release through Kino Lorber, his first real Hollywood film has a different aura almost a quarter century later. “It was when Johnny Depp was a teen idol, like Justin Bieber or something,” Waters explains. “It came out hugely widely released, but the teen audience had never seen an Elvis movie, they didn’t know it was a parody. Today, it’s a very loved movie. That’s what happens sometimes. God, so many people tell me that it saved their life when they were a kid—they saw it and they felt good about themselves. It’s strange.”

Waters’s adventures in Hollywood continued with the 1994 hit Serial Mom, and a string of features that ended with A Dirty Shame in 2004. Mirroring his onscreen worldview, it sounds like a John Waters set was a warm and familial place, whether he was working with his troupe of freaknik Dreamlanders like Mink Stole and Divine, or bringing Hollywood normies to Baltimore.

“I got along with every person I ever worked with, and I’m friends with most all of them still,” he says. “A movie star doesn’t read for you but they have a, quote, meeting, and if they ever use the word ‘journey’—that’s always a bad sign. I can just tell if they’re humour impaired. That happens subconsciously at the meeting. Susan Tyrell was drunk for the whole of Cry-Baby, so that was a problem, but we got along and she gave a good performance. People said, ‘You’re gonna have trouble with Kathleen Turner…’ but she wasn’t one bit difficult! I don’t think any of the stars I ever worked with would say anything bad about me.”

In recent weeks, film nerds have been lamenting that giants like Waters, David Lynch, and Francis Ford Coppola can’t secure financing or distribution for their new work. In his case, Waters has simply leaned on his other pursuits—“I am a writer. That’s how I make my living”—but the last decade has brought another cultural shift that has seemingly re-energized the People’s Pervert. For his second night at the Rio, on April 26, Waters presents his Devil’s Advocate spoken-word show, wherein he lampoons an entirely new kind of Moral Majority. It’s an incredible third-act feat; where progressives once embraced him, this bone-deep free-speech absolutist now finds himself at odds with an increasingly censorious left. In other words, he’s on the fringe again.

“We rioted for free speech,” he says, “and now on college campuses, ‘You’re not allowed to say that!’ A trigger warning is something that really made me laugh when I first heard it, ’cause I thought that’s why you went to college, was to get your values challenged. They’ve become humour-impaired. Self-righteous. That’s the difference. We used humour as terrorism when I was young. The Yippies did that. Today, I think you should be allowed to say anything. I’m for being allowed to yell ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theatre. We have to put up with the extremes. You have to put up with the good and bad to be free, and learn to be a curator in your life about what you look at, what you like, what you spread. And that’s all through humour. That’s why I’ve been able to last over 50 years doing this. Because I make fun of myself. And I make fun of the rules that supposed outsiders live by. There’s more rules today in the outsider community than my parents had in the ’50s!”

Naturally, he adds: “But I find that funny too.” ![]()