Film review: Dalíland captures the late-career circus that surrounded the surrealist

Ben Kingsley hands in a compelling performance in a film that emphasizes the party over the person

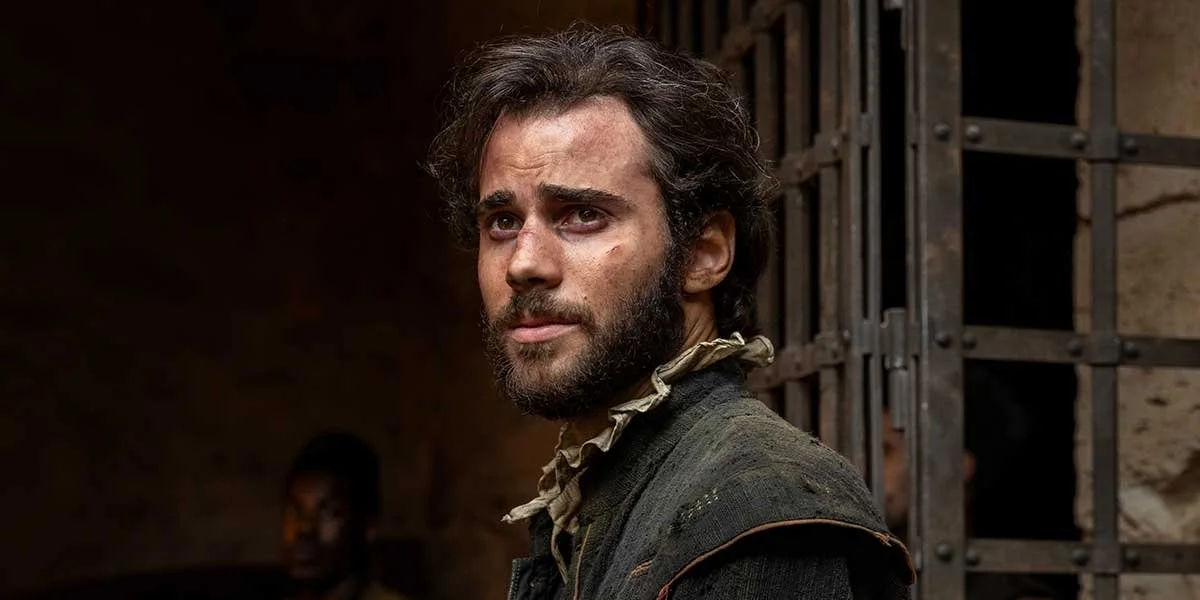

Ben Kingsley’s Dalí turns his moustache into an artwork all its own in Dalíland.

Dalíland runs at VIFF Centre to June 17

DALILAND OPENS promisingly, with Salvador Dalí’s infamous appearance on the 1950s quiz show What’s My Line?, the blindfolded panellists trying to guess who the mystery guest is. “Would you ever have been considered a leading man?” “Yes,” Dalí, played by Ben Kingsley, asserts, causing laughter to ripple through the live audience.

The clip announces the offbeat take that director Mary Harron has chosen for her biopic: she focuses on the surrealist master late in his career, past his prime, when he’s become a celebrity—a bit of a joke, and a kind of surreal artistic creation in himself. The film jumps forward to 1974, when we see the aging Dalí dyeing and waxing his moustache with the meticulous care he might put into a canvas. By now he only refers to himself in the third person.

Harron centres the film on Dalí’s oddball party years, when the septuagenarian would hole up with his wife Gala in New York’s St. Regis Hotel, hosting wild celebrations where, on any given night, you could apparently find circus contortionists, buffet tables with lobster sculptures, coke lines, or Alice Cooper. In many ways, that decadent art-world setting isn’t so far removed from that of Warhol’s Factory, where Harron set her critically lauded I Shot Andy Warhol. Like the father of pop art, Dalí had his share of hangers-on and social parasites.

So far so good. But Harron ultimately chooses to tell her story through the eyes of young artworld newbie James (Christopher Briney), an art-school dropout and Dalí fan who ends up working as the art star’s personal assistant/money runner. When he first witnesses one of Dalí and Gala’s famous parties, someone tells him, “Welcome to Dalíland.” It’s a pretty conventional way to approach a film about art’s reigning weirdo—and James comes off as bland next to Dalí and his sexually voracious wife (played by legendary Fassbinder muse Barbara Sukowa). Another problem is that we never see Dalí’s famous paintings and sculptures (a rights issue, presumably), only hearing allusions to the melting clocks and The Great Masturbator.

The film’s strength is the dynamic that Kingsley and Sukowa build between the codependent Dali and Gala—though they’re not given space to go deep enough here. Into her 80s, and decked out like a seventies-styled Gloria Swanson, Sukowa’s batshit Gala is as hungry for money as she is boy toys; Dalí, on the other hand, is a sexually stunted voyeur. Fame, it seems, has paralyzed his creative output as well—much to his decadent wife’s chagrin.

Kingsley is compelling as the artist, though not as whacked-out as you might expect. In his hands, Dalí is like an eccentric, confused child, as prone to flights of fancy as tantrums: watch him wail “Gala-a-a-a-a” when he wants something. And, amid a big performance, Kingsley manages to find the pathetic, vulnerable side of a great artist facing old age.

Still, a few token flashbacks, starring an underused Ezra Miller as the young artist who falls for Gala, do little to illuminate the real roots of his love-hate relationship with his wife. Sadly, Harron spends almost as much time focused on James’s boring hookups with vapid Dalí groupie Ginesta (Suki Waterhouse).

Overall, as promised in its title, the film is far more focused on the outrageous circus that surrounded Dalí than the man at the centre of the carnival. And even that carnival itself feels tamer than Harron intends. In one extended scene, the artist invites his young, female entourage to sit, bare-bottomed, in paint and then on canvases, creating a series of ass prints. Far from the height of scandalousness, they’re no Persistence of Memory—and like the rest of the film, may leave you feeling un-shocked, a little empty, and, well, bummed out.