Dance review: Neon wigs, red shin pads, and more colourful touches at Dancing on the Edge opening weekend

Wen Wei Dance has wild, Baroque-tweaked fun, while Juan Villegas explores his Sephardic Jewish ancestry and David Albert-Toth grapples with consumerism

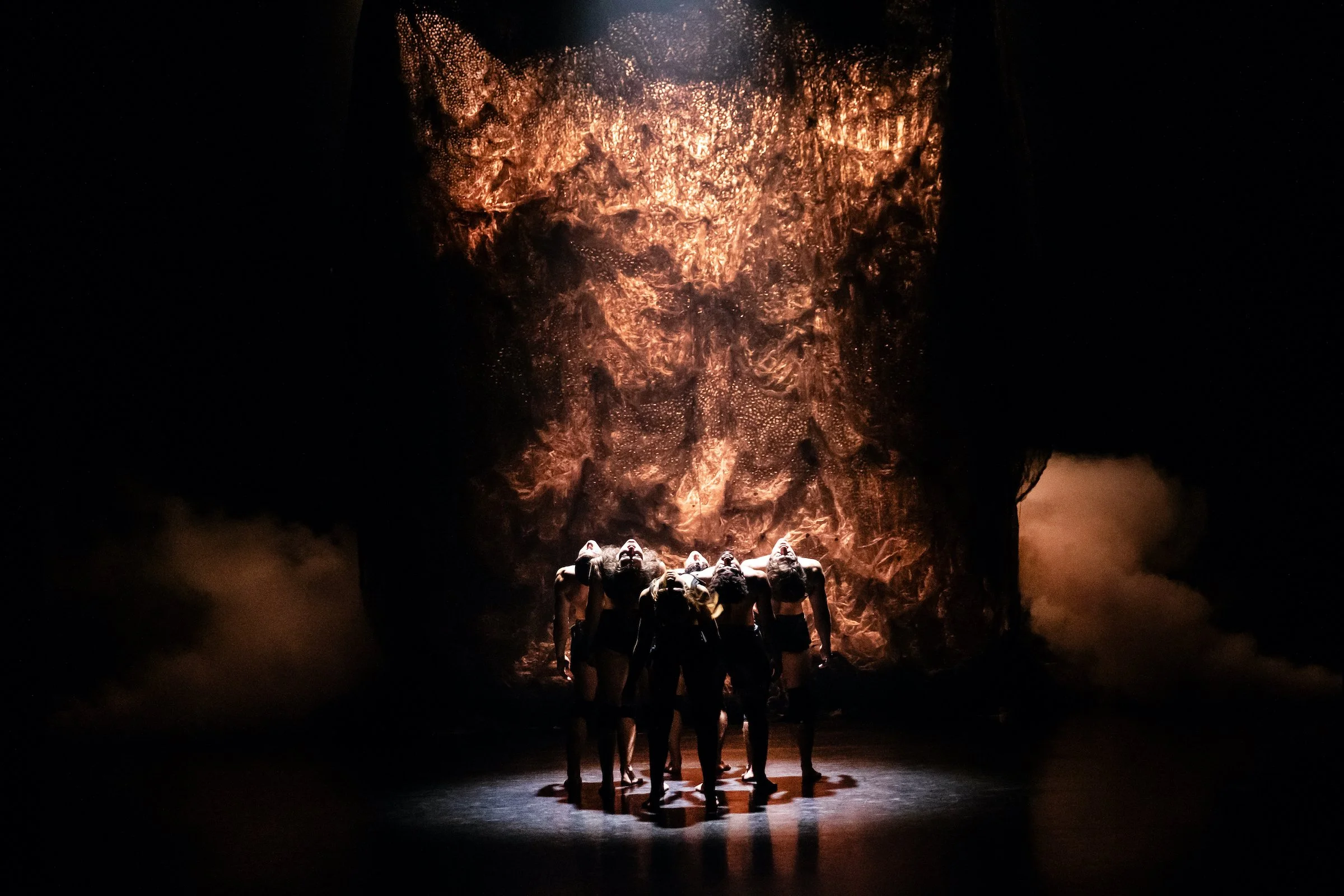

Barocco Rave’s RE I BUILD I US.

The Dancing on the Edge festival continues to July 15

ALL TOO OFTEN contemporary dance lives in the darkness, slices of light illuminating black-clad dancers on an otherwise shadowy stage. That’s why the playful bursts of colour—in terms of both costuming and vivid ideas—at Dancing on the Edge this weekend were so refreshing. And fortunately, that vibrancy came with conceptual depth.

As the fest opener, Wen Wei Wang and Francesca Lettieri’s two-part Barocco Rave set the tone, replete with neon knickers and wigs, and playfully inventive dance.

Both the Canadian and the Italian choreographer made the most of their honed, fearless, and individually expressive quartet of Vancouver dancers: Ariana Barr, Alexis Fletcher, Adrian De Leeuw, and Matthew Wyllie.

In Lettieri’s opening half, BEAT ARMONICO, the troupe moved to Baroque music, playing off its stylized rhythms, by turns mechanical, broken, and unhinged. The dynamics between the group members were ever-shifting; in the program notes, the Siena-based choreographer suggested she was trying to capture a kind of multitude of humanity—“not just a woman or just a man, I am at the same time many women and many men, many places, animals, cities, countries, families, memories, emotions, objects and people”. Moods shifted unpredictably from light to dark. At one point, the ever-expressive Fletcher’s maniacal laughter morphed into crying. Another elaborate game of chase suddenly turned dark, the equally arresting Barr grabbed and pulled by her outstretched legs by the other dancers. And then the entire, dreamlike world transformed again, from refined Baroque to club beats that suggested the rave in the evening’s title. It was a fascinating distillation of human experience.

Wen Wei Wang refracted a lot of the same ideas in wild new ways in RE I BUILD I US. The accomplished Vancouver choreographer seemed to be exploring the idea of rebuilding one’s identity, relationships, and emotions after catastrophe or shutdown—say, after a pandemic. But he did this in the most edgily playful ways, working collaboratively to highlight each dancer’s skills and quirks. That meant Matthew Wyllie might pull off breakdance floor work or sit behind a drum kit in his neon green wig, knee socks, and sunglasses. Or it meant Adrian De Leeuw crawled along the floor, his long legs collapsing under his weight. Elsewhere, Fletcher made a fun riff on body building, taking dumbbell curls to absurd extremes.

There was struggle in this eclectic piece, more laughter and crying, and a general relatable sense that we are all fighting to rebuild—and sometimes losing it in the process. (Here the Baroque strains, under sound designer Sammy Chien, fractured and devolved into electronic music even more.)

Life is messy, hard, unpredictable, and absurdly funny right now—and all of that, in its weird complexity, played out perfectly in these two pieces in ways that were hard to put into words but felt endlessly familiar.

A Bout De Bras. Photo by Robin Pineda Gould

Elsewhere at the fest, things were equally inventive in À bout de bras, in which soloist David Albert-Toth shared his “erotic desire” to gulp down a tantalizing can of Coca-Cola. He expressed a craving so fervent, witnesses were sure to keep thinking about the brand—and Albert-Toth—long after they’d left the theatre.

That dangling of the carrot, so to speak, was what the piece, co-choreographed and directed by Emily Gualtieri, embodied most strongly. The piece was a cleverly structured reflection on how capitalism consumes our daily lives, and it was impossible to look away.

The French title of the piece from Montréal-based company Parts+Labout_Danse translates to “At arm's length”, a theme that resurfaced as Albert-Toth struggled with the burden of constant consumerist choices.

Those decisions weighed heavy, and it showed in the dancer’s movements. Arm extensions were left purposely incomplete, Albert-Toth’s limbs rebounding back and forth before a crisp line could be made. He crumbled into himself, energy spent, over and over again. The theatre is intimate, so the audience could hear Albert-Toth’s limbs crack as he dropped to his knees, and could see the sweat drip from his nose as he paused in exhaustion.

What was most interesting, perhaps, was that Albert-Toth was not just dancing before the audience members but was talking to them. He began the piece with a humour-speckled speech about the importance of dismantling capitalism (a phrase repeated so many times that it became empty words).

He used myth rather than memory to drive his point home, recounting the tale of Tantalus, a Greek mythological figure stuck in limbo between rising water below and a low-hanging fruit tree above, both of which recede from his yearning hands when he reaches for them. That served as a metaphor for Albert-Toth’s own consumer desires, which were truly at arm’s length—ever unattainable, shunted out of reach by financial and systemic barriers.

At one point, Albert-Toth pulled and pushed himself around the stage on all fours, again and again, bursting into a frantic rap-like chant about his need to fill a void with material goods. The movement pattern started out almost sensual as a slow, carnal crawl, but quickly became a fast, desperate, and near-deranged full-body drag in his plea to attain gratification.

Edictum

Over on the EDGE One program, the concept of talking while dancing could be found in another piece. In Juan Villegas’s Edictum, the performer spoke Spanish. Some snippets were discernable, like the mention of Colombia, and the reenactment of a memory in which he was eating a dish with tomatoes. But much of his speech was lost on the audience, left up to interpretation.

The work, directed and choreographed by Vanessa Goodman, was a glimpse into Villegas’s Sephardic Jewish ancestry, and the generational impact of leaving one’s home to evade persecution. It was evident that Edictum comes from a deeply personal place, as we saw Villegas grapple with lost history. But there were moments amid the intimacy where Villegas broke out of his memory-like trance with incredible fortitude; sometimes he looked an audience member dead in the eye, and beckoned them to join him onstage with all seriousness. (No one did—we were left wondering what might have happened if someone had.)

Costuming by Carlos Chaverra played an important role in the piece: the eyes are drawn to Villegas’s matching sparkly red shorts and t-shirt with white stripe detailing, red shin pads, and brown traveller’s boots that squeaked against the floor as he readjusted his footing.

An old-timey radio playing crackling Spanish music also added depth, and Villegas engaged in a peaceful Latin dance solo, hips swaying and arms outstretched to an invisible partner. In reliving his family’s past, Villegas allowed the audience to experience and remember it as well.

Sophie Dow in a hidden autobiography. Photo by Tracey Lynne

EDGE One wrapped up with a hidden autobiography, danced by Sophie Dow and choreographed by Kiera Shaw. With fearless determination, Dow delivered on a piece that was both technically and physically demanding in its vast use of space and bold, unwavering movement. Spoken affirmations about the dancer’s hollow core and soft edges resonated on the soundtrack, guiding the journey along.

So far it's a strong and eye-catching range of dance at the Edge, and if there's any linking message it may be that self-discovery takes hard work. That might be through reconnecting with once-forgotten heritage, it could be finding connection after a long period of isolation, and it could be breaking free from capitalist constraints. Or it could be just donning a bright-green wig, knee socks, and sunglasses.