Emad Armoush bridges Arabic, jazz, and even flamenco worlds with new Rayhan project

Appearing at the Vancouver International Jazz Festival, the Syrian-born singer and multi-instrumentalist’s new quintet crosses cultures in captivating ways

The TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival presents Emad Armoush's Rayhan on June 29 at Performance Works at 2:30 pm; performance in person and livestreamed, for free. Find COVID safety protocols here.

ON A GOOD NIGHT—and I’ve never seen them have a bad night—Gordon Grdina’s Haram is the most exciting band in Vancouver. Combining an all-star cast of local improvisers with an array of Middle Eastern melodies, and driven by the absolutely massive rhythm section of bassist Tommy Babin and drummer Kenton Loewen, the group’s sinuous charm and exuberant energy is extraordinary. It’s also beautifully grounded by Grdina’s earthy oud virtuosity, and by the impassioned-yet-dignified singing of Syrian expatriate Emad Armoush.

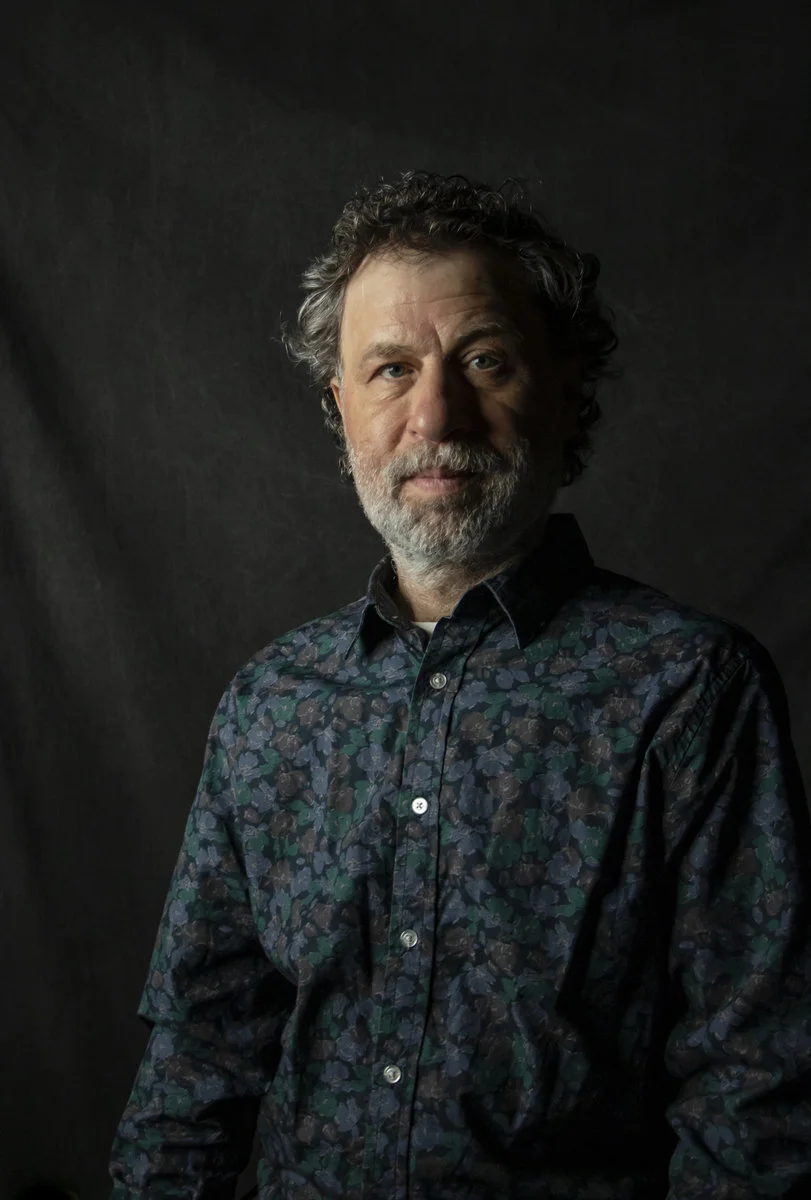

Emad Armoush

Unfortunately the very qualities that make Haram so sublime have also conspired to keep its presence in the city relatively muted. Assembling a big band of first-call soloists is never easy, and the logistics of this band are further complicated by Grdina’s propensity for multiple projects—I’ve lost track of how many other groups he has on the go—and, of course, by a pandemic that has made assemblages of Haram’s size not just logistically daunting but risky. (The group’s name, which means “forbidden” in Arabic, has certainly taken on another layer of meaning!)

So admirers of Haram should rejoice that singer and multi-instrumentalist Armoush has recently assembled a pocket-sized version, Rayhan, that with any luck will become a local staple. Based on the evidence of its debut recording, Fragrance, the new quintet has retained all of Haram’s brilliance but in smaller and subtler form; what it may have lost in terms of sheer, swaggering volume it’s gained in nuanced emotional range. The lengthy “Che Mali Wali”, for instance, opens with a meditative, improvised conversation between all five players, before they play through the tune in rough unison. That, in turn, is followed by Armoush’s throaty singing, and by a questioning solo from clarinetist François Houle that somehow combines Third Stream jazziness with the wailing quality of the Muslim call to prayer. It’s lovely stuff.

There are precedents for this kind of intercultural Arabism, of course, most notably Tunisian musician Anouar Braham’s many fine recordings for ECM and his Lebanese counterpart Rabih Abou-Khalil’s work on the Enja label. Rayhan, however, immediately establishes itself as unique on “A’tini l-Ney”, which is simultaneously deeply strange and hauntingly romantic. Building on the lunar soundscape of trumpeter JP Carter’s electronics, the tune then veers into Parisian café jazz courtesy of Armoush’s flamenco-accented guitar… And is that a hint of Stéphane Grappelli in Jesse Zubot’s digitally augmented fiddle?

The subsequent “Bint el Shalabiya” is a Haram-style stomp, and then on “When We Were Kids” Loewen comes to the fore, anchoring the tune with the kind of relentless backbeat that suggests John Bonham with jazz training. Rayhan might be Armoush’s project, and almost all of the tunes are rooted in Middle Eastern tradition, but it’s clear that all five musicians are allowed arranging and improvisational input.

“We’ve been playing together for a long time with Haram, as you know, and I’ve heard these guys have their own take on that repertoire throughout the years,” the leader says, in a telephone interview from his Vancouver home. “And it’s always like ‘Wow, that’s amazing! That’s so fresh!’ So everybody’s life experiences and musical experiences are at work with these songs, including mine. I didn’t want to do these songs in a traditional way, just mimicking the feeling. I wanted to keep the feeling intact, but I wanted to have my take on it, which I’ve been trying to do for years.”

That’s an important point. Don’t make the assumption that Rayhan is some kind of folk-musician-with-jazz-accompaniment project: Armoush is as experimentally inclined as any of his bandmates. And while many Syrian musicians have been driven abroad by civil war, he’s escaped the worst of that, having emigrated to the United States almost immediately after graduating from high school. There, he earned a degree in engineering, a trade that eventually brought him to Vancouver. And here, he recalls, getting laid off from his engineering job spurred him to take on music full-time.

“I was kind of lucky, I guess,” he says. “I was into flamenco, so there were performance opportunities. And I played percussion… I actually started percussion here, after moving to Vancouver. Then opportunities came with Arabic music. So I guess being versatile has helped me make a living with music, which I understand is completely hard—and it’s still hard, of course! It’s the versatility… I could do percussion here, sing there, play guitar somewhere else.”

Flamenco, Armoush adds, opened the door for the kind of boundary-crossing work he’s doing now with Rayhan.

“I had listened to it for many years before I even was involved in it,” he explains. “I loved the singing and how close it was to Arabic—although ornamented very differently, of course. To me, it was freer and more expressive, in a way. More raw than the Arabic approach, which is a lot more… How to say? Proper, I guess. You have to have a certain technique, but flamenco functions differently. As long as you can bring out a strong feeling, you can do it well.”

This translates, he adds, to the way his improv-oriented colleagues approach the traditional tunes they’re exploring. “The traditional aspects are so strong that you can go play ‘out’ for quite a while and still feel that home is waiting,” he says. “You can come back to it [the melody] without feeling jittery, or losing track.

“And the songs are just a reference. We’re trying to play music, and when music happens, referencing the song, that’s wonderful. To me, at least, it’s the listening aspect that matters, like ‘Oh, this sounds like good music being played here!’”

Good music? There’s nothing but great music on Fragrance, and no reason to expect anything else when Rayhan makes its live debut at the Vancouver International Jazz Festival this week. If that show is your first post-pandemic concert event, consider yourselves lucky.