Film review: You Will Die at Twenty takes a poetically allegorical journey into remote Sudan

Strong performances and dreamlike cinematography bring to life a story about fate

The Cinematheque streams You Will Die at Twenty to March 11

AMONG THE MANY aspects that draw you into You Will Die at Twenty—Sudan’s poetic and mesmerizingly shot first Oscars submission—first and foremost is the soulful, sombre performance by both its lead actors.

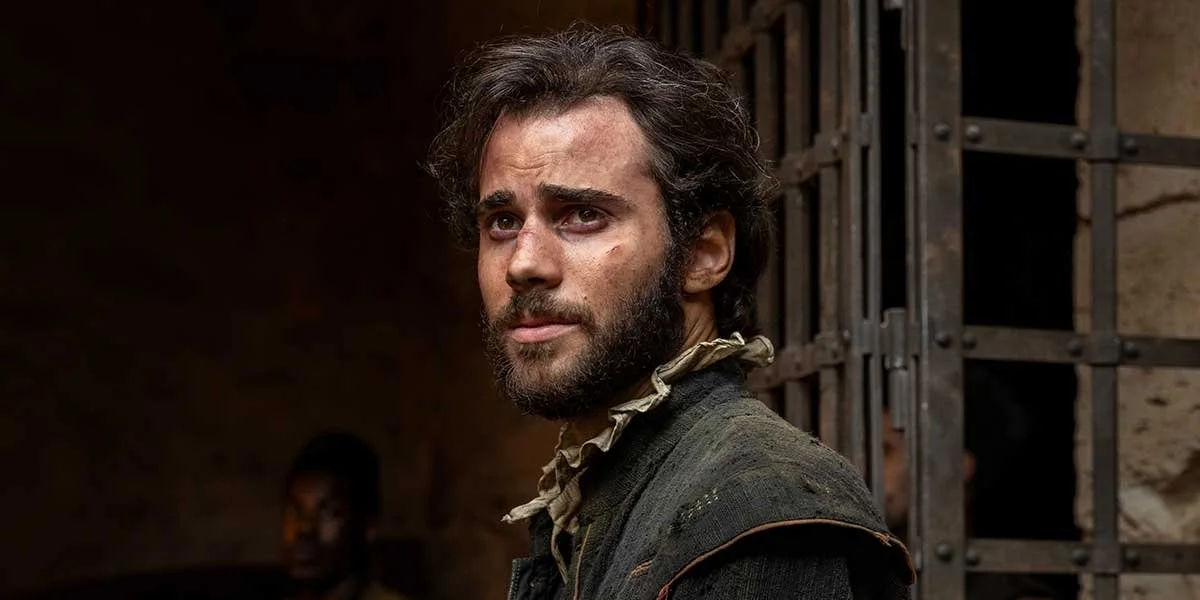

They play the same person, Muzamil, at different ages—Moatasem Rashid as a boy and Mustafa Shehata as a teen. The youth, who lives in a small village on the Nile, carries the burden of a prophecy in every look and action: he will die by the day of his 20th birthday. Rashid and Shehata show the weight of it quietly through their eyes, at first with resignation and sadness, and then simmering frustration and anger.

The sheik’s prediction comes in the movie’s headily shot opening sequence, in front of a conical clay mosque, where dervishes in dreadlocks and green robes join women wrapped in brightly printed toub veils, singing and celebrating Muzamil’s birth. When one of the dervishes collapses amid the frenzy, the baby’s fate is sealed.

The fable-like setup becomes a premise for writer-director Amjad Abu Alala, working from Hammour Ziada’s short story “Sleeping at the Foot of the Mountain”, to subtly explore the meaning of life, but also, metaphorically, to consider the larger implications of a society that resigns itself to fate and turns ever more to the closed world of fundamentalism.

Muzamil’s mother (Islam Mubarak) drapes herself in black death robes from day one, refusing to let Muzamil to leave her watch, play by the river, or even get an education. It’s not until he’s a teen that he’s allowed to learn to read—but only to memorize the Quran, under the instruction of the local sheikh, in an attempt to cleanse his soul in preparation for his death. He won’t even give in to the affections of a local girl who loves him.

But working as a shop-delivery boy, his convictions start to erode, when he starts taking bootleg alcohol to Sulaiman (Mahmoud Elsaraj), a man who has spent years abroad and lives with the local prostitute. The old man drinks heavily, and plays music on his radio, showing the teen old films of Khartoum and Cairo belly dancers—a world far outside the dusty streets of this town. In one of the film’s key lines, Sulaiman tells Muzamil, “You ask for forgiveness for your sins and yet you've never sinned. Try sinning.”

Cinematographer Sébastien Goepfert gives the film a heightened, dreamscape feel, right from the opening’s symbolic shot of a vulture standing over a dead cow. A recurring scene features a shard of light slicing into a mud hut where Sakira marks the days in black on the wall. There are also touches of magic-realism: in one dream sequence, Sakira holds her son in her arms à la Pietà.

Western viewers might find the pacing of the film slow, and the hero is by turns ambivalent, complacent, and conflicted. Alala, who spent years growing up in Sudan but now lives in United Arab Emirates, keeps the perspective nonjudgmental, and we have to untangle our own lessons. It’s important to remember that art that comes out of repression often has to speak through allegory. Ultimately, the film seems to speak most clearly to the human need for individual agency, beyond religious edict or superstition. And that’s where Shehata and Rashid’s performances become so important: they centre the metaphorical in authentic human emotion.

Together, they take us into a place Western viewers would normally never have the chance to go--onto the muddy shores of the Nile, or right into clay houses lit by oil lamps, up to the communal trays where people eat, or under the mosquito nets at night. It's an opportunity to see a new world with new stories--even when those stories don't offer easy answers.