Luke Parnell's Indigenous History in Colour brings more than a blast of neon to Bill Reid Gallery

The artist fuses past traditions with the politics and contemporary art of today

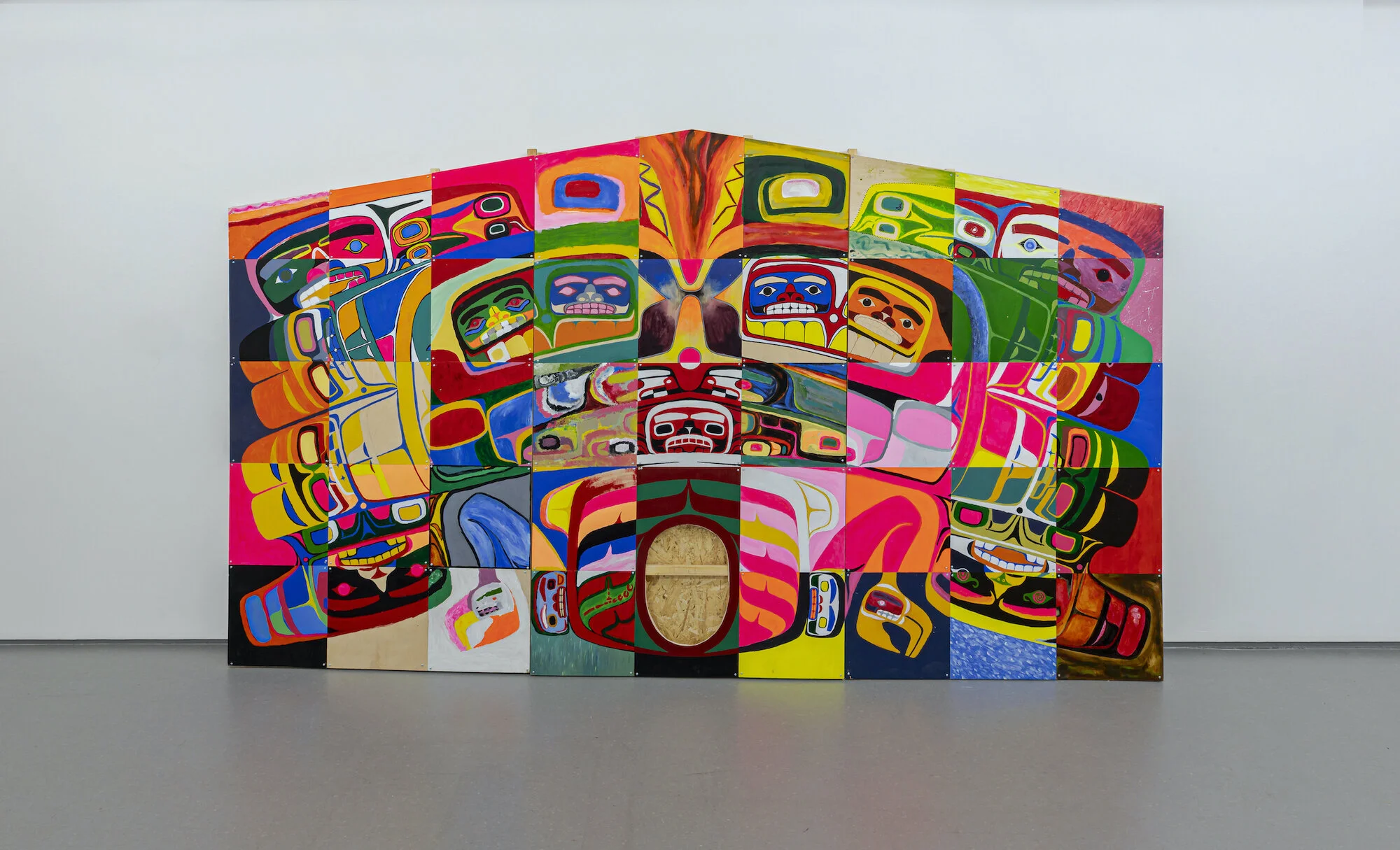

Luke Parnell’s Neon Reconciliation Explosion contains a stripped-down door that opens a world of disturbing meaning. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy MKG127 Gallery

The Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art presents Indigenous History in Colour from February 3 to May 9. A virtual opening celebration, featuring Parnell in conversation, takes place on Facebook Live on February 2 at 6pm

THE BRIGHT ACID colours hit you first when you see the work of Prince Rupert-born Nisga’a-Haida artist Luke Parnell.

In his new exhibition at the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art, he goes far outside the realm of traditional red-and-black formline. In the vivid digital print Bear Mother—depicting the prominent figure in Haida myth—he’s collaged electric hues of pink, yellow, purple, and blue.

But those blasts of neon are just the start of the multilayered ways that the Toronto-based artist is moving traditions forward. Contemporary art theory, pop culture, Instagram, comic books, and the pressing Indigenous politics of today: all of them find their way into the work of Parnell, who was also trained as a carver.

“The culture is dynamic and moving forward and it should not be stuck in the past,” he asserts in a phone interview with Stir. “And when I see other people experimenting in different ways, I see it, if anything, as upholding tradition.”

To understand the many experiences and studies that have led to the art that Parnell makes today, you have to go back to his years growing up in Prince Rupert. His Haida father and Nisga’a’ mother had Indigenous art on the walls, and family members, including his grandfather, shared the old stories with him.

“But it wasn't the same as it is now,” he reflects. “When we were young we were kind of ashamed to be Native. I didn't really embrace carving and stuff till I was in my late 20s. And I’d already studied conceptual art and relational aesthetics by then in school.”

Luke Parnell’s Bear Mother. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy MKG127 Gallery

Instead, as a teen, Parnell dreamed more of becoming a comic-book artist. Later, he went to the Ontario College of Art and Design to pursue a diploma in sculpture. After that, he returned to the West Coast to apprentice with master Tsmishian carver Henry Green for three years. Parnell marvels that, until then, he hadn’t carved before, and he knew little about the formline of his heritage.

But gradually it became clear that carving traditional Northwest Coast art wasn’t for Parnell. “I didn’t want to make things for the market,” he says simply. “I didn’t want to be a commercial artist anymore.”

He longed to merge the contemporary concepts he’d learned at school with the traditions he’d gleaned from carving. And so, in the mid-2000s, he returned to the now OCAD University to pursue a bachelor’s in fine arts.

Laughingly, he recalls that, in one of his first meetings with his fellow students, he introduced himself as an “academic with a chainsaw”.

Parnell went on to get his master’s in appied arts from Vancouver’s Emily Carr University of Art + Design, and he’s an assistant prof at OCAD U today.

Luke Parnell’s Arts of the Raven. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy MKG127 Gallery

He traces his conceptual shift in art-making back to 2007’s A Brief History of Northwest Coast Art (now part of the National Gallery of Canada’s collection). Employing carving and traditional red and black designs over 11 panels of cedar and plywood, it is a stunning depiction of the way the old masters’ work was interrupted by colonization. The panels’imagery is literally disrupted by three white-washed boards in the middle, before the gradual revival of the old ways by a new generation.

Here at the Bill Reid Gallery, you’ll see more recent pieces, in a variety of media.

Among the most visually arresting and politically charged is 2020’s Neon Reconciliation Explosion, in which the artist built and carved a traditional Northwest Coast housefront and then invited 55 community members to paint their own impressions of reconciliation in bright neon paint. At the bottom centre of the elaborate structure sits Parnell’s own contrasting contribution: a bare plywood doorway with the rough carved initials “CB” and “TF”.

They memorialize Coulton Boushie and Tina Fontaine. Boushie was the 22-year-old Cree man shot on a Saskatchewan farm; the farmer who fired the gun was acquitted. The 15-year-old Sagkeeng Fontaine went missing, her body later retrieved from Winnipeg’s Red River. In both cases, the people accused of their murders were acquitted.

“I just sort of over the years had lost faith in reconciliation, and the trials of Coulton Boushie and Tina Fontaine had made me lose faith,” Parnell explains, adding the coloured parts of the structure stood there long before he decided how to design the door. “It took me a year because I didn't know what I was going to do, and also another part I struggled with is I didn't want to use them for my piece. So I decided to just to carve their initials.”

Equally thought-provoking is the sole short-film work in the exhibit, 2018’s Remediation. The piece was a critical response to a 1959 documentary of Bill Reid joining an expedition to “salvage” historic totem poles from Haida Gwaii, cutting them down and transporting them to UBC. In Remediation, Parnell splits his own totem pole in half, carrying it across the country to the coast where he then burns it on a deserted Haida Gwaii beach.

“I watched it as a kid, and later as an adult it struck me how condescending it was,” Parnell explains of the 1959 documentary, “how it told people they were cutting them down because the Haida didn’t exist anymore—like we lacked authenticity or something. And that irked me.

“All these anthropologists and Bill Reid always went out of their way to point out that the Haida aren't the same today as the ones that made those totem poles,” he adds.

And the sacrificing of his own intricately carved pole? “I burned it to show objects aren’t really important; it’s the people that are still here.”

Luke Parnell totes his own, cut-off totem pole across the country in the short film Remediation.

A quote by Reid in that same film stuck with Parnell as a kid—and in many ways still drives him today. Reid commented that he didn’t feel the Northwest Coast style could be taken much further than where it was. It’s something Parnell disagreed with then, even as he looked up to Reid as an icon. And along with an exciting new generation of boundary-pushing Northwest Coast artists, he has proven the statement wrong.

Still, Parnell doesn’t see himself as an activist, per se. “I think it becomes political,” he says of his work. “Indigenous art is always political. I can’t shy away from it.”

The storytelling of his ancestors drives his work just as much. Bear Mother, he says, started as an Instagram post he created for National Indigenous Peoples Day, experimenting with colour theory.

“For a long time I wouldn’t use a lot of traditional stories in my work,” he reflects. “I felt like Northwest Coast stories were so widely appropriated that we don’t need to share them. But the stories are so amazing. They're part of our history and I was longing for that connection.

“But it took, like, 10 years,” he says. “That was good because I started writing my own stories.”

And viewing the compelling work in the exhibit here, you get the feeling there are many more of Parnell’s stories to be written--in every imaginable colour.