New book curated by Yosef Wosk features photographs by celebrated Israeli photographer Nachum Tim Gidal

“You do see some smiling children, but you also see sometimes a patient look, sometimes a painful look.”

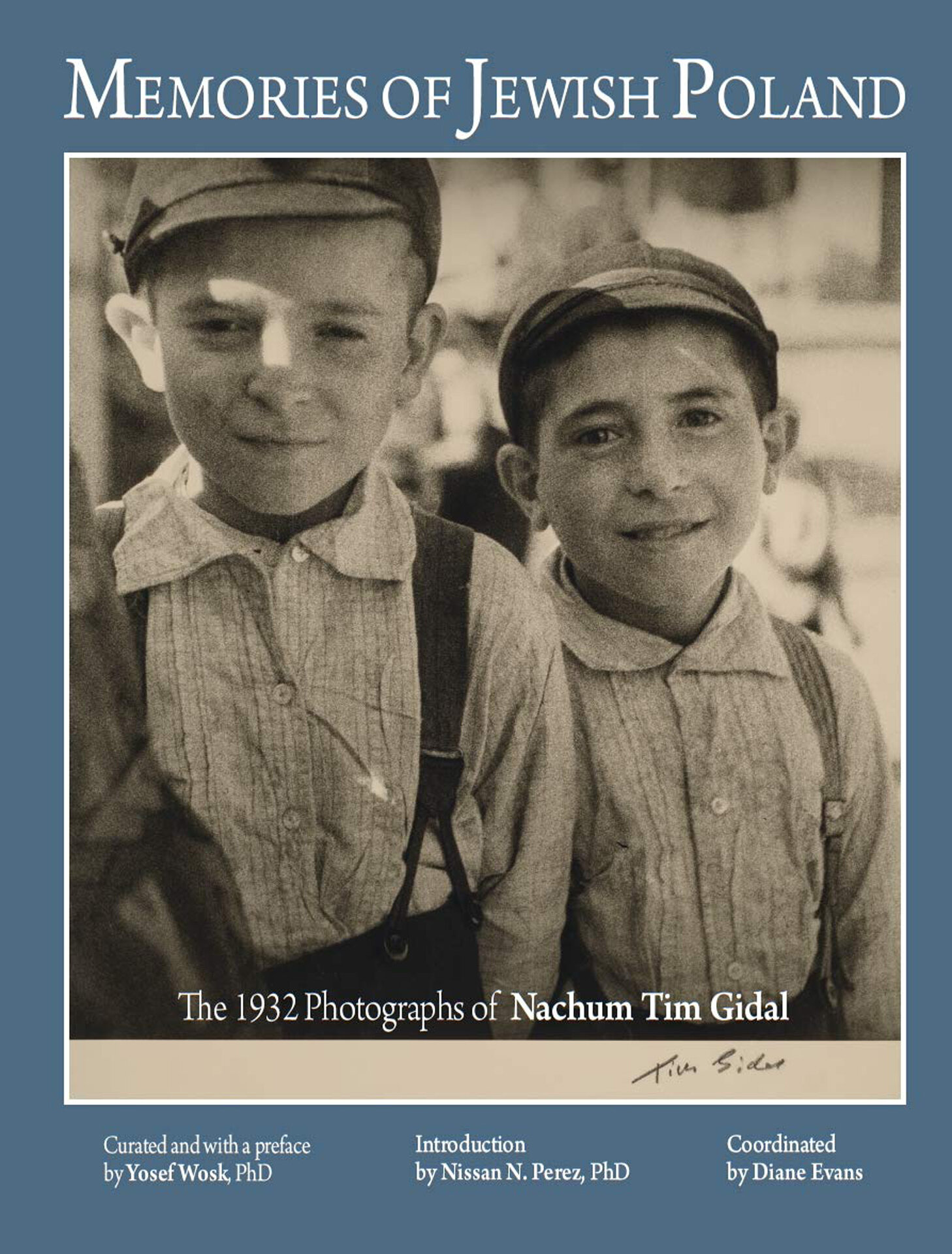

Brothers, Tim’s cousins. Lowicz, Poland. 1932 by Nachum Tim Gidal is among the images in Memories of Jewish Poland: The 1932 Photographs of Nachum Tim Gidal.

Yosef Wosk launches Memories of Jewish Poland: The 1932 Photographs of Nachum Tim Gidal on February 11 in a Prologue event of Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival (February 20 to 25).

VANCOUVER PATRON OF the arts Yosef Wosk, an Officer of the Order of Canada, was flipping through a copy of Hadassah Magazine in 1991 when he came across a photo that struck him. Called Night of the Cabbalist, it was taken on Lag b’Omer, a Jewish religious holiday, in 1935 in Meron, upper Galilee, in present-day northern Israel. The black-and-white image depicts a man lying against the mausoleum of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai under a full moon. Wosk was preparing for a sabbatical in Jerusalem when he stumbled upon the snapshot, which led to a lasting friendship and a death-bed promise.

“When I saw that photograph with the moon in the background, I felt I was looking at a picture of myself taken before I was born,” Wosk tells Stir. “It’s in one of my favourite places in Israel, in the North in Galilee, in a very spiritually evocative town. I felt that the photograph had touched me directly. That’s why I tore it out from the magazine and took it with me [to Jerusalem]. I really wanted to find the photographer.”

The photographer was Nachum Tim Gidal. Born Ignaz Nachum Gidalewitsch in Munich in 1909, he had an influential decades-long career as a photojournalist, with works appearing in newspapers and magazines throughout Europe. Gidal was 23 when he went on his first trip abroad, to Poland, to visit relatives and to see “exotic” Eastern Jews. From 1942 to 1945, he was the chief staff reporter for Parade, the British 8th Army magazine, capturing events in Europe, North Africa, India, and Singapore, among other places.

Wosk eventually made contact with the legendary photographer near the end of his sabbatical, quite by chance. He had nearly given up when he saw an ad on a lamppost for a store called Silver Print Gallery and Archive, which carried old Israeli photography. He asked its owner, a photo historian, about Gidal. She knew him personally and offered to make an introduction.

Wosk and Gidal became fast friends and stayed in close touch; over ensuing years, Wosk would end up purchasing the finest and largest collection of Gidal’s photography in the world outside of Israel.

Shortly before his death in 1996, the eccentric artist requested that Wosk publish a specific set of images—the ones from his Polish sojourn.

Memories of Jewish Poland: The 1932 Photographs of Nachum Tim Gidal is the result. Wosk will launch the book in a Prologue event of the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival. Running February 20 to 25, the fest features writers from Canada, the United States, Israel, Great Britain, and Chile in a mix of limited-capacity in-person events and virtual happenings. Wosk will join Alan Twigg in conversation from the JCC’s Zack Gallery for the virtual release on February 11.

Uncle Yukel, head of the community. Lowicz, Poland, 1932 by Nachum Tim Gidal.

Wosk is a writer, poet, art collector, scholar, educator, and philanthropist who supports museums, libraries, social services, health care, education and nature and heritage conservation. He curated and wrote the preface for the hardcover book, published in collaboration by Gefen Publishing House in Jerusalem and Vancouver’s Aryel Publishing House. Coordinated by Diane Evans and with an introduction by photography historian Nissan N. Perez, Memories of Jewish Poland is a portrait of the Gidal through photos from Wosk’s own collection and from the Israel Museum Collection.

The book includes Gidal’s notes for a 1984 exhibition in Tel Aviv. He explains how, during his European travels, he felt as if he had passed through an invisible curtain that once separated East and West and that had opened. “I was made to feel the unifying presence of Jewry,” Gidal wrote.

Yosef Wosk. Photo by Joshua Berson

In bringing the book to life, Wosk heeded Gidal’s instructions to use little in the way of text. Each page features a single image and nothing else; there are no descriptions of any kind. (Basic information appears in the list of plates at the very back: “Tailor shop, Cracow”, for example, or “Elderly man on a street corner, Warsaw”.)

“You do see some smiling children, but you also see sometimes a patient look, sometimes a painful look,” Wosk says. “Sometimes you see the burden of their labours, trying to make a few pennies to survive, then you see some of the students in the street, in their 20s and 30s.

“His natural rhythm was to let the photograph speak for itself,” he says. “Very few…are posed. He was able to achieve that direct intimacy, that trust, as if to say ‘I have no agenda. You’re expressing what you are in the moment.’ That’s why so many of the photographs are so sincere.”

It’s up to viewers, then, to interpret the images and feel what they want or need to feel upon looking at them. Perhaps it’s more appropriate to say Gidal “embraced” the moment rather than “captured” it, Wosk notes.

What you can’t help but consider while looking at the collection is that it is unlikely that many of the subjects, some of whom were Gidal’s relatives, survived the war. As Wosk notes in his preface, of the 3.3 million Jewish residents of Poland before World War II, only 380,000 were still alive by 1945.

Through his work, however, Gidal gave new life to many. Symbiotically, Memories of Jewish Poland—and the Jewish Book Festival itself—are keeping the cycle going.

“I learned from him and his life before me,” Wosk says. “Now he’s living on as we’re continuing his story a generation after he has passed on.”

Watchman of the old Jewish cemetery, Vilna. 1932, by Nachum Tim Gidal.

Fiddler and his son, performing on the streets of Warsaw, 1932, by Nachum Tim Gidal.

Yosef Wosk in conversation with Alan Twigg for the launch of Memories of Jewish Poland: The 1932 Photographs of Nachum Tim Gidal is a free event; registration is required. For more information visit Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival.