Dance review: PIÑA celebrates Philippine culture through seamless blend of textile, sound, light, and design

FakeKnot artistic director Ralph Escamillan’s new work shines a light on its namesake traditional fabric

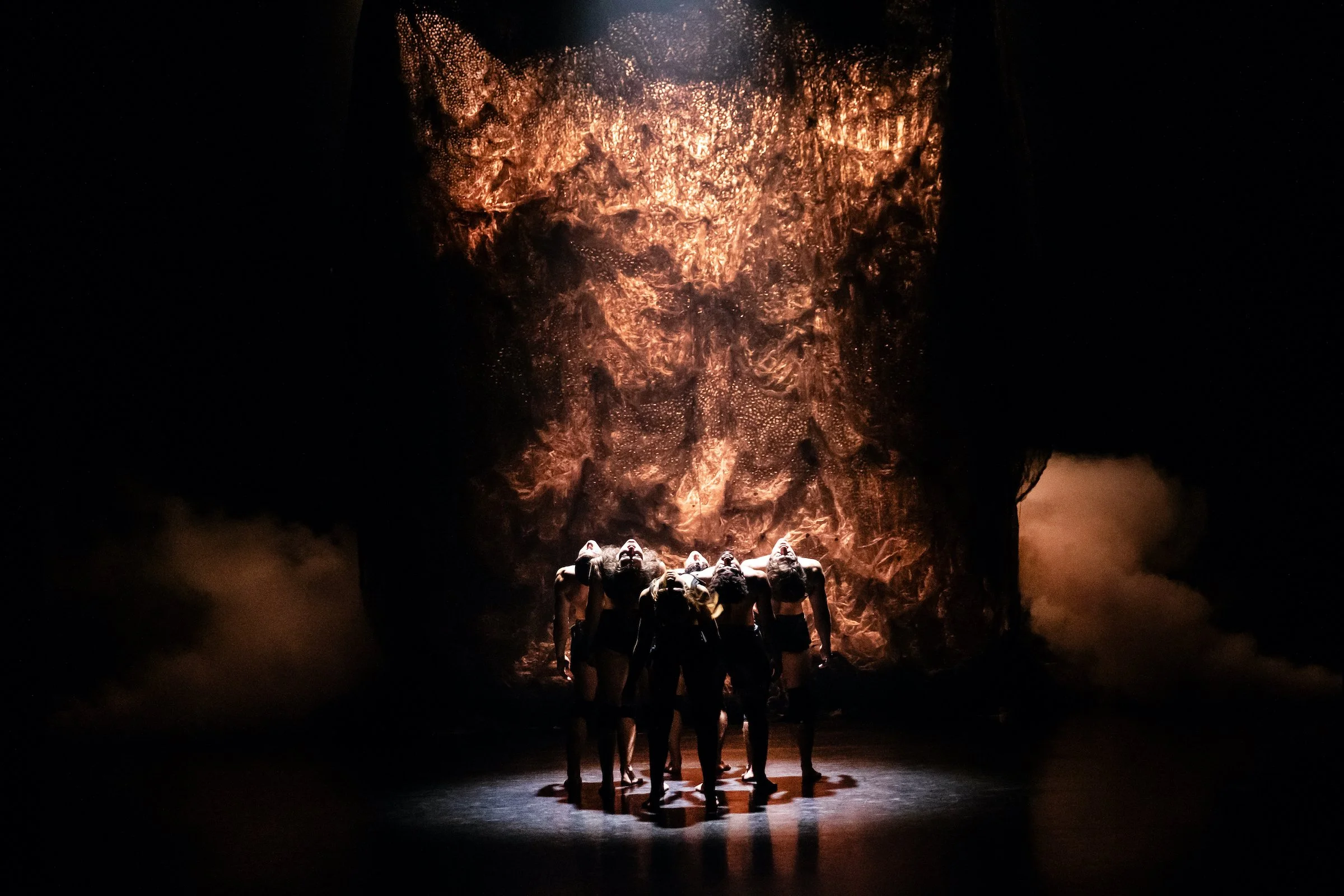

PIÑA. Photo by Rydel Cerezo.

PIÑA. Photo by Rydel Cerezo

SFU Woodward’s Cultural Programs and The Dance Centre present PIÑA to May 6 at 8 pm at SFU Goldcorp Centre for the Arts

PIÑA OPENS WITH the theatre lights on and four performers casually hanging out on stage, each one wearing what looks like an extra-tall set of butterfly wings that soar straight upward atop their shoulders and drape down to their feet. Diaphanous and the colour of faint gold, the structures are constructed out of the work’s namesake fabric.

The national textile of the Philippines is made from the leaves of pineapple plants. In the work by FakeKnot artistic director Ralph Escamillan now having its world premiere in Vancouver, piña is more than a prop and a set piece but a performer unto itself, even the star of the show, a huge sheet getting its own round of applause on opening night.

In paying homage to this historical material, Escamillan celebrates his culture and the endurance of the diaspora through a seamless blend of dance, design, light, sound, and textile. The work’s opening feels more like a community gathering than a staged show, the artists greeting and smiling at audience members before stepping into a lovely, gentle folk dance. The steps are simple and geometric, the performers moving in and out of a square shape; they don big smiles, turn shoulder to shoulder, and bow to one another, all to uplifting music. Escamillan, Tin Gamboa, Justin Calvadores, and Danah Rosales, who form the all-Philippine ensemble, appear as proud as peacocks as they parade the sheer cloth. There’s a genuine sense of joy from the get-go.

Set to an original score by Kimmortal!, PIÑA shifts to a standout segment that begins with Escamillan lying on the fabric on the floor like a goddess, lip-syncing to a smoky female voice singing lines like “piña how you cover me...make me feel divine” atop old-timey piano. He sashays and partners with the piece of cloth, folding it up into the shape of a swaddled baby, cuddling it adoringly in an instant that’s just so sweet.

As the piece progresses, the mood shifts, the lighting becoming an increasingly distinct element. In one scene, a crew member pushes a single spotlight across the stage to barely illuminate the dancers in Twister-like poses, continually placing one hand and one foot on the floor in different configurations. At times, they slam their bodies down harder and lift themselves up again and again, a nod to diasporic resilience. A sliver of light against the floor becomes a tightrope; the dancers later slide between another’s legs as if threading a needle. When the dancers, dressed head to toe in white, each stand in front of a horizontal blue light on stage in front of them, they’re aglow for an entrancing sequence that focuses on graceful hand gestures. As the tempo escalates and the beat becomes more clubby, light pulses onto these ghostly figures, playing tricks on the viewers’ eyes. The versatile fabric becomes a billowing wave that projected lines of light slide down like rain on a window.

Escamillan’s impeccable sense of rhythm is evident throughout, and there’s perfection in the dancers’ pacing. A steady sound of tock tock tock eventually builds in tempo, perhaps echoing a step in the process of piña-making? Elsewhere, Kimmortal’s score swells from staticky ambient noise to lush orchestral harmony.