New voices bring fresh life to BC's jazz scene as TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival prepares to open

Trumpeter-bassist Feven Kidane, guitarist Alvaro Rojas, and multi-instrumentalist Andromeda Monk are part of a new generation putting their own spin on the form

Feven Kidane. Photo by Diane Smithers

Alvaro Rojas. Photo by Tyler Wilson

Andromeda Monk

Coastal Jazz presents the TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival from June 24 to July 3

THE CONSENSUS IS in: this is an exciting time for jazz and improvised music in British Columbia, and that’s not only because the 2022 edition of the Vancouver International Jazz Festival is just around the corner.

True, the annual festival is nearly back to its pre-pandemic size, and recent changes to its formerly fractious board augur well for its future. But the real reason for the scene’s growing buoyancy is the arrival of a new crop of artists.

These younger musicians are bringing with them new sounds and new approaches, of course, but also a renewed sense of the music as a collective endeavour. That’s not new in itself: the same could be said about the Vancouver performers who coalesced around the Cellar nightclub in the late 1950s, or the renegades who formed the still-vital New Orchestra Workshop (NOW) Society two decades later. But in an age of mass distraction, it’s a necessary revival.

Are we heading for a creative-music renaissance in Vancouver, as 24-year-old multi-instrumentalist Feven Kidane claims? That remains to be seen, but the current confluence of musicians, venues, and scene cheerleaders suggests that we are.

Plant biologists like to talk about hybrid vigour: the boost in size, health, and productivity that emerges when different but copacetic lines of DNA merge. We may be seeing something similar in music: younger improvisers beginning their careers in Vancouver are all informed by jazz, but are resistant to genre boundaries. And given Vancouver’s increasingly diverse population, they’re also bringing an international perspective to their work; many are immigrants or the children of immigrants, and naturally want to blend their own heritage with North American music, often using 21st-century technology alongside more traditional sounds.

Kidane is a prime example. Born in Canada to Ethiopian and Eritrean parents, she’s adept on trumpet, electric bass, and studio electronics, and fluent in various jazz styles, progressive rock, and electronic dance music. Her overall project, she says, is to “decolonize jazz”, and while that might confuse those who see the music as inherently anti-colonial, having been defined by working-class Americans of African descent, she has a fascinating spin on what that means.

“Decolonial, for me, means forgetting what you ever heard about the music,” she explains. “You don’t even have to know the person or how they play in order to make something beautiful. And broadening the horizons of who you play with is very important, because you’re not only playing with a person’s instrument, you’re also playing with their spirit and ancestry and where they come from musically.”

In her various bands, Kidane has worked with young performers of Asian, Indigenous, and Hawaiian ancestry, but she’s also actively pursuing relationships with older musicians, most notably bassist Clyde Reed, a relentlessly creative veteran of the Vancouver jazz underground. (She’ll bring a quartet with Reed, drummer Jamie Lee, and keyboardist Suin Park to the Ironworks on June 28.)

Her generation, she stresses, “is becoming pretty open to the thought of mentorship. People are seeking out that kind of relationship across generations because legends are all we have in the music. Legends and legacies are what keep us going and learning as young cats, and especially in the improv scene there are people that have many a story to tell.”

And the exchange isn’t only a one-way street, she adds. “There’s a reason why Miles Davis, when he got older, was playing with younger cats, and I think that the people in my generation that are really digging into the history of music can see that relationship, and they seek it out. Like, I’ve been able to play with Clyde a few times now, and he’s a lot older than me, but I don’t think the spirit of the music knows any age. It needs many generations crossing paths in order to keep it fulfilled and propel it forward.”

As for what she’s bringing to the exchange, Kidane says that she’s increasingly drawn to working with her Ethiopian and Eritrean heritage. “A lot of our traditional music revolves around insane vocal melisma, and so I try to channel that type of voice into what I would write for a jazz group,” she notes. “I’ve also done some electronic stuff that incorporates samples of singers playing with masenqo, which is a one-stringed bowed instrument.”

But free improvisation, which Kidane describes as a way of “communicating kinesthetically through breathing, through sound, through the philosophy of your music”, is also essential to her practice.

“It makes us better people, essentially, because you’re working with a team that you may or may not know all that well, and you’re figuring out how to work as one unit,” she says. “I think it’s crucial to human development, actually.”

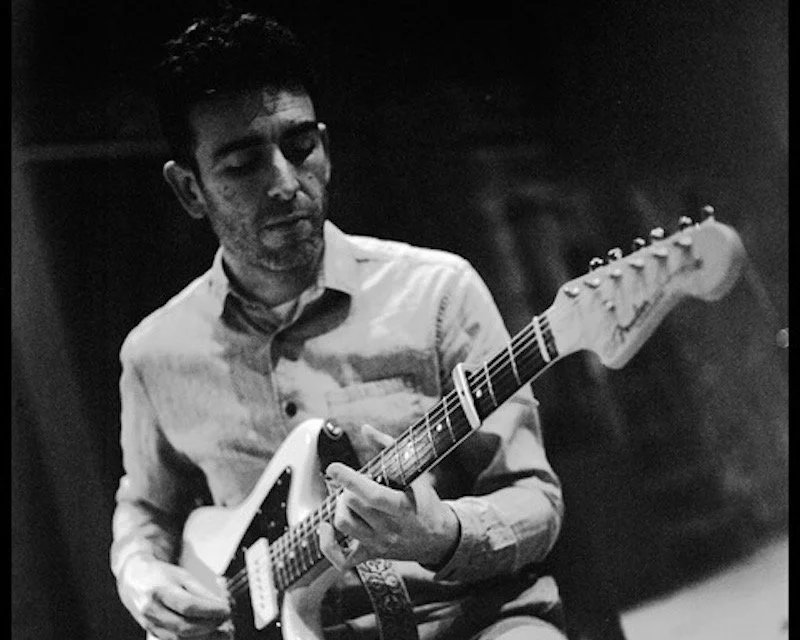

Alvaro Rojas

Capturing a new cultural hybridity

ROOTS AND futuristic explorations are also important to 39-year-old guitarist and composer Alvaro Rojas, whose Gran Kasa band plays David Lam Park on July 3. Family commitments have kept him from appearing locally as much as he might like, but he’s quietly developed an unusually sophisticated and personal sound.

Born in Peru but raised from an early age in Canada, he sees his music as a synthesis of his varied experiences, from playing Eddie Van Halen–inspired electric guitar to spending his pandemic downtime crafting the decidedly dreamy solo soundscapes that can be heard on his online-only album Moondog.

Vancouver, he says, is the perfect place to pursue cultural hybridity. “I don’t think anybody is just into one kind of music or culture or movies or food,” he explains in a telephone interview from his home. “Especially here. Like ‘What do you want to eat for dinner tonight? Shall we have some amazing Chinese food, or sushi, or Mexican food?’ It kind of goes like that with all types of culture. You can just mix and match things, take what you want and enjoy it all.

“I’m definitely more Canadian than I am Peruvian,” he continues. “That’s been made very explicit to me every time I go down there, or every time I try to talk to a native Spanish-speaker. But it’s this background element to my life, and to my music. I do speak Spanish, and I love cooking a bunch of recipes from Peru, and checking out different music and artwork and stuff from there. This cultural element is a part of my background, and I feel that it’s just something that I can dip into and connect with in a different way—and that’s what the Gran Kasa album and band are all about. Like, ‘Let’s explore this a little bit.’ We’re not trying to recreate it or be some sort of authentic Peruvian band or anything like that. It’s more just about having this other palette of colours to draw from. It’s part of me, and it’s part of my sound-world, so I don’t know… It’s awesome!”

One can, however, expect Gran Kasa’s David Lam Park show to feature the sunnier side of Rojas’s sound, along with new music he’s writing for a followup to the band’s 2020 debut. “I’ve been checking out all this cumbia music lately, so that might sneak its way in there,” the guitarist says. “I can’t help thinking that the park is not really the venue for a bunch of brooding, slow music. You want to have some uptempo kind of stuff, so maybe that’s where we’re going.”

James Meger’s How to Do Nothing (with Andromeda Monk).

Electronic music and minimalism

JUST WHERE multi-instrumentalist Andromeda Monk is going is somewhat harder to say.

Having studied composition at the university level, played saxophone and bass clarinet in various jazz configurations, and explored the inherently abstract options of the no-input mixing board—more on that later—she has options. But as de facto leader of the sextet Littles, she’s mostly just marvelling at her luck at finding such sympathetic collaborators.

The band, which also includes Kidane on bass, violist Lucy Strauss, guitarist Matthew Arianatnam, clarinetist Natasha Zmo, and drummer Adrian Avendaño, originally came together to do a one-off show sponsored by the Carnegie Community Centre’s music program. Like so many other concerts during the plague years, that was cancelled—but the band has continued, and will play the Ironworks on June 27.

“In preparation for that gig, we got together and improvised one night, the six of us, and the chemistry was obviously there right from the beginning,” Monk recalls. “As soon as we had played for a little bit, I was like ‘Can I write for this group?’ And everyone was like ‘Yeah! We’re completely down.’ So I was very, very lucky that this group just happened to come together that way.”

With Littles, Monk is getting to explore some of her current obsessions, including structures inspired by electronic music and minimalism—or, as she puts it, “extreme repetition”.

“I haven’t really got the band to come around to doing it as extreme as I would like,”she says good naturally. “I would like to play a thing for 10 minutes, you know. Play one two-bar passage for 10 minutes. So far we can do two-and-a-half minutes, so we’ll see.”

But she also notes that since Littles’ upcoming show is a jazz-fest production, the band will have to find “a happy medium” between trance-inducing modules and no-holds-barred improvisation. This is fine by her.

“The big problem with improvised music is that if everyone isn’t listening 110 percent, it just becomes kind of a mess,”she says. “But when I’m improvising with this group, it actually feels as though we all know how the piece goes—which is something I’ve never experienced in another improvised setting. The chemistry with this group is really unparalled, in my experience. Everyone is very, very giving with their ideas, and everyone is always bringing something very beautiful into the mix. But it’s never at the expense of everything surrounding it, so that’s quite wild.”

It also suits her primary instrument, which needs some explanation. No-input mixing board is a sonic innovation that’s been around for just 20 years; it’s basically a way of using a mixing console as an electronic tone generator. By feeding the board’s output back into its input a variety of striking pulses, buzzing, and whistles can be accessed—but a these are also strikingly unruly, making music from them demands intuitive flexibility and split-second reflexes.

“It drastically, drastically changed the way that I think about music,” says Monk, who’ll also explore this unusual instrument with bassist James Meger’s band How to Do Nothing, at the Roundhouse Community Arts and Recreation Centre on July 2. “Previously I was more of a composer and a songwriter, and it was all about making a clever structure. I would take months to write things.…It was very laborious: thinking about every word, thinking about every note, thinking about every way that it could be interpreted—and overthinking it, at the end of the day.

“With no-input mixing board, even if you have everything plugged in the same way and all the knobs set the same way, and you take a picture of it to make sure that it’s going to be the same, you won’t get the exact some thing ever again, because it’s extremely finicky. And the more broken it is, or the more dust there is in the mixing board, the less likely it will be to do the same thing—but the more exciting it will be.”

Making allowances for such an unpredictable collaborator also ties in with Monk’s musical philosophy of improvising—and with her belief that the way we make music also reflects our vision of a more open and caring society.

“Music where everyone is making it together in the moment is a model of how we need to work together,” she says, reflecting a view that’s part of many an improviser’s credo. “Art can be a space where we can tune in to something else—something that is more magical, like this special other world. But what the other world is for, and what’s in it, says something about this world and what we want to do with it.”