Film reviews: Rendez-Vous French Film Festival's Babysitter and That Kind of Summer explore gender and sexuality in wildly different ways

From Quebec, a manic satire of sexism, and a defiantly nonjudgmental look at female sex addicts

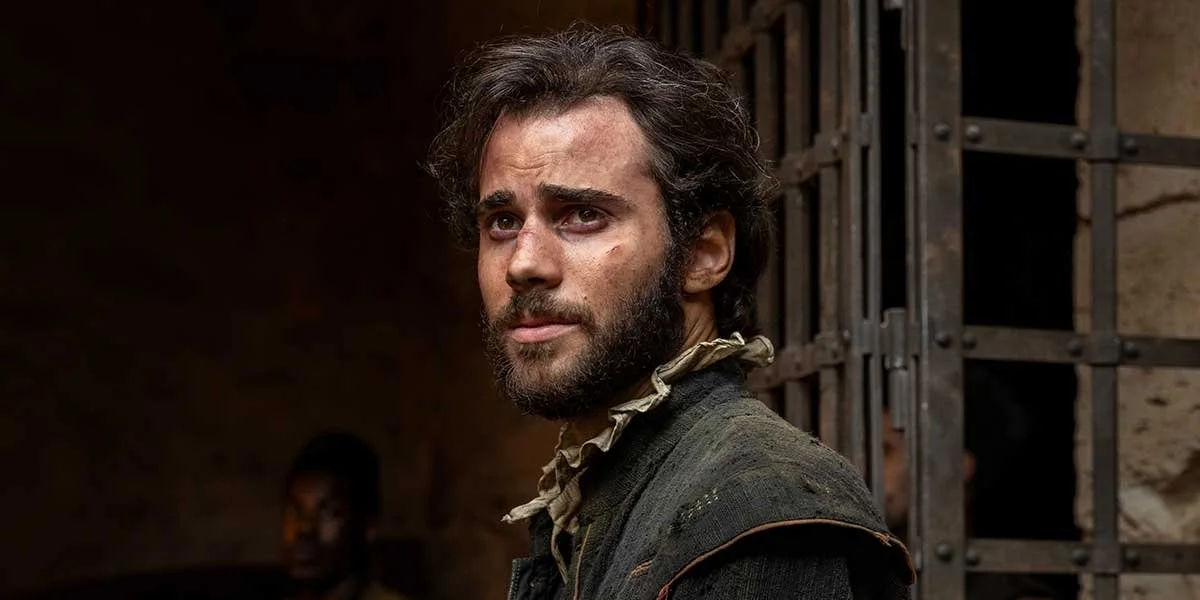

Nadia Tereszkiewicz is a standout as the titular character in Babysitter.

Rendez-Vous French Film Festival presents That Kind of Summer (Un été comme ça) on February 23 at 3:30 pm and Babysitter on February 25 at 3:30 pm, at SFU Woodward’s

TWO QUEBEC FILMS at this year’s Rendez-Vous French Film Festival take bold and fearless looks at sexuality.

Actor-director Monia Chokri’s Babysitter plays out like a maniacal, hyperstylized, triple-caffeinated comedy of manners.

In her sophomore film, which debuted in Sundance Film Festival’s Midnight section, Chokri adapts a Catherine Léger play into an absurd, Skittles-hued sexism satire.

The film opens on a frenetically edited, testosterone-fuelled night of carousing, middle-aged Cédric (Patrick Hivon) and his buddies boozing and ogling while attending a blood-spattered mixed-martial-arts match. It ends with the wasted Cédric planting a kiss on a live-TV reporter, an incident that goes viral. He loses his job as a result, and embarks on a novel-length apology letter with his journalist brother Jean-Michel (the rubber-faced Steve Laplante).

Cédric’s wife, Nadine (Chokri herself), meanwhile, could care less: zombified with a new baby at home, she’s simply too exhausted by 3 a.m. feedings to listen when the men try to mansplain their awakening to the misogyny in the world. She flees back to work—or at least, that’s what she tells Cédric, instead hiding out in a tacky motel with a heart-shaped jet tub.

Enter the titular character Amy (Nadia Tereszkiewicz), who arrives mysteriously, like Mary Poppins—if Mary Poppins were a sexually liberated Gen Zer who wears sparkly roller skates and candy necklaces, and has magical baby-whispering abilities. She fascinates Nadine—and unabashedly reflects the couple’s long-squelched desires and sexual hangups back at them.

The self-absorbed male characters are more cartoon-like and less interesting than Chokri’s numbed housewife and Tereszkiewicz’s hilariously blithe babysitter. At times, the manic banter can be exhausting. But Chokri has an exhilarating visual style—think kitschy pops of emerald and scarlet—that catapults all of this into the surreal: one scene of Cédric, at a parent-and-baby swimtime in a pool full of floating red balls, looks like a wild dream. Or, like the rest of the film, a suburban nightmare.

IF THE MESSAGES about sex and gender aren’t always easy to read in Babysitter, wait till you experience That Kind of Summer.

“You are not forbidden any sexual thoughts or behaviour here. You are not sick,” an unconventional therapist tells three female sex addicts who have gathered at a lakeside retreat to quell their paraphilia. And so opens Denis Côté’s defiantly nonjudgmental look at sexual obsession, although just what he’s trying to say about the trio, and their caretakers, feels elusive—and possibly problematic.

The prolific Quebec director shoots in uneasy closeup as we get to know the women. Geisha (Aude Mathieu), a sex worker with a lip piercing and shaved head, is an exhibitionist who feeds off male attention and the power she wields attracting it; Léonie (Larissa Corriveau) works through sexual trauma in her past by submitting to humiliation, often with strangers; and when Eugénie (Laure Giappicon) isn’t obsessively masturbating, she’s working through her issues via charcoal drawings.

The performances are strong across the board. Corriveau hands in an extended, uncut monologue recounting a degrading gang bang with a mix of melancholy, matter-of-factness, and inner strength; listen to the painful details of a construction site’s bare light bulb being being turned off. And Mathieu is as magnetic as she is reckless and rebellious.

It’s when the women take off on 24-hour leave that we really see the full scope of their problems, as they plunge back into their bad habits.

Côté fills the film with frank scenes of full frontal nudity and sexual exploration, though he’s careful not to exploit; in one scene where Geisha decides to pleasure an entire soccer team, we’re mostly left to imagine what happens when she leads its members into the trees. Still, tonally, the film sometimes feels like it’s treating the women’s self-destructive tendencies with unsettling indifference—filtered through a male gaze.

The “therapy” is far-fetched—just who is paying for the treatment, and its goals, are hard to discern. The point seems to be that because the women’s behaviour defies the therapist’s academic theory, it needs to be accepted in a way that doesn’t carry gender expectations or shame.

Still, there is at least a hint that the women are starting to have fun, even jumping in the lake, and learning “a way to be other than through sex”, as their therapist encourages. Yet visiting German counsellor Octavia (Anne Ratte-Polle) largely admits defeat. Other than that, Côté seems satisfied to shock, provoke, and leave us to our own complicated conclusions.