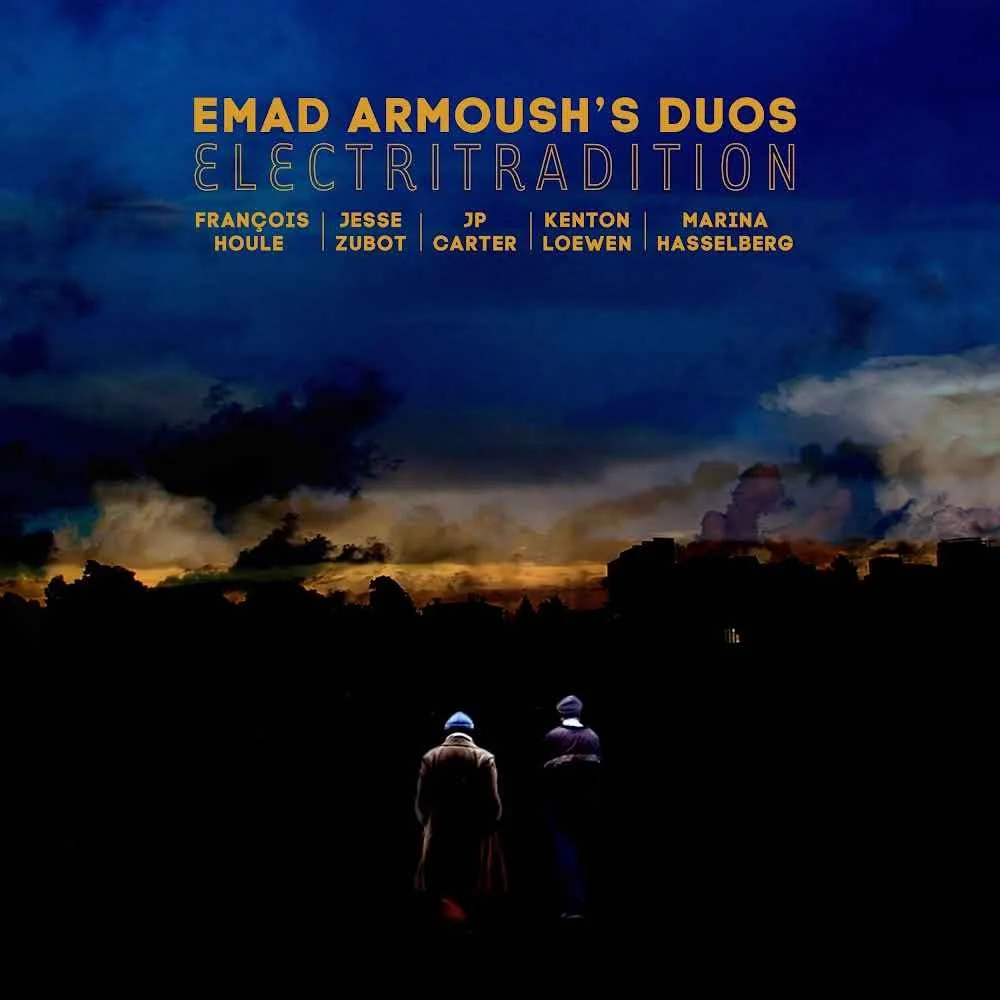

On the new album Electritradition, Emad Armoush's Duos project explores exile, community, and how to live in a war-torn world

Syrian-born singer and musician performs otherworldly duets with Jesse Zubot, François Houle, Marina Hasselberg, Kenton Loewen, and JP Carter

Emad Armoush

Emad Armoush and Rayhan host a release party for Electritradition at Tyrant Studios (1019 Seymour Street) on Friday, September 29. For tickets visit www.tyrantstudios.com

GIVEN THE PRESENCE of an all-star cast of improv and new-music virtuosos, one would expect Emad Armoush’s new album of duets, Electritradition, to be primarily an instrumental showcase—and you wouldn’t be entirely wrong.

After all, Armoush—a Syrian-Canadian who grew up with Arabic music and later became a skilled flamenco performer—is himself no slouch on oud, classical guitar, and the Middle Eastern cane flute known as the ney. But what initially catches the ear with Electritradition are the songs, some traditional, some self-composed, and one a perennial staple of Arabic music since the 1970s.

Armoush wisely starts his follow-up to last year’s full-band Fragrance with the latter. “Ya Rayah”, written in 1973 by the Algerian musical innovator Dahmane El Harrachi, sets the tone for the whole album with an indelible melody and words that express the longing of exile, haunted by what they have left behind but aware of the necessity of change. Using his own dark-hued oud and the breathy, electronically assisted clarinet of François Houle, Armoush immediately establishes that we are entering a liminal space, with familiar melodic elements floating in a wash of abstract sound. His vocals don’t enter until the last minute, and he sings only a single verse, but within that span he reveals his own strength, nostalgia, and profound musicality.

As the vocalist for Gordon Grdina’s wildly creative avant-Arabic big band Haram, Armoush has already established himself as British Columbia’s most visible ambassador for Arabic singing, and what most distinguishes that style is how it differs from North American norms. In North American rock and pop, at least, male singers often limit themselves to three main modes of expression: pleading, boasting, and bullying. Arabic singers allow themselves more dignity, or so it seems from the outside, especially when tackling serious matters such as exile, community, and how to live in a war-torn world.

That last, perhaps unsurprisingly, is the topic of “Warrior’s Dance”, the second track on Electritradition. Musically, it follows a similar path to “Ya Rayah”, with Jesse Zubot’s moody violin harmonics providing an atmospheric bed for Armoush’s nylon-strung guitar. The lyrical plot differs, though: in “Warrior’s Dance”, the singer establishes a dialogue between two Arabs, switching between his native Syrian accent and an Iraqi mode of speech as his protagonists trade observations on their beautiful and afflicted homelands.

“I’m trying to do—and I do it more in Haram, now—kind of a rap feel,” Armoush explains. “This verse, here, is trying to explain the existential problem of the world. Well, not explain, but it’s two people talking, kind of in an Arabic colloquial approach, and one guy is telling the other guy ‘There is a worldly problem here that kind of has no solution.’ And the other guy is saying ‘What?’”

Do the two reach any kind of resolution?

“No,” Armoush allows. “I’m trying to state, in Arabic at least, that there is no present solution for that problem. Not a permanent solution.”

These serious questions demand a serious approach, but Armoush contends that if his voice sounds especially rich and committed on Electritradition, at least some of the credit should go to recording engineer John Raham and his Afterlife studio. “When you’re recording with great microphones—which I was surrounded by, thanks to John—then you hear everything,” he says. “So I was able to be more musical because I could hear what I wanted to go for.”

But he also points out that Arabic singing stresses the integration of technical virtuosity and emotional depth. “You’ve got to put some juice into it,” he explains. “You can’t just be concerned with perfect pitch, or having a good timbre; you still have to put emotion into it. Like, there’s so much feeling when you’re the singer, but because you modulate vocally you have to stay focused. You can’t just let go into the emotion of the lyrics. Maybe that’s part of it.

“The whole thing of tarab is that when everything is resonating and the pitch is perfect and this thing is building then you can explore, and everything will sound good,” he continues, referring to the Arab concept of inducing a kind of ecstasy through disciplined beauty. “They can actually take more chances and they will still sound good because they build on a whole bunch of rules that nobody is ignorant of. They’re not just jiving.”

And neither, it is clear, are Armoush’s guests on Electritradition, who in addition to Zubot and Houle include cellist Marina Hasselberg, trumpeter JP Carter, and drummer Kenton Loewen, Some have made their own studies of Middle Eastern music, either on their own or through playing with Armoush in Haram and his own band Rayhan, but they’re all deeply attuned to his musical goals and have their own highly expressive voices. Collectively, their sound is both earthy and otherworldly—and for them all, it’s home.