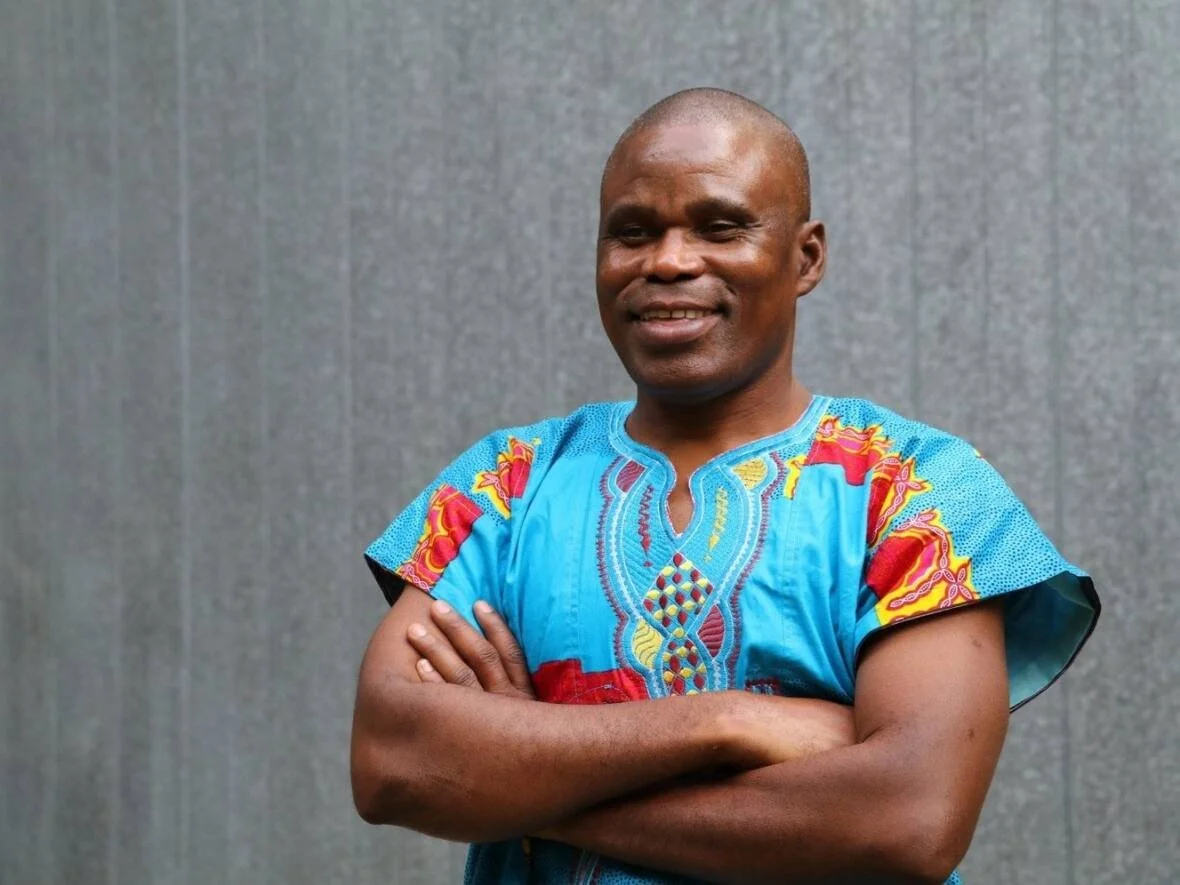

Pianist-composer Aaron Diehl blurs boundaries between jazz and classical

Spotlighting ragtime and Harlem stride at the Chan Centre, New York City musician pushes beyond limitations of easily marketable categories

Aaron Diehl. Photo by Evelyn Freja

Chan Centre for the Performing Arts presents American pianist-composer Aaron Diehl in a Chan Shun Concert Hall show programmed by David Fung on April 19 at 8 pm.

WHEN STIR REACHES Aaron Diehl in New York City, the pianist is only too happy to share some of what he’s got on his calendar over the coming months—and much of it, as it turns out, has a Vancouver connection.

For instance, Diehl will be taking over Bill Charlap’s post as artistic director of the 92nd Street Y’s Jazz in July series. Saskatchewan-born and North Van-raised pianist Rene Rosnes is a regular on New York’s Jazz in July program; she also happens to be Charlap’s wife and frequent musical collaborator.

Next month, Diehl will team up with Vancouver-born Vicki Chow—a member of the Bang on a Can All-Stars and a solo-piano powerhouse in her own right—for a performance of Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians.

“There’s a lot of great musicians from Vancouver,” says Diehl, reached as he’s prepping for a performance at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Darcy James Argue is another one, who I’m collaborating with for next year. He’s writing some pieces for me, and potentially my trio. That hasn’t really been announced yet, but that’s definitely on the docket.”

Before any of that, Diehl will be in Vancouver himself, playing a concert that will focus on ragtime and Harlem stride, two styles of music that were key elements in the early development of jazz. Think James P. Johnson, Fats Waller, Willie “the Lion” Smith, Jelly Roll Morton, and Mary Lou Williams.

Diehl has a particular affinity for the music of Williams. Last year, he released a Grammy-nominated recording of her Zodiac Suite. Williams first conceived of the set of 12 pieces—each inspired by an astrological sign—in 1942, premiering it in a live broadcast on radio station WNEW in ’45. In truth, she had only completed three of the pieces in time for the broadcast, and ended up improvising the other nine live on the air.

Williams had finished composing the suite enough to play it with a chamber-jazz group at New York's Town Hall later that year, following that up with a June 1946 performance featuring a 70-member symphony orchestra at Carnegie Hall.

To hear Diehl tell it, however, Williams was in some ways still making the thing up as she went. “Yes, there are certainly stretches within Zodiac Suite that were initially improvised and then became written, but even within that written material there are variations that she made depending on the performance,” he says.

Diehl got to know Peter O’Brien—who was both a Jesuit priest and Williams’s manager—first as a student at Juilliard and later through his involvement in the music program of a predominantly Black Catholic church in Harlem.

It was through O’Brien, who passed away in 2015, that Diehl acquired his deep appreciation of Williams’s work—and the score for the Zodiac Suite.

“Fortunately, thanks to the work of Father O’Brien, it was published before her passing, but there were still a lot of issues with the arrangement; copying issues that were present with the original manuscript,” Diehl says. “During the pandemic, just as a project, given that there wasn’t much going on in terms of actual performing, I decided to actually take on seeing that this arrangement could be played, and eventually collaborated with the Knights orchestra in order to do that and record it.

“So it’s been a wonderful journey over the last four years or so, being able to present this work, and there being interest,” the pianist continues. “When I started it, certainly in the orchestral world people really weren’t familiar with it, and it was an imperfect score. There are still some issues; there are some question marks about the orchestration and what she intended, yada yada yada. But I think over time, people caught on, caught interest in the work. In fact, we’re doing it with the BBC Scottish [Symphony] Orchestra at the BBC Proms in August, so that’s very exciting.”

Photo by Maria Jarzyna

In some ways, Williams’s work as a performer and composer, whose music didn’t always fit neatly into ready-made categories, predicted Diehl’s own career. There was certainly precedent for the cross-pollination of jazz and classical; George Gershwin, for one, was doing it as far back as 1924 with Rhapsody in Blue, and Duke Ellington was moving into film scores and extended compositions in the ’30s.

A century or so on, however, the divisions remain entrenched in many listeners’ minds. In a 2023 profile of Diehl, Stereogum’s Phil Freeman wrote that the pianist has “one foot in classical and the other in jazz”—which suggests that he is straddling two distinct musical worlds rather than truly fusing them into what Gunther Schuller called a “third stream”.

“Someone I really admire and am quite in awe of is Tyshawn Sorey, who is a wonderful composer and percussionist and trombonist and pianist—a multi-instrumentalist—and he has a way of seeing music that isn’t restricted by the marketing limitations of these descriptors,” Diehl says. “I think many times when we’re talking about jazz or classical, it’s more in terms of how these things can be marketed to a certain kind of audience, and what I’m interested in doing throughout my own existence on Earth is to continue developing a certain set of skills as a musician, and to be able to find ways to employ those skills in an effective and concise way of communicating.

“Of course, culturally, there are very defined traditions,” he adds, “and I think it’s very important to respect and reference and understand the depth of certain traditions, but at that point it’s how a musician takes those elements and creates something that can be very unique and special.”

In the case of melding the jazz and classical traditions, Diehl says that the challenge lies in “how to have the fundamentals of what is so important and essential in the Black American music genre, but also have the beauty, the colour, and all of the nuances of the orchestral environment involved. That’s always very, very tricky. Not because it’s impossible, but because the foundation, the background of the musicians is so different.”

Diehl does, however, see this changing each year, observing that younger players coming up now are more open to adopting an approach to music that incorporates elements of different genres and styles.

“That’s a very positive attribute to have,” Diehl observes. “It can make for some very interesting and fulfilling conversations, musically.” ![]()