Vancouver filmmakers put epic effort into queer-refugee-sponsorship tale Someone Like Me, at DOXA

Directing duo Sean Horlor and Steve J. Adams followed every aspect of their subjects’ lives—right into a pandemic

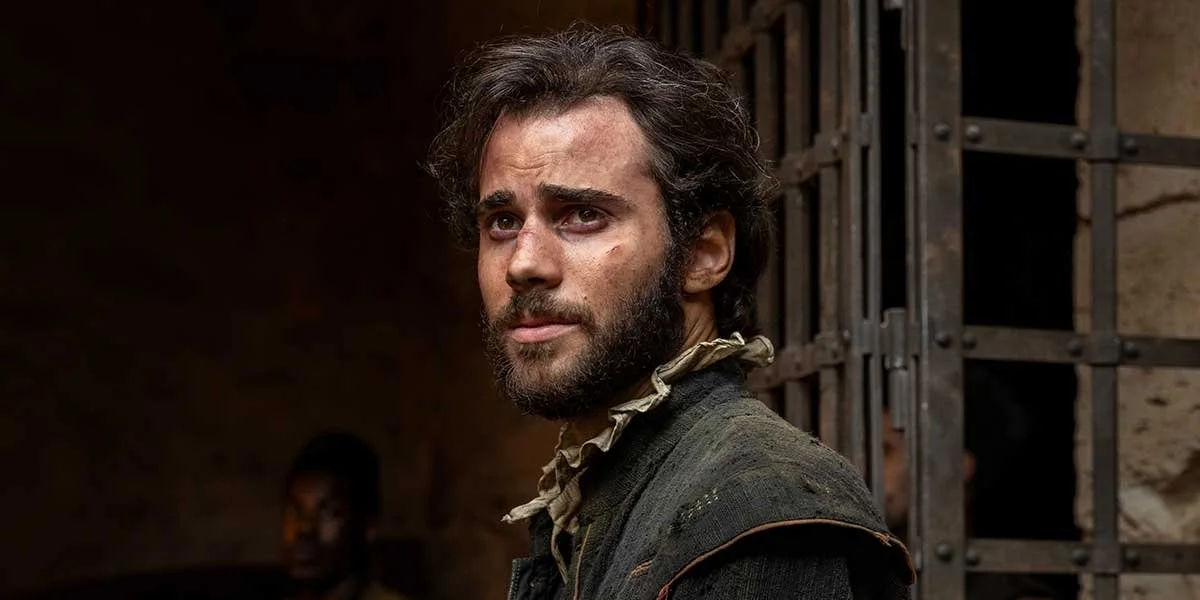

Drake, a Ugandan refugee, in Someone Like Me.

Filmmakers Steve J. Adams and Sean Horlor

DOXA Documentary Film Festival streams Someone Like Me, part of the Rated Y for Youth Program, from May 6 to 16

FILMING SOMEONE Like Me, about a group of Vancouverites who sponsor a gay asylum seeker, was already going to be a challenging project for directors Sean Horlor and Steve J. Adams.

And then, roughly seven months into their intimate, yearlong shoot, a pandemic hit.

“We were freaking out,” Adams tells Stir, able to laugh about it now with his partner on speaker phone, in the days before the NFB film’s debut at DOXA Documentary Film Festival. “The agreement was that we were going to spend 12 months filming everyone. And now no one was allowed out!”

The solution? The iPhone 11 Pro—a device that ended up making the film an even more up-close-and-personal experience than it already was. Consider it a testament to this directing duo’s adaptability and strength—honed over years of filming, including the short doc “Brunch Queen” about the storied Elbow Room Café and the musical based on it. But it also shows the resilience of Someone Like Me’s subjects, especially a 22-year-old newcomer from Uganda, by way of Kenya.

First, let’s back up a bit, though.

Horlor and Adams had been researching their subject for a few years. They sat in on several sponsor groups at Rainbow Refugee, a community organization founded in 2000. The nonprofit supports people seeking refugee protection in Canada due to persecution based on sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, or HIV status. The filmmakers saw the program as a unique chance to portray the queer community in all its diversity. The subject would also allow an inside look at Canada’s sponsor-based refugee system—its empathy and volunteer commitment, but the bumps it can experience along the way as well.

“We really wanted to tell a story about the queer community and what was happening in it right now,” Horlor relates. “When we saw Rainbow Refugee doing the important work they're doing and bringing together 10 people who didn’t know each other, we knew there would be some interesting stories.”

Adams adds that what struck them sitting in on initial sponsor groups was the diversity of the LGBTQ2SIA community working together and sharing skills to bring someone in from overseas. “It was one of those rare moments where there was someone from the trans community, someone who’s lesbian, someone who’s gay, and seeing that it’s not this monolithic worldview,” he explains.

But their research also made them all too aware of the variables at stake if they wanted to track a sponsorship from start to finish.

First, they would have to embed themselves with a group of about 10 refugee sponsors who hadn’t ever met each other before their first meeting. On top of that, there was no way to predict who the sponsored refugee would be or where they’d be from. Or even whether that person would want to be filmed at all.

“There are over 70 countries in the world where you can be imprisoned or murdered for being gay—he could have been from Russia, the Middle East, or somewhere else,” says Adams.

The sponsorship group meets at Rainbow Refugee in Someone Like Me.

In one tense scene that reveals the heavy responsibility on the sponsorship group, they have to agree on who to sponsor—weighing age, career aspirations, and level of persecution. It drives home how many are left behind in dangerous situations around the world.

Fortunately for Horlor and Adams, the sponsors chose Drake, an aspiring fashion designer who loves music, and who also happens to be comfortable in front of the camera.

“Back in Nairobi he was doing podcasts and doing a lot of work for people within the HIV community, so when he saw what we were doing he recognized what we were trying to do,” Horlor says.

That act of generosity helped a lot. But Horlor and Adams ended up juggling not only his storyline, but those of the sponsors—including one person whose gender transition would beautifully echo Drake’s own quest for freedom to live his life. Even before the pandemic, that meant booking crews for multiple households to capture the unfolding stories in vérité style, writing the script as they went.

The Someone Like Me crew at work. Photo courtesy Steve J. Adams and Sean Horlor

Adding to the grey hairs that Adams swears he acquired during the shoot, the sponsor group started to fracture, dealing with disagreements over Drake’s path, also documented in the film. “The emotions were so high. We went through some stuff for sure,” he says.

Now throw pandemic shutdown in the mix, right around the time the hard reality of resettling in Canada is starting to hit home with Drake. “About six months in, you’re in a brand new country and starting from scratch, and you're realizing everything you gave up,” Adams says.

“Drake arrived here and they all had all these hopes and dreams for the first 12 months,” Horlor elaborates. “He wanted to be in fashion school or work on a film set. But with the pandemic, everything he planned for, and everything we planned for, is turned upside down.” He points out Drake’s ability to deal with those obstacles shows how strong he is.

Faced with early-pandemic lockdown, the film team came up with a system of delivering an iPhone to each subject’s household. “We sent out questions and left a phone with them, then would pick it up and sanitize it,” Horlor explains. “And it turned out to be some of the most intimate footage we got. We were really happy when we got the footage.

“Drake would usually film himself between midnight and four in the morning—he was still living on Ugandan time!” he adds with a laugh.

What got the team through was a sense of humour and a close bond that they formed with their subjects both during and outside of the shoot.

“We spent so much time with all these people with no cameras rolling,” Horlor reflects. “With Drake, we spent as many days taking him around and showing him the city as we did shooting him. And so we got ourselves through the pandemic with this unexpected joy that came from that.”

Horlor and Adams came to understand resettlement for refugees as a more complex process than they did going in—but still thoroughly worthwhile.

“One of our biggest takeaways was, How do you really support somebody? How do you support somebody’s autonomy?” Horlor says. “And those lessons in the film carry over to helping a family member—they’re life skills. I hope that for people the takeaway is that you can love and care about them without trying to save them and control them.”

“Even with all the bumps, Drake is here and he’s safe,” Adams adds. “He’s healthy and he's continuing on with his life. He doesn't have to worry about being hurt. By those measures it is a success.”