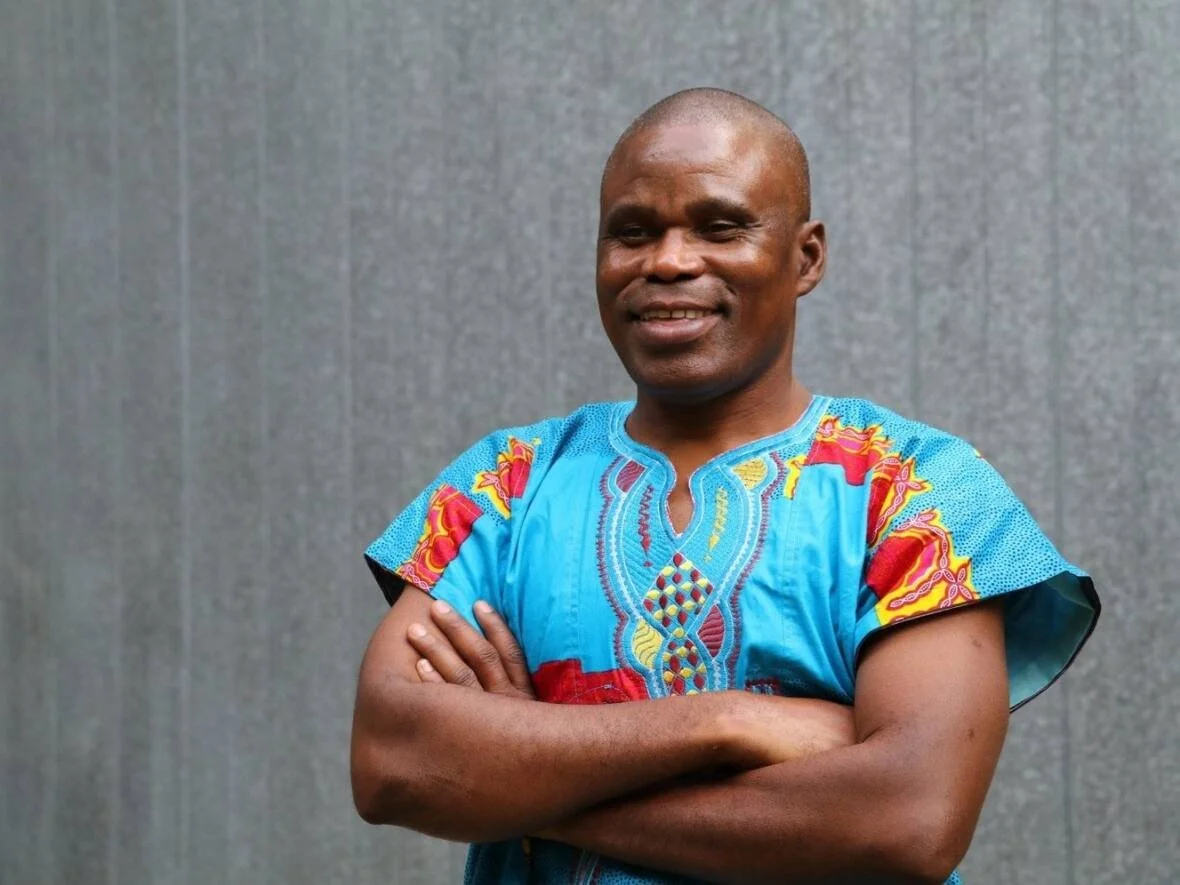

Pianist Tomasz Ritter brings his passion for period instruments to Vancouver Chopin Society

Polish star will play Beethoven, Schubert, and, of course, Chopin on a faithful copy of an 1819 Conrad Graf piano

Poland’s Tomasz Ritter will play a host of classical and romantic composers in ways you may have never heard them before—and may never hear them the same way again.

The Vancouver Chopin Society presents Tomasz Ritter at the Vancouver Playhouse at 3 p.m. on April 16

TIME TRAVEL IS POSSIBLE—but not, so far, through artificial intelligence, reverse-engineered alien technology, or super-secret advances in quantum physics. Instead, all you need is a vintage piano.

Even a faithful copy of one will do, as Poland’s Tomasz Ritter will demonstrate when he performs a matinee recital at the Vancouver Playhouse, as part of the Vancouver Chopin Society’s ongoing concert series. Recognizing Ritter’s rising popularity as an advocate of historical performance, the Chopin Society has arranged for the use of Early Music Vancouver’s Paul McNulty piano, a faithful copy of a Conrad Graf instrument from 1819, and the young musician has tailored his program accordingly.

Most notably, he’ll be performing two of the great masterworks of early-19th-century piano literature: Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 30 in E major and Franz Schubert’s Piano Sonata in A minor. These, Ritter reports in a telephone conversation from his home, will be the “main points of gravity” in a recital that’s fleshed out by works from Johann Sebastian Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and, of course, his Polish countryman Frédéric Chopin. It’s entirely possible that you will have never heard them as Ritter intends to play them, and you may never hear them the same way again.

“I was, I think, 11 when for the first time I tried a piano from Mozart’s era, and of course I hadn’t studied historical instruments at this point, but I knew that something like this existed,” the 28-year-old, Lublin-born keyboardist explains. “It was something that I immediately found very interesting, and so from the age of 11 I practised modern piano as my main thing, but I had some regular contact at summer master classes and so on with historical instruments.”

More recently, understanding the genesis of classical and romantic music through period-correct instruments has become Ritter’s passion. He’ll happily discuss, articulately and at length, how the rapid evolution of the piano between the end of the 18th century and the middle of the 19th gave rise to new and ever-more-complex writing for the instrument, and how modern pianos tend to obscure some of the characteristics of earlier music.

“First of all, I think. historical pianos demand different things from you, because you cannot simply play like you are used to on the modern piano,” he says. “Of course, you notice very quickly that some things you simply cannot do on a period piano. You cannot play that loud, you cannot play that heavily, you cannot play with such balance between right and left hands. But as you adjust your technique and adjust your ear for listening differently, you start to realize that the texts that you know—from Mozart, from Haydn, from Beethoven, and so on—make much more sense than on the modern piano. Basically the historical piano is a tool, like a translator for this language. For these languages, actually, because each composer had his own approach.

“In general it opens your ears, let’s say, so that you start to look for new sounds that maybe you didn’t hear before,” he continues. “For me, this is the most intriguing and interesting part: the imagining of something different. You can widen your range of things that are possible to play.”

Ritter points out that the way the modern piano is constructed—with long bass strings crossing over the treble strings rather than running parallel to them—makes a much more powerful sound, but somewhat muddies the clarity of the middle register.

“In Mozart, for example, you have a lot of articulation: a lot of slurs, a lot of dots and so on, and a lot of these slurs are like words that you have to pronounce,” he explains. “And with the very deep and long sound of the Steinway piano you cannot pronounce them as quickly, as expressively….The shorter sounds of a Stein or a Walter piano, they automatically give you this speaking way of playing which is very important in Mozart’s music.”

Performing Mozart on a Graf-style instrument, Ritter admits, is something of a compromise, although a Graf is closer to what the Austrian wunderkind would have known than it is to a modern Fazioli or Bösendorfer. McNulty’s Graf copy, however, is not much different than the instruments that Beethoven and Schubert would have owned; in fact, Graf built the piano that Beethoven preferred towards the end of his life, lengthening the keyboard and striving for louder and more penetrating sound.

“This is the deaf Beethoven already, the Beethoven that tries to bring the most from the instrument,” Ritter says of the Piano Sonata No. 30 in E major. “This is actually interesting to do on this instrument that he knew. And this is an interesting topic: with the pianos that were made exactly for Beethoven, the instruments had to have some special amplifiers, some devices that helped him listen, you know. You can notice that on such Graf pianos; he uses all of the resonance that the instrument gives him.”

Schubert might not have had such direct impact on the development of piano technology, but Ritter sees Beethoven’s 1820 composition as a direct precursor to the younger musician’s 1823 masterpiece, which will end his concert on a dark but undeniably impassioned note.

“This is a piece that I’ve played for some time and I really love it, so I thought that I would include it,” he says. “Like many Schubert pieces, it is quite… frightening, let’s say. There is this fear of death in it, probably. There are a lot of darker colours, and it also brings out the darker character of this Graf piano.”

There’s nothing to fear here, however. Given the presenter, there’s a very good possibility that Ritter’s encore will include some sprightly Chopin, and Sunday afternoon should end with uplift rather than with Schubert’s beautiful gloom.