Artist Alan Storey plays with time, space, and motion under the ever-swinging Pendulum

Exhibition marks a new fertile creative period, with pieces on a smaller scale than his well-known public works

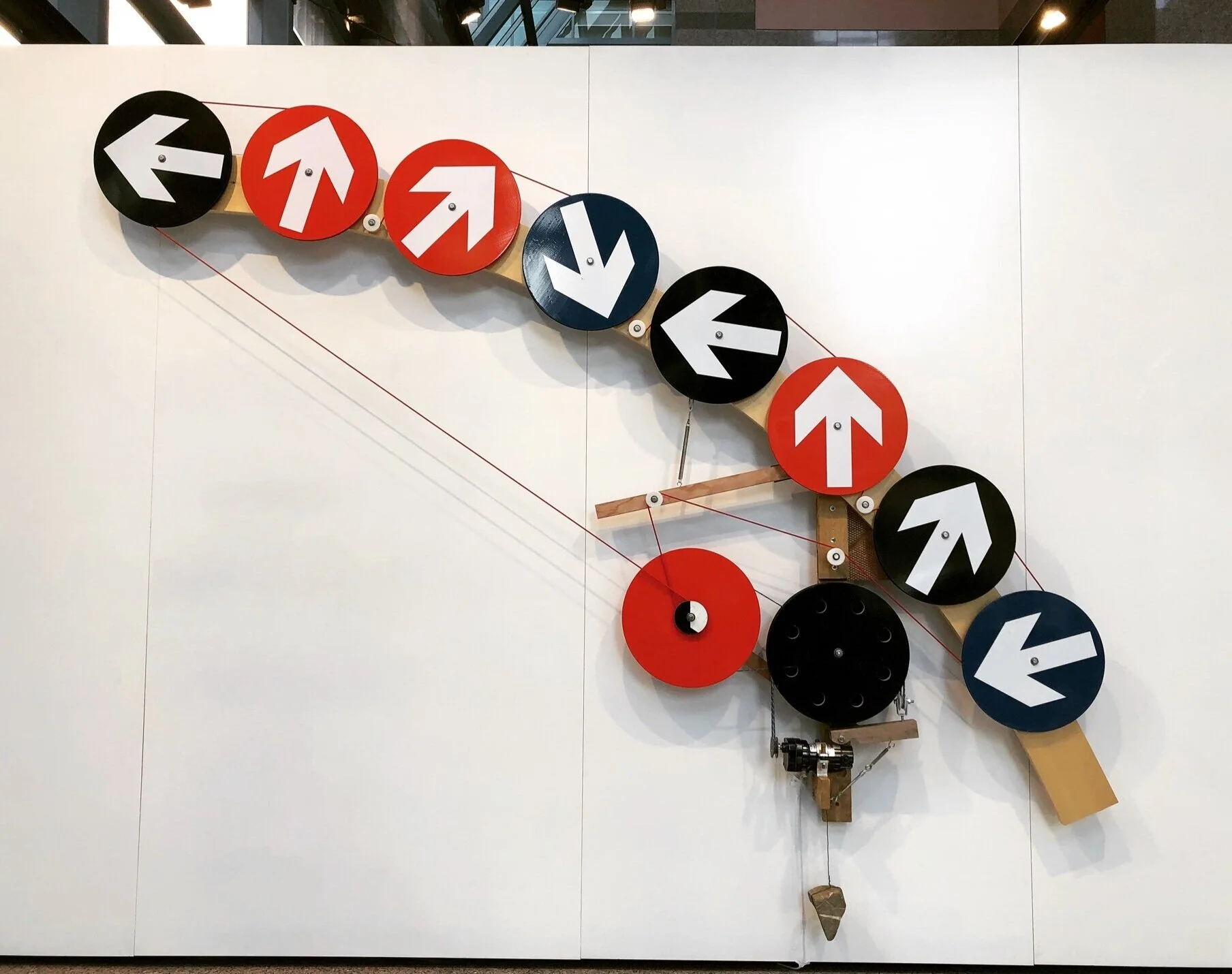

Convergence, inspired by a traumatic incident and constructed from ski-lift and -sign parts (2017), from the exhibit Some Moments in this Time and Place.

Alan Storey stands under his iconic Broken Column. Photo by Dina Goldstein

Alan Storey: Some Moments in this Time and Place shows at the Pendulum Gallery until September 17.

AS THE CREATOR of the monumental pendulum that swings in the atrium of the HSBC building on Georgia Street, Alan Storey is one of the biggest names in public art in the city.

He’s the mind behind the steam-activated wooden barrels of Coopers Mews on False Creek; the hypnotic Oscilloscope-like LED screens on the Mount Pleasant BC Hydro Sub Station; and the nautically inspired Compass that runs the entire height of Bellevue, Washington’s City Hall.

Storey has a knack for thinking big—and being able to execute the mechanics of those ambitious ideas. Think of the gigantic drawing machine that once tracked a Ballet BC dancer’s motions on the Queen Elizabeth Stage.

And so it’s telling that even he has not been immune to the terrible squeeze put on artists in this city’s real-estate and gentrification crisis.

It’s important to note that there is a happy ending to all this. After several years of upheaval, the artist has his first solo exhibition in 15 years here, and it floods with exciting ideas that meld the complexities of the cosmos—relativity, quantum mechanics—into playful, relatable pieces, on a smaller human scale than his public artworks.

Titled Some Moments in This Time and Place, the exhibit includes a horizontal, clocklike dial that orbits to the rhythm of sine waves; a drawing created from a machine responding to wind, temperature, and rainfall; and an espresso pot that percolates a ball chain into a vast, starburst-shaped void.

They are at once fun and profound. If you’re in a certain headspace, they will definitely prompt thoughts of mortality and our place in the universe. And they all sit in the shadow of Broken Column, the 1987 pendulum, suspended from the atrium’s glass ceiling, that slowly ticks away the time.

Today, perhaps because of this pandemic moment of a grand, global pause, the pendulum seems as resonant as it was when it was erected 34 years ago. “That’s been a pleasant surprise,” Storey comments to Stir, admitting he worried about what its lasting relevance would be at the time he designed it, “especially in terms of the context of the architectural and social dynamic of the space.”

Space to create

To understand what brought Storey to this new fertile creation period of smaller works, it’s first important to back up to 2016. That’s when he was evicted from the 2,800-square-foot space at 339 Railway Avenue where he had spent 32 years. The landlord wanted to renovate the building to re-rent it at higher rates.

Storey has always worked on a large scale and requires the industrial equipment and materials to do so. And so, when he couldn’t find an affordable, big-enough studio, he ended up having to store his belongings, accumulated over the decades, into shipping containers.

Here’s how he recounted his efforts in a written piece for an Eastside Culture Crawl show devoted to the artist-displacement crisis:

What didn’t go into shipping containers went into the dumpsters. It was cathartic. I parked the containers in an unused Turkey Farm in South Langley and I left town for four months. At this time I considered leaving Vancouver all together. Upon return, I spent another six months looking for space and finally found something workable for reasonable rent in New Westminster. It took another year to repair and renovate the space to make it functional as workshop with all my tools.

What happened next? Storey was evicted again from the New West space.

But things finally worked out. Today he is comfortably settled into what used to be a friend’s old shipbuilding quarters in Richmond. At the same time, after years of running a business helping other artists fabricate their work, he’s refocusing on making his own pieces. And he’s finding his voice again.

“I sort of got swallowed up into making other people’s work for a number of years,” he says. “I’m making a concerted effort to make my own work now and it’s a great feeling.”

M Theory (with coffee pot)

Random fate and connection

One of the key pieces in the new exhibit emerged from the years of eviction and turmoil. Called Convergence, it features at-first-cheery-seeming black, red, and blue ski-sign arrows that move slowly on wheels. Their system of pulleys is weighed down at the bottom by a rock, akin to gondola mechanics. The arrows point in all different directions, but every five days to a week, all of them synchronize for a single turn.

Convergence was created at an artists’ residency in Austria’s mountaintop SivrettAtelier, where Storey headed, disoriented and worried about the future, after losing his Railtown space. He connected immediately with the seven other participants, in particular an affable Austrian artist. Tragically, during a mountain hike, that colleague died of heart failure in front of the other artists—as Storey recounts it, while laughing hard. The traumatized group, who bonded tightly in the days afterward, decided to continue the remaining two weeks of the residency in the artist’s honour. Convergence emerged from that time of research, Storey studying the workings of the gondolas, finding the discarded ski-hill signage, and mulling over the randomness of the universe.

“I had played around for years with the notion of things going in and out of phase and in and out of patterns, and I just created this device based on the gondola system,” he says. “They [the arrows] converge for that one moment, and the rock at the bottom is the tension to balance the whole thing.” The work expresses the idea of the artists connecting over that blip in time, but also larger ideas of how people’s lives can synchronize and then roll apart again.

Salvage and reuse

There are other personal touchstones from over his career in Storey’s works in the Pendulum Gallery exhibit, many the kind of salvaged or recycled materials he has long employed.

M Theory (with coffee pot), reworked from 2012, models debates around string theory, relativity, and gravity with a simple espresso pot that percolates an endlessly looping ball chain that disappears into a “black hole”. “The coffee pot is where people sit around discussing ideas,” he summarizes, “and those are little loops of ideas that go into the black hole.”

Point of Origin

Point of Origin integrates a centuries-old piece of Douglas Fir timber that Storey salvaged from a wharf being dismantled to make way for Expo 86. He first exhibited it in the legendary October Show of the mid-’80s, running it like a post up through three floors of the building for the art exhibition. He later displayed it as part of an installation in Banff, and then used the beam as a work bench in his studio before dismantling it. For the piece here, he pulls the beauty out of the wood, carving down to the centre of the annual rings and fitting it with a gramophone-like aluminum horn; in the “black hole” of its bottom, a wire twitches on the second-hand axel of a clock. Here the dichotomy of Storey’s work is on full display: a whimsically shaped object that invites you to stare deep into the abyss of time and space.

Elsewhere, the unassuming Here Here reflects on 50 years of Storey’s life and work. Amid its reused pieces, it features an ore-crushing ball he collected in 1970 when he was 10, a motor salvaged in the mid-’80s, and a shell found on the west coast of France in the 1990s—its shape echoing the spiral motion of the piece.

“I have too much stuff in my studio,” Storey says, laughing that he’s been creating works to use some of it up.

Storey traces much of his interest in building, tinkering, and science to his father—a math and physics teacher, musician, and builder of boats and even their family home.

Storey is trained as an artist—he holds a BFA major in sculpture from the University of Victoria—but those practical roots are perhaps what lend his works their accessibility and lack of pretension.

Even when they stand on the still-awe-inspiring scale of Broken Column.

“I don’t try to obscure anything in art jargon,” he offers, explaining it’s not important for his viewers to read didactic panels for the background of his works. “There’s a beauty to the time pieces where you don’t have to know that to understand them. People can find them interesting in terms of engineering, in terms of the mechanical aspects of it. There are a lot of entry points.”