In Polygon Gallery's Miradas Alternas, five Mexican artists find new ways to look at absence, loss, and femicide

Photo and video works use abandoned roadstops, graffiti, and more to make sense of violence

Juliana Alvarado, Flaka, From the series Name Them, 2017, Inkjet print

The Polygon Gallery presents Miradas Alternas until February 7, 2021. See COVID-19 safety protocols here

NINE PHOTOGRAPHS of derelict, sherbet-coloured buildings sit in a perfect grid on the walls of the Polygon Gallery’s new Miradas Alternas: Through Her Lens exhibit. Each abandoned diner is framed identically, alone in the landscape, a dusty road in the foreground and a blindingly blue desert sky in the background. Every one is named after a woman: “Cafe Estrella”, “Cafe La Flaka”.

Juliana Alvarado’s Name Them goes far beyond the simple documenting of desolate roadstops in Mexico’s Durango region. Like the other photo- and video-based works in the new exhibit Miradas Alternas: Through Her Lens, it’s about absence, oppression, and loss. It uses images to explore the way a society can neglect and abandon women, as well as prescribe roles.

“What I was interested in was the way she is using language—the gendered role around women in Mexico around hospitality, but also in the metaphorical way she uses architecture,” curator Andrea Sánchez Ibarrola tells Stir on a Zoom call from Mexico City, where she’s spending pandemic lockdown. “It really does represent what you would see on a long road trip in Mexico.”

For Ibarrola, who recently completed her Masters in critical and curatorial studies at UBC, the thought-provoking new exhibit has become a way for her to personally work through the violence that has ravaged her home country over the past two decades—particularly femicide and the disappearance of women.

Sonia Madrigal’s photograph from the series Death Rises in the East, ongoing since 2014.

“I didn’t realize at the time I was working on it, but now I see it was my way of making sense of things,” she says. “It was about understanding but also about feeling that there’s something I can do.”

The exhibit is in part a response to the media saturation on the subject of violence against women in Mexico. That saturation includes not just the widely covered murders of hundreds of maquila workers in the border cities like Ciudad Juárez in the 1990s and early 2000s, but those in an ever-shifting array of other states where drug violence is also a fact of life.

The Centre for Strategic & International Studies estimates that 10 women are killed every day in Mexico, and that the rate of femicide has doubled in the last five years.

It’s an issue that came into relief when Ibarrola arrived here to pursue her MA. “When I came to Vancouver I realized there was a different way that I was feeling; I felt safe being in the city without having the dread of walking home,” she reflects. “I noticed a considerable decrease in my stress and anxiety.”

Later, though, she found out about missing and murdered Indigenous women in BC, and the issues of sex work, housing, and addiction in the Downtown Eastside. “That made me question about how violence is pervasive in all societies,” she says.

As Ibarrola went back to Mexico to start researching the project in the summer of 2019, she was drawn to photographic images that offered an alternative to the more exploitive depictions seen in the news there. There was something disturbing about the way the bodies of murdered women were shown online and in print, compared with those of male victims. “The images of femicide were sexualized and very explicit,” she says, adding photojournalism has traditionally been a male-dominated field.

There were also tropes around the way their stories were sensationalized in media coverage after their deaths, Ibarrola points out. Often, newspaper, web, and social-media images would show pictures of women and girls’ empty bedrooms, or picture the parents’ hands clasped in grief.

What Ibarrola discovered was a wave of Mexican women artists using photography to represent the issue with an “alternate gaze”, which is the meaning behind the show’s Spanish title “Miradas Alternas”. The Polygon exhibit features five compelling voices in lens-based art from that country.

“It was photography looking for different ways to represent absence and loss, without retraumatizing images,” she says, “How do you represent someone who is now gone? There is this phenomenon of the disappeared body, and it’s a social and political and economic one. The war on drugs has had a terrible toll in the amount of deaths but also in the disappeared….I was interested in alternative languages to represent that.”

Echoing the emptiness of Alvarado’s roadside diner shots is artist Koral Carballo’s haunting “At the Wrong Time” series. The inkjet prints capture nighttime urban streetscapes in Veracruz, a city under curfews due to criminal gang activity. Bathed in the ugly orange glow of mercury street lights, sidewalks, roads, and apartment walkways sit unused by civilians in fear. “It was a time when Veracruz was a hotbed of violence,” Ibarrola elaborates. “It was more about self-confinement. With the pandemic you’ve had self-confinement, but we’ve been going through that for many years.”

Alejandra Aragó’s Premonitory Self-Portrait (Detail), 2017-2018.

She adds that the ghost-town-like images of the once thriving, touristed port city don’t just capture the absence of civilian life, but the absence of the state—and its ability to control crime.

Elsewhere, Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl artist Sonia Madrigal, like Alvarado, shows how language can symbolize the societal problems behind violence against women. At first glance, her video seems like a straightforward cataloguing of graffiti making romantic declarations—a familiar sight covering the walls of her community on the outskirts of Mexico City. But the spray-painted expressions of “Te Amo”, “Tu + Yo”, and “Te Extrano” have a more insidious side: the tagging can be read as males “marking” or owning their property. They also hint at the ways teenage girls are programmed for a certain kind of romantic yet destructive relationship.

Madrigal has also created a series of photographs that blur the line between journalistic photography and visual art. She captures imagery of families rallying against femicide in artistic ways, focusing on the pink crosses that have become a symbol of the protest. Interspersed are images of a ghostly, life-sized female silhouette, made out of a mirror, that Madrigal places in desolate corners of the city—-a railway track at sunset, or a remote gravel pit.

“This was a very active exercise in claiming the place,” Ibarrola explains, “not just for the women who are gone, but for the women still there who have been taken away from the streets because of fear or danger. She tells me she’s become more and more aware of the idea of making yourself more invisible; with every male looking at you, you don’t want to be seen.”

A shot from Mericeu Erthal’s Letters to Gemma series, 2017 – 2020.

The works take on a more personal point of view when you turn to self-portraits by Mariceu Erthal, whose “Letters to Gemma” series finds her standing in for a real woman, Gemma Mávil, who has disappeared; in one shot, she appears as a ghostly, fleeing blur in the bottom of an emptied-out swimming pool that’s mouldy with decay.

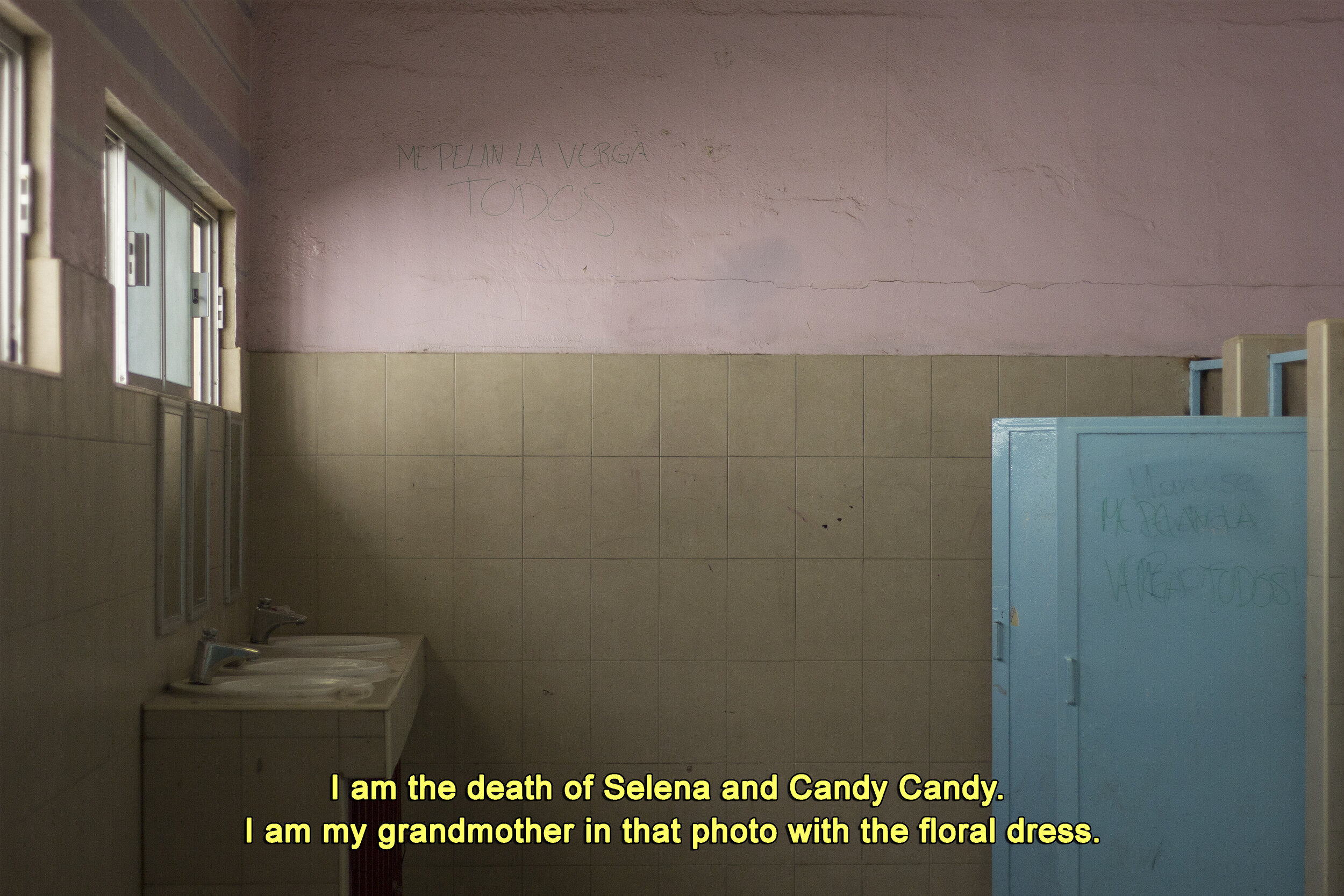

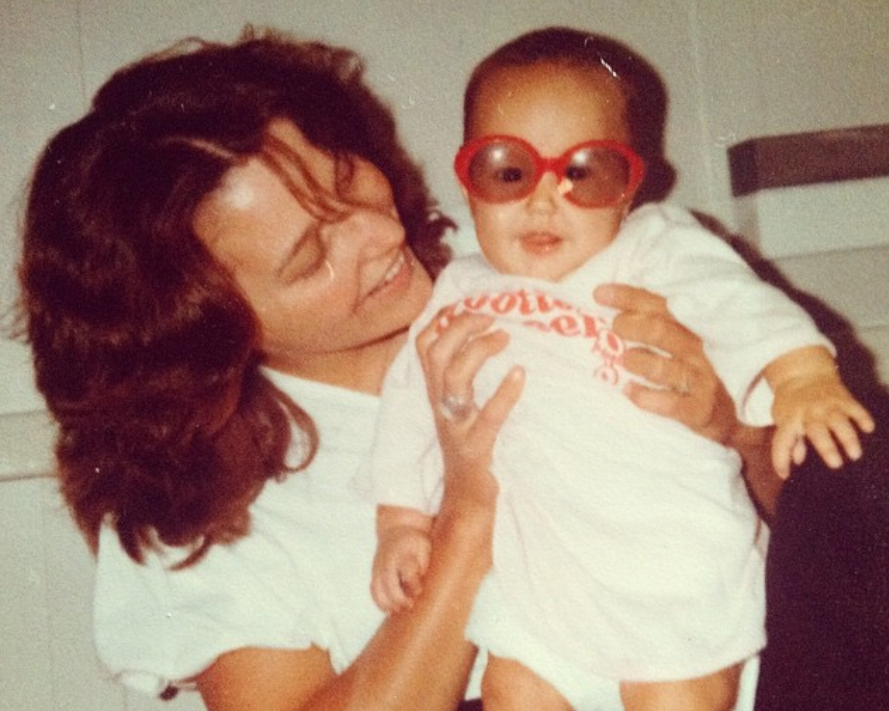

Equally personal are the photographs of Alejandra Aragón, who grew up in Ciudad Juarez. Premonitory Self-Portrait depicts empty spaces where she spent her adolescence, each shot emblazoned with text reflecting on those years. Her memories are from an era when female factory workers (“maquiladoras”) were being found murdered on the desert outskirts of the border city in alarming numbers. In some of the text, Aragón, who worked in a maquila when she was a teen, seems to acknowledge she could have easily been a victim. She touches on the female icons she was fed in her upbringing—some shots feature now-dilapidated murals of Disney princesses—and on her own experiences of danger: “The moment when that man spit on my face when I refused to get into his car”. Like Alvarado’s abandoned cafes on dusty roads, the landscape here—often empty, crumbling, or marked by graffiti—takes the place of the body, Ibarrola suggests.

Like so much more in the exhibit, there’s more than meets the eye amid the run-down sites depicted here. It’s work that draws you in to tell a story much deeper and unexpected than might be obvious at first glance.

“The landscape in a state of neglect is very much the state of women’s bodies: very damaged and hurt,” Ibarrola says.