Film reviews: Vancouver Latin American Film Festival ranges from subtle meditation to absurd comedy

With sharp visions of life in Mexico, Venezuela, and early-’70s Quebec, the event continues to reveal a deeply interconnected world where history is ever-present

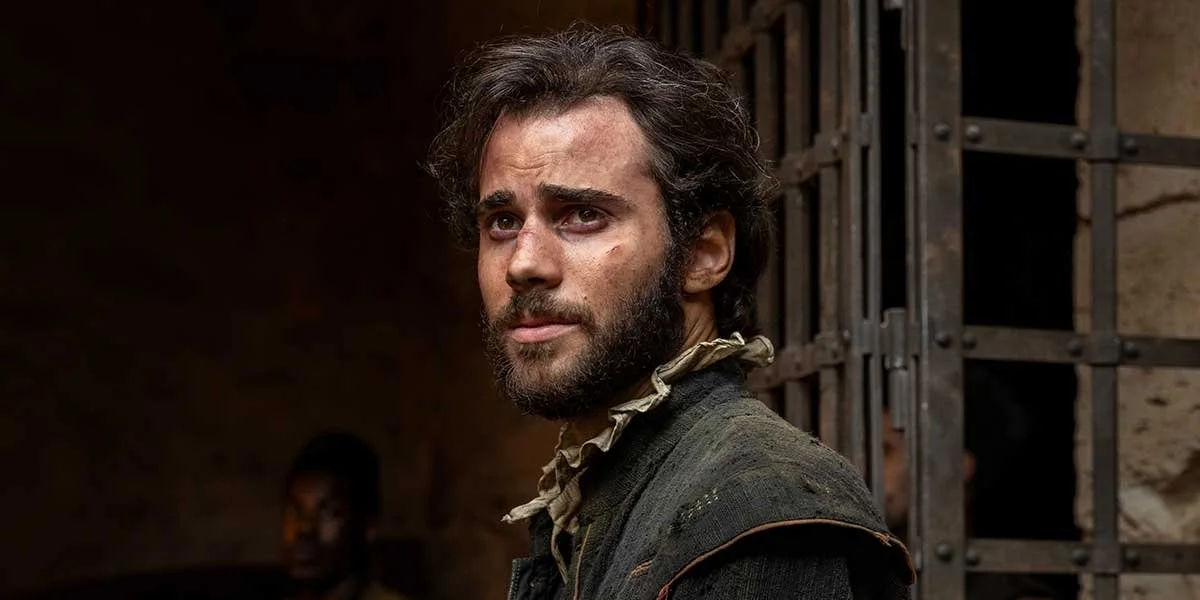

A History of Love and War.

The Vancouver Latin American Film Festival runs from September 4 to 14 at various venues

THE 23RD EDITION OF the annual Vancouver Latin American Film Festival gets under way on September 4. With more than 70 films on the program, representing 15 countries, it’s one of the largest Latin American fests of its kind on this continent. Here's a quick look at just a few standouts among the offerings.

A History of Love and War

September 11, 8:15 pm at The Cinematheque

The bloody history of Mexican land use gets the absurdist epic it deserves, with lashings of gore and comedy so broad that it spills off the screen and into your lap. The most special of the film’s exaggerated effects is Andrew Leland Rogers, who stars, minus any reasonable inhibitions, as the venal developer Pepe Sánchez Campo, first seen pitching a garish, pyramid-shaped mall to investors. By the end of Santiago Mohar’s feature, the porcine redhead Campo is a naked and mutilated Candide whose journey includes a trip to the afterlife, where he bribes a dog named Nacho. So—pretty gonzo stuff, but appropriate for Mexican politics. Glaring anachronisms refer to Maximilian Habsburg’s short 19th-century reign as emperor. Guerrilla peasant armies and cowardly academics LARPing as revolutionaries remind us of more recent activities, and there’s an interesting wink to the role played in all this by the Narcos. (Ever notice how “drug wars” always seem to explode in areas ripe for development or resource extraction?) Oh, it’s also a love story. Load up on the edibles.

Lost Chapters.

Lost Chapters

September 5, 6:15 pm at The Cinematheque

Young Ena returns to Caracas from a spell abroad to help care for her grandmother, who’s losing her memory to dementia. Meanwhile, Ena joins her antiquarian father on a quest to find a book that may or may not exist, purportedly the first novel ever to address the discovery of oil in Venezuela. Like the rest of Lorena Alvarado’s feature debut, this is a glancing but very potent idea inside a formal construct, shot as cleanly and politely as the lifestyle it observes. We frequently find ourselves looking at old postcards and other fading print images, and both Ena and her grandmother are haunted by a poem about the puniness of human experience and history. Lost Chapters arrives in the always intriguing New Directors program, and can easily be read as a romantic work about the impermanence of things. But given that it situates itself inside the besieged and unhappy middle class during Venezuela’s current political discomforts—thanks again, oil!—it’s hard to ignore a passing mention of writer Roberto Bolaño or the way that one perfectly composed frame draws our eye, ever so briefly, to a book about globalization.

The Eighth Floor

September 13, 4 pm

In 1963, as one of the founding members of the Front de libération du Québec, Jacques Lanctôt chucked a Molotov cocktail at an army barracks and went to jail for the first time. He was only 17. Less than a decade later, after the FLQ agreed to release British diplomat James Cross, Lanctôt was allowed passage to Cuba, where he lived in exile for four years (partly on the eighth floor the opulent Hotel Nacional de Cuba). This bright and touching film by Pedro Ruiz travels back to Havana with the septuagenarian, joined by Québécois actor Martin Dubreuil, who plays the younger man. (Dubreuil was born two years after the October Crisis.) It’s loosely based on Lanctôt’s 2010 memoir The Beaches of Exile, and naturally the author recalls Havana as a bustling interzone for revolutionaries from across Latin America. He even tries to find his way to North Korea at one point, although the sensuousness of Havana eventually infects this father of two with more animalistic desires. There’s much to feast on here for anyone who remembers the Old Canada, and Lanctôt still dreams of Quebec sovereignty—an idea that seems charmingly antique under our current social and political balkanization. Remarkably, Lanctôt reveals that Cuban intelligence had foreknowledge of Chile’s military coup in 1973, warning him not to go. In this light, and with Lanctôt’s admission that, following the shooting death of his comrade, 20-year-old Pierre-Louis Bourret, “the police continued the FLQ and called it a crisis,” we’re reminded that the State is always playing a game without cluing us to its rules. ![]()