Art collides with state bureaucracy in Chronicles of the Absurd, at Vancouver Latin American Film Festival

In documenting years of official disapproval and meddling, independent Cuban filmmakers Miguel Coyula and Lynn Cruz set out to trouble viewers of all political stripes

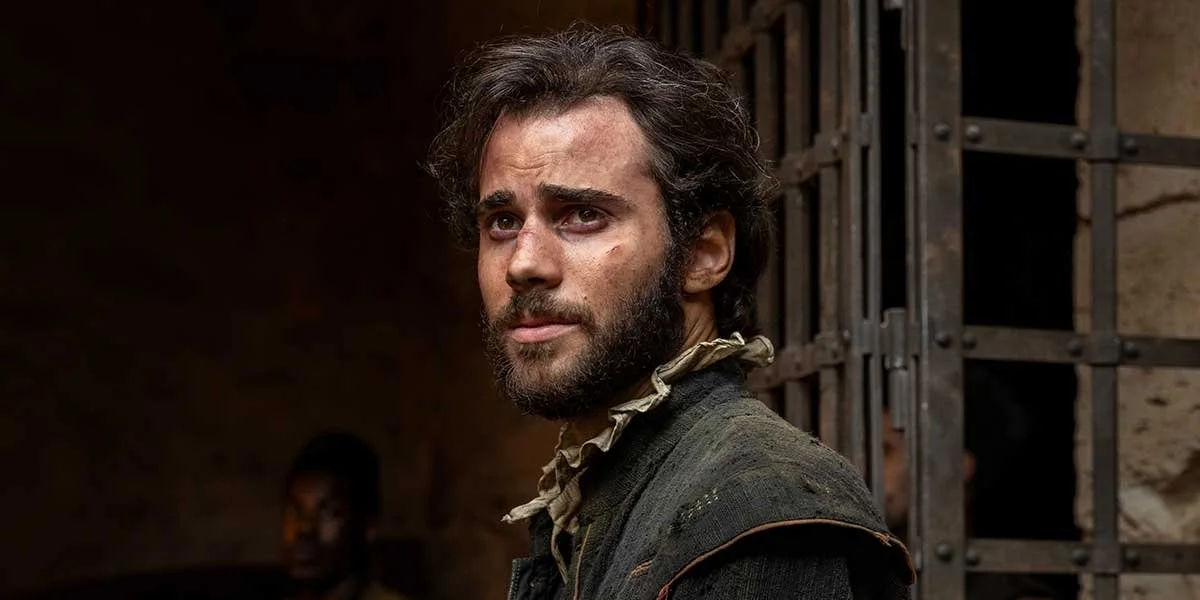

Still from Chronicles of the Absurd.

The Vancouver Latin American Film Festival presents Chronicles of the Absurd at The Cinematheque on September 13 at 6:15 pm

HOW DO YOU CATEGORIZE something like Chronicles of the Absurd? The film is constructed from clandestine phone recordings captured over 10 years while Miguel Coyula and his partner, actor Lynn Cruz, struggled in Havana to make their independent feature Blue Heart.

Says Coyula, half-seriously: “It had enough strangeness going on for me to qualify it as science fiction.”

Their activities during this time earned the disapproval of Cuban officials but also colleagues inside the artistic community. Coyula illustrates these confrontations with zero-budget handmade animations and blocks of text that buzz with the fraught immediacy of its subject.

As such, we’re not surprised to hear the blunt and brutal bullying tactics applied by the National Revolutionary Police to US-based photographer Javier Caso (brother to Ana de Armas), who’s detained for consorting with the dissident duo.

But Cruz’s wild encounter with her acting agency (Cuba only has one) exposes the more insidious bureaucratic insanity that proceeds with Looking Glass logic from compliance to the state, while her clash with the public health system reveals a yet more sinister use of red tape.

Even outside of Cuba, Coyula and Cruz are treated with suspicion and exiled to a kind of political limbo. They’re getting used to it.

“The film has been banned in Cuba,” Coyula tells Stir, “but most of my films except for one have not played at the Miami Film Festival either, because many times I’m accused of being a Communist there.” If a baffled shrug could make a sound, I just heard it.

Coyula and Cruz have stated elsewhere that “we wished we didn’t have to do Chronicles but the film just fell upon us,” and he writes about his ambivalence around activism in an illuminating essay for Jump Cut.

With Stir he can be a little more broad, arguing that the pursuit of any cause invites its own forms of suppression. In his 2017 documentary Nobody, Coyula produced a portrait of poet Rafael Alcides, whose complex critique of post-revolutionary Cuba also inflamed all sides.

“I’m always about bringing the contradictions out, and that gets me in trouble in the political arena,” he says. “I had a teacher at film school who said, ‘When you’re dealing with political cinema, make sure you upset all the members involved in the conflict, otherwise you’re doing propaganda for one of them.’ For me, the films that really marked me in my youth are the ones that made me uncomfortable, and those are the ones I try to do.”

Coyula is about to hit Miami again after a visit to New York, where Stir reaches the filmmaker after two screenings: one for his debut feature Red Cockroaches (2003) and another for Chronicles.

They were met by very different crowds. The first film, shot in New York, where he once resided thanks to a scholarship with the Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute, brought “mostly hipsters and people from Williamsburg. There wasn’t a single Cuban in the audience.”

Meanwhile, in a screening organized by the Cuban Cultural Center in New York, Chronicles won the kind of reaction Coyula will likely witness when he brings the film to the Vancouver Latin American Film Festival on September 13.

“It was great. It’s a very disturbing film, but at the same time it has a lot of humour. People were laughing, but sometimes what you hear is a nervous laugh because people don’t know how to react to what’s happening.”

Coyula’s journey is unique and reflects his own fitful place in Cuba’s cultural landscape. When he elected to return home after 10 years in New York, people thought the man was “crazy”.

“It was not because of patriotism or nationalism,” he says. “It was while being in New York that I started to look at Cuba from the distance and really found it as a great landscape for creating science fiction because of all the dystopia we live in on the island. It was very fertile ground.”

This choice also brought more than just material limitation and the inevitable official meddling.

“There are many films critical of the Cuban government made by filmmakers who never dared to do so while they were living in the island,” Coyula notes. “The sense of risk both in form and content is always beneficial for a film. I feel that for me obstacles are also a necessity in coming up with creative solutions that otherwise would never cross your mind.”

Hence we have the urgent aesthetic improvisations of Chronicles, made by a young man whose education in film was due—here’s another contradiction—to the exquisite programming of the state-run Cinematheque during Cuba’s Special Period.

In a theatre only five blocks from his house, adolescent Coyula encountered anime, Antonioni, Godard, Welles, Bertolucci, Cronenberg, Lynch…

“The first serious movie I went to see in the theatre was Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky,” he recalls. “I was 17. And it really left a big impression on me because I realized that science fiction could be more than laser guns and spaceships and Star Wars.”

Turns out that sci-fi can also be a documentary about the insanities of authoritarian state capitalism dressed up as communism. In reality, Chronicles of the Absurd is sui generis, or perhaps it’s a blending of everything Coyula loves.

“I like to mix genres,” he confesses. “I like science fiction, I like horror, existential dramas, you name it. Maybe not romantic comedies.” ![]()