Film review: Vingt Dieux (Holy Cow) mixes coming-of-age story with the fine art of French cheesemaking

Visions Ouest screens earthy charmer set in Jura agricultural region

Vingt Dieux.

Visions Ouest screens Vingt Dieux at Alliance Française Vancouver on August 27, with English subtitles

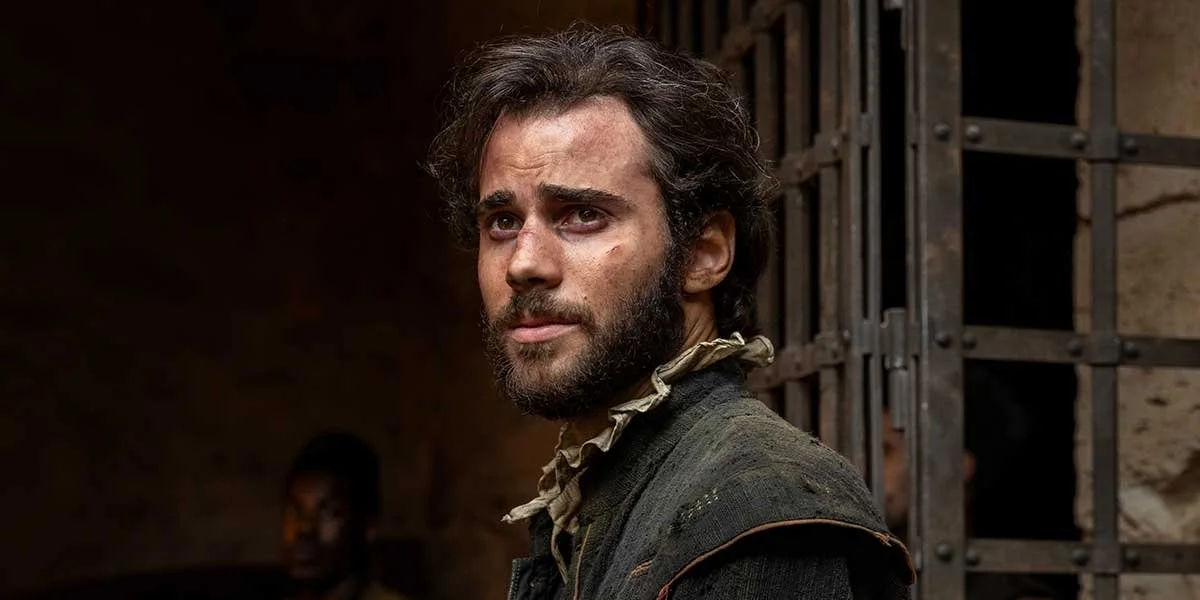

WITH A CONSTANT FACIAL expression that hits somewhere between a sneer, a smirk, and a sulk, Totone (Clément Faveau) is not the typical, endearing male movie lead. And that’s only part of the appeal of the Cannes Youth Prize winner Vingt Dieux (Holy Cow, in English).

Nothing is going right for the 18-year-old: he gets drunk at the local fairs and barn dances, can’t be bothered to help his father with chores, and loses his girlfriend because he’s too hammered to get it on. He’s going nowhere in the Jura region, west of the French Alps, where the dairy industry demands hard work and getting up well before dawn.

But a family tragedy leaves Totone in charge of a household and his little sister—and he’s going to have to get his act together. In this offbeat charmer by director Louise Courvoisier, that means selling his dad’s tractor and learning the time-worn art of fromage—the region’s beloved comté, to be specific—adding up to an unlikely but utterly engrossing mix of coming-of-age tale and fine cheesemaking. Does film get any more French than that?

Courvoisier builds a bucolic sense of place, whether through beautiful, lingering shots of misty fields and Holstein grazing, or by simply capturing the rhythms of rural life. Sometimes that means driving a truck at 4:30 in the morning to collect milk; sometimes it means scalding your hands on a vat of hot cream; and sometimes it means lending a hand to birth a breeched calf. It’s the kind of portrait that only someone who has lived and breathed that country air could capture—and apparently Courvoisier spends her hours farming when she’s not filmmaking.

In fact, her Totone, Faveau, is a real-life farmer too—and not once does this nonactor feel inauthentic. In his inscrutable expression, so off-putting to the adults and teen bullies he encounters, he conveys complex layers of insecurity, melancholy, and vulnerability. Maïwène Barthélémy, the blunt, hard-working dairy farmer that Totone learns to love and make love to, is equally unaffected. “You look like shit,” she tells him early on.

In other hands, the story of Totone trying "to adult" might come off too sentimentally. Here, Courvoisier’s wry humour keeps everything wonderfully earthbound and unsyrupy. Rough-and-tumble Totone can’t help but mess up, again and again, and it will all feel achingly, relatably familiar even if you've never set foot in a French dairy. ![]()

Janet Smith is founding partner and editorial director of Stir. She is an award-winning arts journalist who has spent more than two decades immersed in Vancouver’s dance, screen, design, theatre, music, opera, and gallery scenes. She sits on the Vancouver Film Critics’ Circle.

Related Articles

Retrospective closes with the Japanese director’s melancholic final picture, Scattered Clouds

Visions Ouest screens raucous tale of women ousted from their Quebec rink and ready for revenge, at Alliance Française

Event hosted by Michael van den Bos features Hollywood film projections and live music by the Laura Crema Sextet

Zacharias Kunuk’s latest epic tells a meditative, mystical story of two young lovers separated by fate

Ralph Fiennes plays a choir director in 1916, tasked with performing Edward Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius

A historical adventure about Cervantes and documentaries about a flamenco guitarist and a matador are among the must-sees at the expanded event at the VIFF Centre

Screening at Alliance Française and co-presented by Visions Ouest, the documentary of the folk-rockers’ rip-roaring 2023 show was shot less than a year before lead singer’s death

At the Cinematheque, Bi Gan creates five chapters, told in vastly different visual styles—from silent-film Expressionism to shadowy noir to neon-lit contemporary

Four relatives converge on an old house, discovering the story of an ancestor who journeyed to the City of Light during the Impressionist era

The Leading Ladies bring to life Duke Ellington’s swingy twist on Tchaikovsky score at December 14 screening

Legendary director’s groundbreaking movies and TV work create a visual language that reflects on some of film history’s most sinister figures—and mushroom clouds

Chandler Levack’s love letter to Montreal and her early 20s offers a new kind of female heroine; Kurtis David Harder unveils a super-energetic sequel; and Wədzįh Nəne’ (Caribou Country) takes viewers to B.C.’s snow-dusted northern reaches

Vancouver visionary behind innovative thrillers like Longlegs and The Monkey is also helping to revive the Park Theatre as a hub for a new generation of cinemagoers

Criss-crossing the map from the Lithuanian countryside to a painful Maltese dinner party, this year’s program provokes both chills and laughs

Titles include Denmark’s The Land of Short Sentences, Ukraine solidarity screening Porcelain War, and more

From Everest Dark’s story of a sherpa’s heroic journey to an all-female project to tackle Spain’s La Rubia, docs dive into adventure

Out of 106 features, more than 60 percent are Canadian; plus, Jay Kelly, a new Knives Out, and more

Event screens The Nest, the writer’s form-pushing NFB documentary re-animating her childhood home’s past, co-directed with Chase Joynt

Featuring more than 70 percent Canadian films, 25th annual fest will close December 7 with The Choral

Filmmakers including Chris Ferguson back plan to save Cambie Street’s Art Deco cinema that Cineplex had shut down Sunday

One of the weirdest Hollywood films ever made helped bring local bandleader Scott McLeod back to shadowy instrumental soundscapes

Visions Ouest and Alliance Française present moving documentary on singer-songwriter behind Kashtin

Lon Chaney’s scary makeup, a vintage pipe organ, and a score by Andrew Downing bring eerie atmosphere to the Orpheum show

Films on offer include Yurii Illienko’s The Eve of Ivan Kupalo and Borys Ivchenko’s The Lost Letter

Her National Geographic Live event From Roots to Canopy lands in the Lower Mainland care of Vancouver Civic Theatres

Director Tod Browning’s 1927 film starring Lon Chaney is characterized by sadomasochistic obsession, deception, murder, and disfigurement

The Cinematheque program proves that digital filmmaking has a future beyond artificial intelligence

Attending VIFF, NFB chair Suzanne Guèvremont has a new strategic plan that strives to reach out to the next generation

Tree canopy ecologist Nalini Nadkarni leads audiences up into the clouds to see the fascinating world of Costa Rican branches with From Roots to Canopy

Quick takes on Dracula, Idiotka, Akashi, and Ma—Cry of Silence, plus documentaries about one family’s scattered heritage and the true cost of global capitalism