Stir Q&A: Lai Hung-Chung’s Birdy explores freedom through feathers

Presented by DanceHouse, Taiwan’s Hung Dance draws on the headpieces of Chinese opera to conjure calligraphy, weapons, and birds in flight

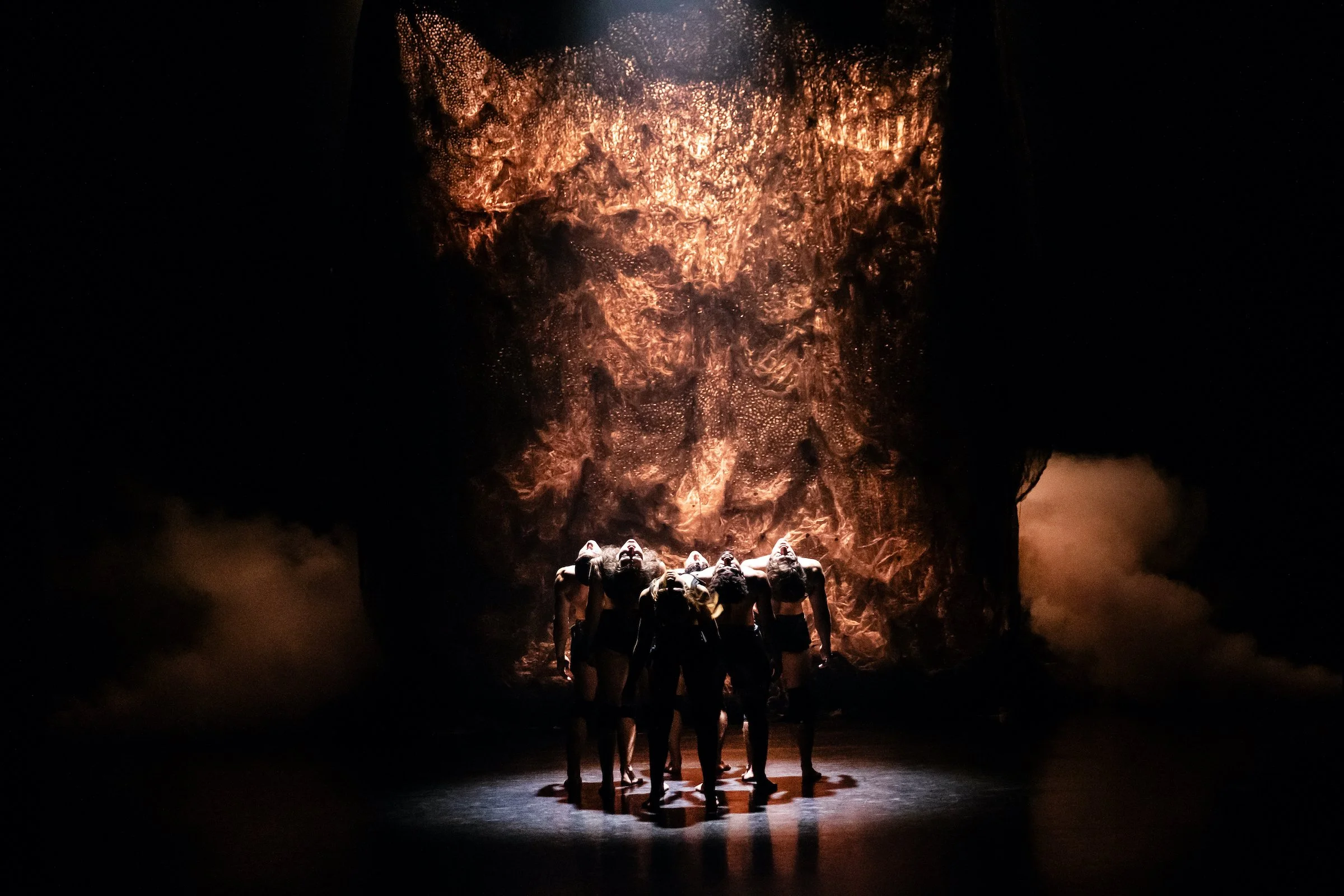

Hung Dance’s Birdy. Photo by K2 Tsai

Lai Hung-Chung

DanceHouse presents Hung Dance’s Birdy at the Vancouver Playhouse on November 28 and 29

THE LING ZI is a headpiece with four-foot-long pheasant tail feathers that was used for centuries in Chinese opera, bouncing and floating expressively as the performers moved.

Rising Taiwanese choreographer Lai Hung-Chung now reclaims and recasts the dramatic feathers in Birdy, a performance by his globe-touring company Hung Dance being presented soon by DanceHouse.

Set to a mix of percussive electronica and Chinese classical music, the eight-dancer work draws on the past but looks forward, mixing the movement of martial arts and ancient “Peking opera” with contemporary dance. Lai’s own experience crosses forms freely, with roots in hip-hop and training that spans folk and ballet.

Birdy explores freedom and flight—themes that resonate amid the politics of today’s Taiwan, as well as the wider world. In Lai’s hands, the bobbing feathers sometimes create calligraphy in the air, or conjure sharp weapons; at other moments, they evoke the murmurations of birds.

Stir caught up to the artist during his Canadian tour to talk about the individual longing for freedom, Alan Parker’s film Birdy, and Taiwan’s dance scene.

Dance is said to be thriving in Taiwan. How did you discover the art form and what is it like to be working in Taipei as a rising artist in contemporary dance right now?

I started dancing at 15, beginning with hip-hop. My teacher later encouraged me to try contemporary dance, and the transition felt very natural. In high school I began choreographing for competitions, and when I was 19, I even created my first public work for another company by recommending myself through email. Those early experiences made me realize that choreography—not performance—was my path.

After graduating from Taipei National University of the Arts in 2012, I stopped performing entirely to focus on creation. I founded Hung Dance in 2017, first in my hometown, Kaohsiung, and later in Taipei, where more dancers and collaborators are based. Some of our current dancers were actually my students from those early teaching years.

Taiwan is often described as having a “booming” dance scene, and in a way that’s true—we have strong training systems and many passionate young artists. But the local market remains small, and only Cloud Gate [Dance Theatre of Taiwan] has a large full-time ensemble. Still, Taiwan’s social and political environment gives many artists a strong desire to share our stories with the world. That desire creates the sense of vitality and momentum that people notice internationally.

How did the four-foot pheasant feather headpiece, from Chinese opera, work as a starting point for Birdy—and what did you like about the way it moved and what it could symbolize?

The opera headpieces, called Ling Zi, were one of the starting points of the work. I wasn’t interested in using them in a traditional way. I was fascinated by how the feathers extend movement far beyond the body—they react to every impulse, no matter how small. In the piece, the Ling Zi became like an external spine, an extension of power and sensitivity.

Another important inspiration came from Alan Parker’s 1984 film Birdy. The story of two young men returning from the Vietnam War, carrying trauma yet still longing for freedom, touched me deeply. There is a scene where the protagonist sits naked beside a bed frame—fragile, wounded, but still imagining flight. That duality stayed with me.

In Birdy, the Ling Zi carry both ideas: they reveal vulnerability and strength, limitation and the desire to rise beyond it. The feathers don’t write specific words—they write change, showing how every action leaves a trace in the air.

What’s your relationship to the Chinese traditions you reference in Birdy—do you see yourself as honouring them or breaking free from them, or perhaps both?

Traditions such as opera movement or Tai Chi Daoyin are not styles I try to present directly onstage—they are a training language. Tai Chi Daoyin, in particular, became significant in Taiwan after Master Hsiung Wei introduced and developed the system here. It teaches dancers how energy travels through the body, and it has become one of the core foundations of Hung Dance’s movement language.

These practices give me and my dancers a shared vocabulary. What I want the audience to see is not “This is Tai Chi” or “This is opera,” but “These are dancers from Hung Dance.” The techniques form the base, but the artistic intention goes beyond cultural labels.

So my relationship to tradition is both respectful and transformative. I use these systems as tools to understand the body more deeply, while the emotions and themes in my work speak to something more universal.

Did you find yourself literally drawing on bird movement—and do you have a fascination with birds?

I didn’t try to imitate birds literally. What interested me was the sensation of expansion—of energy moving beyond the physical body. The Ling Zi naturally create this feeling, like wings or vibrations cutting through air.

I’m fascinated by how birds can be both delicate and powerful. That dual quality became central to the movement vocabulary in Birdy. And emotionally, birds symbolize the deep human desire for freedom. In the Birdy film, the protagonist imagines becoming a bird as a way of escaping inner pain. That idea resonated with me—the longing to break away from something invisible.

To what extent does the piece express individualism and freedom for you?

For me, Birdy is less about individualism and more about the longing for freedom. It’s not a declaration of freedom, but a search for it—sometimes quietly, sometimes desperately. This connects back to the film: the protagonist’s desire to fly comes from trauma rather than confidence, and that fragility moved me deeply. In the piece, freedom is shown as something uncertain and constantly shifting. The dancers reach outward, collapse inward, repeat impulses, and test their limits. Their movement reflects a human condition: we want to break free, but we don’t always know what we’re freeing ourselves from, or what we hope to become. ![]()

Hung Dance’s Birdy. Photo by K2 Tsai