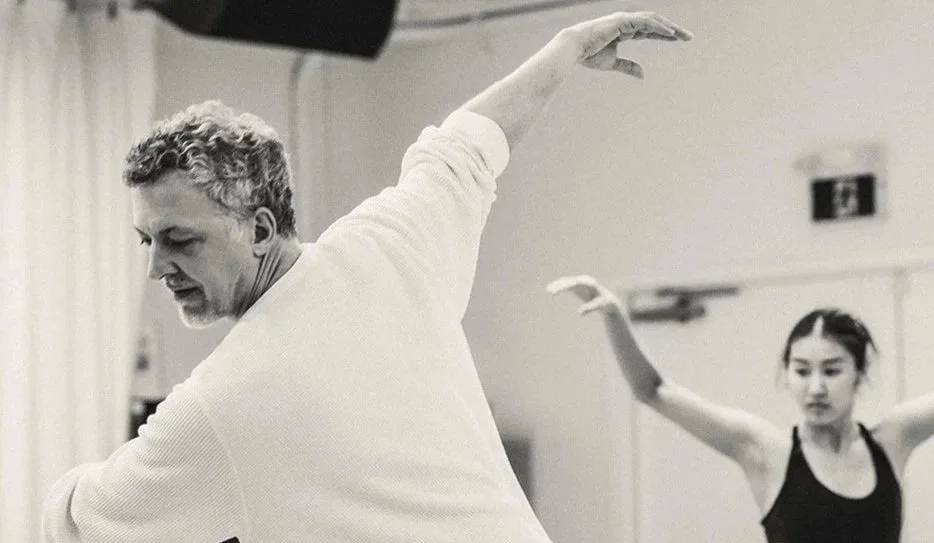

At PuSh, Alan Lake Factori(e)’s mythologically driven Orpheus paints a visceral picture of loss

In the deeply moving production, dancers embody the ancient tale of death and longing by tapping into their own experiences of tragedy

Orpheus. Photo by Gabriel Ramos

PuSh International Performing Arts Festival presents Alan Lake Factori(e)’s Orpheus at the Vancouver Playhouse on January 30 and 31, and online from January 30 to February 8

MANY PEOPLE REMEMBER the Greek myth of Orpheus not by the heroic musician’s own accomplishments, but by the tragic tale of his wife, Eurydice.

As the story goes, Eurydice was killed by a snakebite, and a grief-stricken Orpheus attempted to bring his lover back to life by travelling to the land of the dead. Once there, he performed music so heart-wrenching that Hades, king of the underworld, was compelled to grant Eurydice another chance at life under one condition: Orpheus was forbidden to look back at her. But of course, as they climbed giddily toward the land of the living and saw the first rays of sun shine down upon them, what did Orpheus do? Look back at Eurydice to share his delight with her—only to find that he had just caused her to disappear forever.

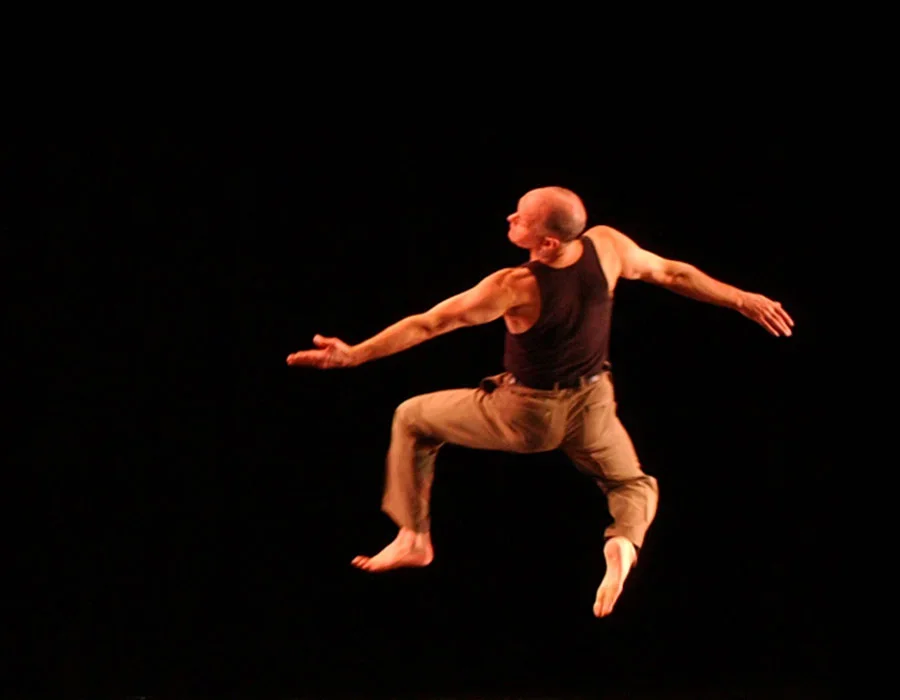

Québécois dance artist Alan Lake’s latest group production is based on the myth of Orpheus. But while choreographing it, he chose to omit many literal aspects of the Greek figure’s mythology, such as mentions of Eurydice and Hades, in favour of exploring the deeply personal tragedy at the heart of his story.

“We decided to just let go and ask the dancers how they feel,” Lake tells Stir by Zoom from Quebec City, where he runs his company, Alan Lake Factori(e). “The seven humans really collaborate with this creation: What is your small hell? What are you going to do if you lose your child? We began to talk about this, and it began to be part of their [own] tragedies, like les tragédies grecques.”

Orpheus will have its Western Canadian premiere at this year’s PuSh International Performing Arts Festival. Lake, who has a background in painting and sculpture, is no stranger to creating works that draw on mythological themes. His haunting, desperation-filled production Le Cri des méduses, which showed at PuSh in 2023, revolved around a jumble of intertwined bodies inspired by French Romantic artist Théodore Géricault’s oil painting The Raft of the Medusa.

Orpheus is the second in a four-part series of Lake’s that will centre on the titular figure. Part 1 was a theatre production called Le Mythe d’Orphée that premiered at Quebec City’s Le Théâtre du Trident in 2024, with a script by Isabelle Hubert. Next steps for the piece are a film and a site-specific performance (likely in nature or an ancient building).

Alan Lake. Photo by Michael Pinault

The movement in the dance production alternates between soft and intimate, and raw and visceral, as the performers investigate how to embody the feeling of loss.

“I think that when you lose someone, there’s a step where you want to probably go too,” Lake reflects. “You want to die too, because it’s too much. If I lost my daughter or my parents, you know, it’s like, my god, I don’t want to live anymore. I just want to go. But then, after, there’s a contrast of situations where I think that you want to live for both. You want to breathe again…because life is too great, even if everything is collapsing around [you].”

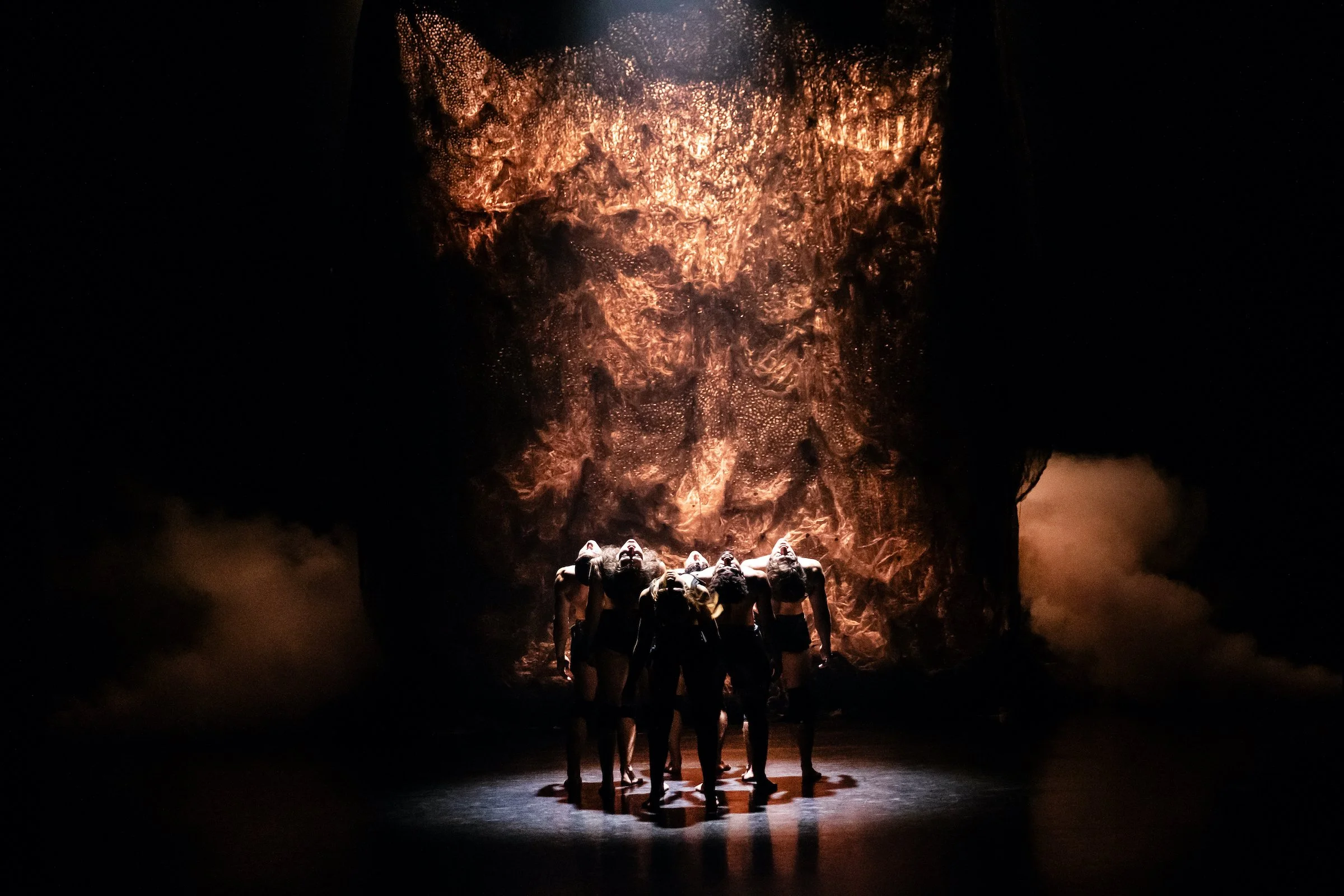

Most strikingly, there’s a massive curtain that the performers manipulate throughout the work. Using a pulley system made of ropes and carabiners, the dancers change the height and orientation of the fabric themselves, climbing it when it stretches to the rafters—as if they’re ascending from hell—and curling into it when it’s bundled on the floor, as though they’re melting into pools of lava.

All of this will be heightened by the music of Antoine Berthiaume, who will be seated at the side of the stage during the performance, acting as an omniscient narrator. He’ll be prompting the dancers’ movements by weaving live guitar sounds with a pre-recorded score.

Lake describes the world that the performers are caught up in as “onirique”, meaning “dreamlike”.

“Humans always touch together—and how do we touch?” he ponders. “How can I jump into you, and then you catch me? [When] you drop me, how can you help me to get up? So all these situations of hanging and jumping relate to each other. This collectivity, we’ll rise together, and always…find a way to get out too, because we want light. We begin with the tragedy, and then it’s how this collectivity is gonna find…the light at the end to get out of hell.”

Folks who purchase tickets to see Orpheus at PuSh will also get a free code to view Alan Lake Factori(e)’s dance film Parades online. Filmed without physical contact during the pandemic and brimming with symbolism, the work uses parallel editing—four shots placed side by side in one frame—to show bodies morphing, regenerating, and “colliding” with one another without ever having been in the same space.

Ultimately, a priority for Lake and his dancers is going above and beyond to ensure their productions are easy to understand—all while maintaining layers of contextual depth.

“I think that the way that the Factori(e) works, with all the symbols and the sets and the visual-cinema mix, can really connect every kind of public,” the choreographer affirms. “So it’s an invitation to exchange together.” ![]()