Dance artist Jeanette Kotowich's Kisiskâciwan journeys to a sacred valley, and into her own identity

Choreographer’s profound new solo premieres on the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation

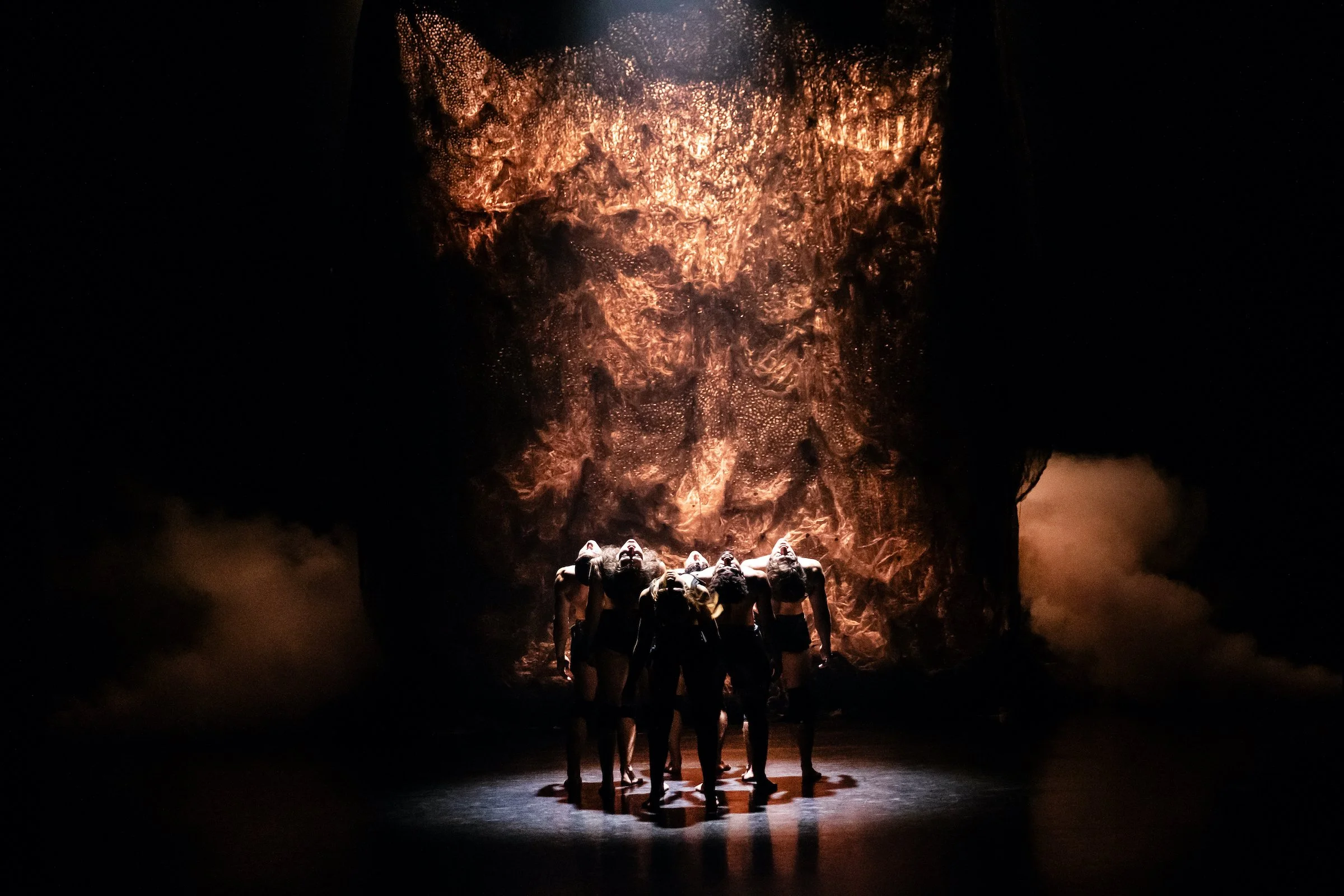

Photo by Yvonne Chew

Photo by Jeanette Kotowich

Jeanette Kotowich's Kisiskâciwan premieres at the Scotiabank Dance Centre on September 30 and October 1

SEVEN YEARS IN THE making, dance artist Jeanette Kotowich’s much-anticipated new solo Kisiskâciwan was inspired by the body’s connection to the land—and, specifically, the place in Saskatchewan where she spent summers at her family cabin.

Saskatchewan’s Kah-tep-was Valley is a place of endless sky and rolling grass—and the Nêhiyaw Métis artist has fond memories of it.

“The cabin didn't have running water, and some of the kids would sleep in a tent,” Kotowich says. “It was lakefront, and my dad had a canoe and a small sailboat. My siblings and I would put on shows and my parents would come; admission was a few rocks.”

But the Kah-tep-was doesn’t just hold nostalgic memories; it holds sacred value to Kotowich’s family, and the ancestors who came before them. “I remember that Dad would sometimes go and shoot bows and arrows, and because he punctured the Earth, he would put tobacco in the wound,” she recalls.

It is a vast landscape, and so are the themes in Kotowich’s new work—a piece that not only draws on a specific location but also alludes to its pre-human beginnings, as glaciers carved the valley. In addition, the piece reflects a profound discovery of the inner self—a space as vast as any prairie.

“It’s almost the body as the landscape, and the landscape as the body,” she explains.

For years, the artist has been a striking performer in the Indigenous-contemporary ensemble Raven Spirit Dance; more recently she’s expressed her voice through the ensemble work KWE. But this solo has been an extended dive into Kotowich’s own roots—where she comes from and what the meaning of home is for this Vancouverite of 18 years. It was supposed to have premiered in 2020, but the pandemic delay has allowed the artist to push even deeper into her ancestry and identity.

“Coming out of being so in-demand as a company artist, supporting other artists’ visions and being attached with other Indigenous nations, this piece is honouring my own voice and my history and my determination to create a process,” she tells Stir with emotion. “It feels really good. I feel really ready. I think if I’d premiered the work two years ago, like it was planned, it would have been really different.

“I feel like the work was waiting for me to mature to this place and be able to have it be the true expression.”

Creating her own method of land-based practice along the way, Kotowich returned to the Saskatchewan valley several times in her lengthy research process—at one point even living there in a trailer. She took walks, made notes, gathered grasses, and heightened her awareness of the air and sounds. “The horizon is much different than here,” she reflects. “It’s more than half sky when you're there.” Imbuing all of that with deeper meaning are the foundations of Cree cosmology—the heavens opening up to stars, and Mother Earth coming into being.

Her new dance work incorporates a large silver tarp that shape-shifts to capture the expansive ideas in Kotowich’s piece. “It has so much capacity to make shapes and can’t really be controlled,” she says.

Kathleen Nisbet creates the live soundtrack, through fiddle and vocals (also performing before the show each night at 7:30 pm).

Kotowich reveals that Kisiskâciwan will build toward a place of joy and release—and a nod to the beloved Métis jigging she grew up with.

The dance artist, more than in any other piece she’s performed, strives to make herself vulnerable in the work.

“I’m an emotional person and that does actually serve my practice, so instead of trying to suppress it… I just live in it,” she explains. “My work is a place to hold what I’m feeling.”

It’s through that deeply human vulnerability that Kotowich hopes to connect with her audiences—a fact made all the more significant by the fact that the long-awaited work premieres on Truth and Reconciliation Day. “I feel if anybody is wanting to do something that day, this is a way for them to be engaging with Indigenous content that's not super-political,” she says.

“There's an invitation for witnesses or audience members to remember their own humanity, to remember their own relationship to land, and to remember their own relationship to home,” she adds. “We’re all nomadic people. It’s also to witness somebody’s joy and vulnerability and generosity onstage through a story.

“It’s really important to me that the audience is invited into my process,” she emphasizes. “This is part of dismantling colonial constructs within theatre spaces—even if it’s sharing my vulnerability and allowing people to witness it, along with a lot of strength and joy.”