Carmen Aguirre tells a multifaceted story of art and resistance in Fire Never Dies: The Tina Modotti Project

At the Cultch, theatre artist employs episodic structure, photo projections, and an array of styles to capture the complicated photographer and activist

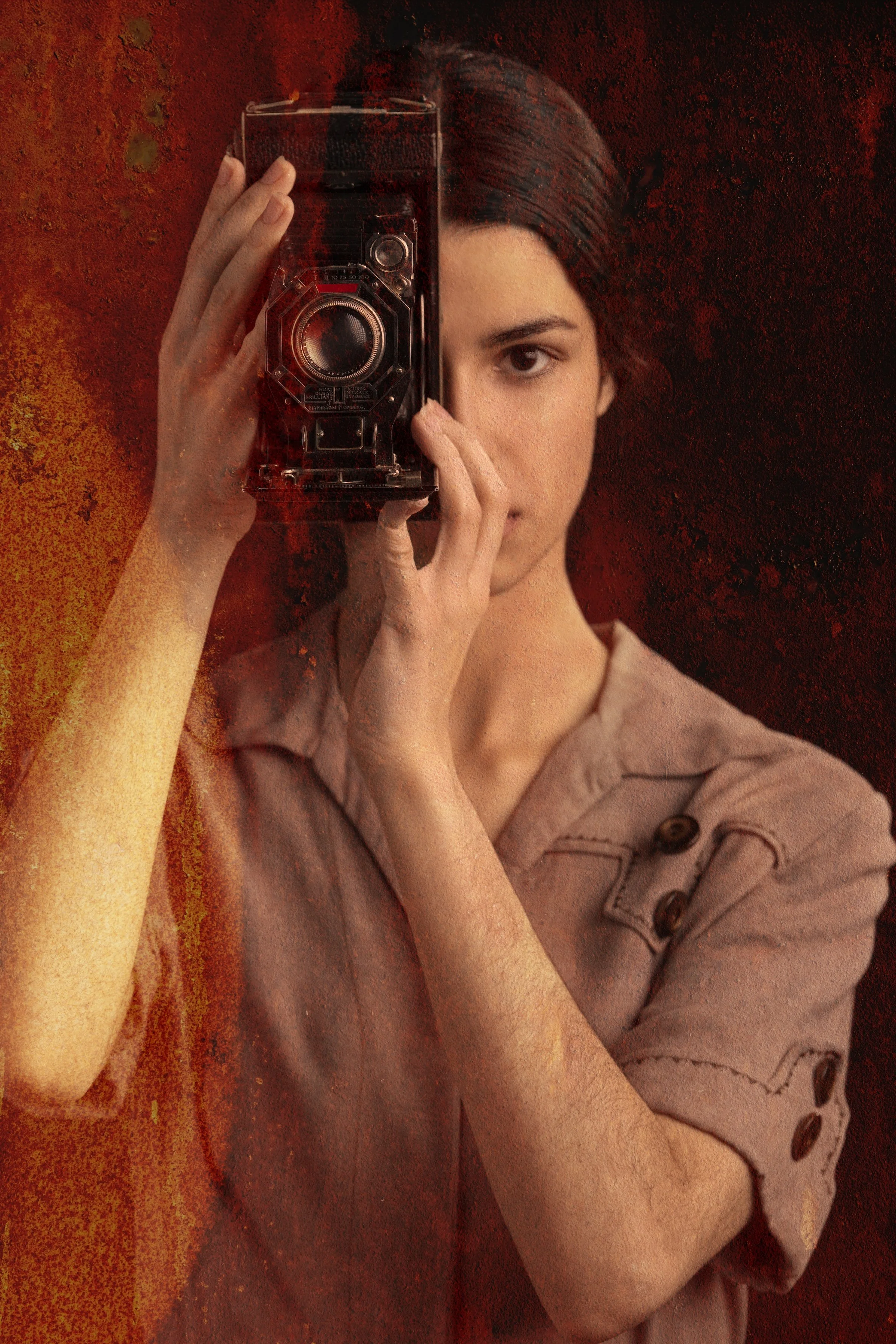

Marianna Zouzoulas in Fire Never Dies: The Tina Mondotti Story. Photo by David Cooper

The Cultch and Vancouver Latin American Cultural Centre present Fire Never Dies: The Tina Modotti Project at the Historic Theatre from October 15 to 26

TWO HANDS, DUSTY and calloused, rest momentarily in closeup atop the handle of a shovel. In the striking 1927 black-and-white image that sits in the MoMA collection, photographer Tina Modotti celebrated the quiet dignity of a Mexican labourer. Called Worker’s Hands, it also expressed Modotti’s deep commitment to communism, her political activism a defining aspect of her life and art.

Her powerful photographs become another character in the new show Fire Never Dies: The Tina Modotti Project, a multimedia play from Vancouver-based author and theatre artist Carmen Aguirre. It seems a perfect fit: the Santiago-born artist, whose autobiographical book Something Fierce recounted her work with the resistance movement against Chile’s military dictatorship in the 1980s, has long been drawn to themes of exile, revolution, and social justice. For Aguirre—just as it was for Modotti—political activism is always tied into her artmaking.

Aguirre first discovered Modotti 35 years ago, reading a fictionalized account of the artist’s life—Elena Poniatowska’s Tinisima—while studying acting at Studio 58.

It’s taken her this long to adapt the story—one that moves from an upbringing in abject poverty in Italy to crossing the Atlantic to the U.S. in 1913, at just 16, and then to becoming part of the thriving 1920s Mexico City art scene of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, even appearing in the latter’s famous murals. Along the way, Modotti made a name for herself with her arresting photographs of the working class and Mexican Indigenous culture—then gave it all up to head to Europe and beyond, helping the International Red Aid in Moscow and Spain as part of the anti-fascist resistance of the 1930s.

“I was very compelled by the story because here was an artist who was a master at her craft, of photography, who was also a revolutionary and who was trying to reconcile her artistic practice with her revolutionary commitment,” Aguirre says on a break from rehearsals for the Electric Company Theatre production. “It was also really refreshing to see her photographs, and the subjects, in terms of the people that she was photographing: the poor. And the lens is not being exploitative or appropriative, but the lens is from a person who comes from that class as well.”

Carmen Aguirre

Tackling the story of Modotti’s life was no easy matter. As Aguirre says with a laugh, her love life alone could fill a few soap operas. (To name only a few of her lovers: Kahlo, Rivera, American photographer Edward Weston, and Cuban revolutionary Julio Antonio Mella.) Modotti’s upbringing, her art, and her revolutionary work spanned decades and continents. Aguirre finally came up with a way into all that: beginning at the end of Modotti’s life, with her untimely death at just 45, in 1942, from a heart attack in the back of a Mexico City taxi cab. From there, the character reflects back on the turning points in her life. Via a multitasking seven-actor cast, with Marianna Zouzoulas in the title role, Fire Never Dies flashes back to 25 key episodes, each stylistically different—from a film-noir-tinged scene of espionage in Berlin to naturalism in Mexico’s art-party scene.

“It gave me the container to be able to look at different moments in her life without them having to necessarily be one scene feeding directly into another scene,” Aguirre explains of the structure. “It’s more of a kaleidoscope. And also it freed me up to try different styles for different scenes, depending on what the scene was asking for. From that anchor, we can go anywhere stylistically, as well as in terms of content.”

Aguirre says she’s also borrowing from Zarzuela, a form of theatre that had its birth in 17th-century Spain and found its way to Latin America, including the Chile where she grew up. Zarzuela bounces freely between spoken dialogue, sung arias, operatic elements, and traditional dance, incorporating everything from social satire to folk music.

“I remember seeing this kind of stuff when I was a kid; like, I’m talking a tiny child before the coup,” Aguirre relates, referring to General Augusto Pinochet’s takeover that sent her family fleeing Chile in 1973, when she was five. “It’s like a hodgepodge of ‘There’s singing, there’s dancing. Now there’s naturalism. Oh, now somebody’s doing a fashion show! Okay, now we’re in a completely different style, but it all makes sense.’”

Through the mix of genres and scenes, Aguirre says she’s trying to explore three questions that do not have easy answers.

“I do not have the answer for them because it’s not a message play,” Aguirre explains. “The questions that I’m pondering are: What is the purpose of art in the face of fascism? Can art serve the poor, and if so, how? And what is the personal cost of militancy?”

Ambitious theatre work is nothing new for Aguirre, whose semi-autobiographical 2020 production Anywhere But Here, also with Electric Company Theatre, employed full-blown magic realism, as well as rap sections, to tell the story of a family travelling by car back to Chile from Canada.

Aguirre is working closely with a technical team to bring together the myriad photographic projections, multigenerational cast, choreography by James Gnam, and mixed forms of theatrical storytelling. But she allows that the most challenging part of Fire Never Dies may come down to its boundary-pushing content—and the fiery woman at its centre.

“The fact that we’re uplifting a woman who was unabashedly a communist—and we’re not shying away from that,” Aguirre says. “There’s no line or scene or anything in the play that tries to paint that in a bad light. That in and of itself, to do that on a mainstream stage, in North America—which, as far as I’m concerned, is the most capitalist place on Earth—is already pretty ambitious.” ![]()

Marianna Zouzoulas in Fire Never Dies: The Tina Mondotti Story. Photo by David Cooper