Ali Sethi joyfully bends and breaks the rules of Pakistani music

The singer’s metaphor-rich work is rooted in the traditions of ghazals and Sufi poetry

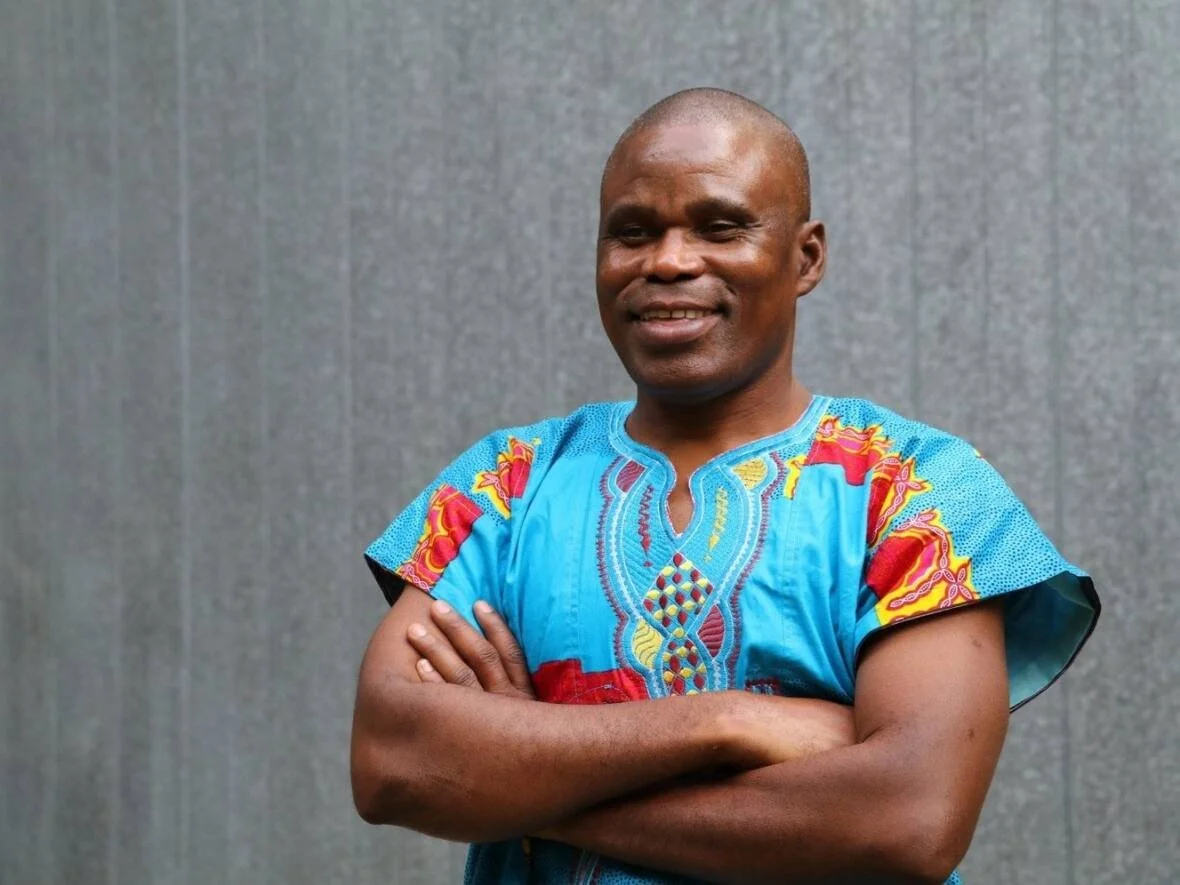

Ali Sethi

Ali Sethi is at the Chan Centre for the Performing Arts on October 19 at 7 pm

ON THE SURFACE, 2025 might not look like an opportune time for a gay, Muslim, Pakistan-born intellectual to make a bold move into popular music—and yet on another level, Ali Sethi’s arrival could not be more welcome. Yes, there is increasing bigotry in the world, not only from Christian nationalists but also from conservative forces within Islam and elsewhere. Yes, cultural diversity now flies in the face of official policy in the United States, where Sethi spends much of his time. And, yes, taking a show on the road has become increasingly fraught in this time of ever-higher walls and targeted detainment. But even at its most accessible—and he has penned some genuine club bangers, as well as thoughtful meditations on love and difference—Sethi’s music carries a message of joy and resilience that might be exactly what this historical moment craves.

The 41-year-old singer, who plays the Chan Centre for the Performing Arts on Sunday, October 19, did not have to choose music as his medium. Born to Pakistani journalists Najam Sethi and Jugnu Mohsin, Sethi studied at Harvard, graduating with a degree in South Asian studies. In 2009, he published a novel, The Wish Maker, which won comparisons to Khaled Hosseini's best-selling The Kite Runner and has so far been published in seven languages. But music, it seems, chose him.

“I grew up in Lahore, in Pakistan, where music was very much in the air, especially sacred music, devotional music,” Sethi explains in a quick but revelatory pre-tour interview. “It’s kind of a ritual for us, as a people, for weddings, for funerals, for political rallies, for the cycles of the seasons… Spring has its own melodies; rain, monsoon has its own dramatic melodies. And there were songs, folk songs, that commemorate all the amazing historical dramas that have played out on the soul of my country, which has a recorded history that goes back at least 2,000 years. So I think music became, for me, a way to kind of engage with the layers and the textures and the rich embroidery of history and of culture.

“Especially after the 9/11 period, when America was very militarily involved in Afghanistan and Pakistan, there was also a great pressure within the region for young people, especially, to make a stark choice between tradition—to be conservative and orthodox and, you know, on one side—and modernity, which was deemed to be Western and progressive and on the other side. I think music allowed me to playfully upend that binary and say to myself—and then to other people in my generation—that tradition need not be dogmatic or conservative, and that there might be ways to build bridges between heritage and the future.”

Sethi’s hopes play out in the sound of his music. His art is rooted in the ghazal, a song-form that fuses the secular and the sacred by embracing both the most sensual of all melodies and an ecstatic longing for transcendence, whether in the arms of a lover or in contemplation of the divine. But while he’s a serious student of the form, he’s molding it into new containers: his recently released solo debut, Love Language, adds programmed beats and auto-tuned choruses, while 2023’s Intiha, a collaboration with Chilean-American ambient producer Nicolas Jaar, is an especially lovely exploration of electronic textures and impassioned singing.

Sethi sees this aspect of his work as emblematic of a larger trend within popular culture: placing an authentic expression of one’s heritage within globally accessible frameworks. “Some of my favourite contemporary musicians, even on the American pop-music scene—people like Beyoncé, people like Brandi Carlisle, even people like Elton John, Dua Lipa… these are artists who are reclaiming and updating genre spaces such as country, disco, folk, Americana, and imbuing them with new interpretations. Kind of expanding the category to include a more contemporary experience of life. The Spanish artist Rosalía has done that in a very exhilarating way with flamenco, for example, which is a musical form that is rich and old. She trained in it in a kind of rigorous way, but then she ran with it. And I think that’s what I aspired to do on Love Language: to run with ragas, as it were. You take something that is ancient and that is very central to your people’s sense of where they come from, what they come from, something that feels essential or quintessential, and then you take it further.

“You know, I spent more than a decade being an apprentice to masters of the form, just learning the texts and the standards and trying to deliver them as faithfully as can be,” he continues. “And then eventually there came a point where I just started to play with those texts. It’s great fun to bend the rules and even break them, when you know them.”

It helps, Sethi points out, that traditional ghazals are often based on Sufi poetry, which even from its inception in 12th-century Persia has been a body of slippery, metaphorical, and multilayered work.

“It’s a polyvalent form in which the poet is silhouetted in this self-absenting way that ultimately becomes a very powerful form of confession—a kind of playful disclosure about the self and the possibilities of the self,” he says. “Rumi, of course, is the most famous practitioner of the ghazal, but also Hafez in the Persian tradition, and then Ghalib and Faiz in the Urdu tradition, as late as the 20th century. And the ghazal relies on metaphors to convey its meanings, and metaphors I’ve always been drawn to because metaphors are coded. The stock metaphors of the ghazal, like the half-empty wine cup or the desolate tavern or the rose that comes with thorns… It’s all this baroque imagery that on one hand feels maybe outdated or medieval or pre-modern, but I’ve always found it to be very useful, and a very powerful way of engaging with this polyphonic and sometimes cacophonous present.

“A metaphor is a broad church,” he adds. “It invites interpretation. The ‘desolate tavern’ can be a broken heart; it can also be a country with a bad government. And I think that in times of censorship and repression—which was every day when I was growing up in Pakistan, but now seems to be the case in many parts of the world, including America—metaphors help us express ourselves in profound and illuminating ways without having to limit ourselves to one interpretation. And that’s a healthy and civilized way to do discourse in an otherwise polarized culture, if that makes sense.”

It certainly does, especially when Sethi explains that the ghazal’s embrace of ambiguity is a perfect fit for those who live between cultures or between gender identities: the very people most often persecuted by “bad governments”.

“Things like mysticism, abstraction, song, poetry, transcendence: these are ways of creating a generosity of spirit that a lot of people can participate in, even when they’re coming from different ideological camps,” he contends. “That’s certainly what Sufi poetry and qawwali and other kinds of music did for people in my culture. Conservatives and radicals could sit together and listen to a ghazal recital and find something in that one song that applied very specifically to their own existence and their own subjectivity, and I feel that in America today that’s a rarity. There are fewer and fewer ways for people to come together across their different belief systems, their different tribes, their different allegiances.

“It might sound like a very irrational desire, but somehow I feel like it’s my job to create, through music and performance and humour, ways for people to come together,” he adds. “So I’m bringing songs that are now sweet, now satirical, now tender, now inflamed as a kind of shamanic ritual that I hope will exercise and exorcise what we’re feeling, in a spirit of togetherness.” ![]()