At DOXA, Manufacturing the Threat unravels a problematic chapter in the name of national security

Filmmaker Amy Miller’s dissection of the BC homemade-bomb caper raises questions around democracy

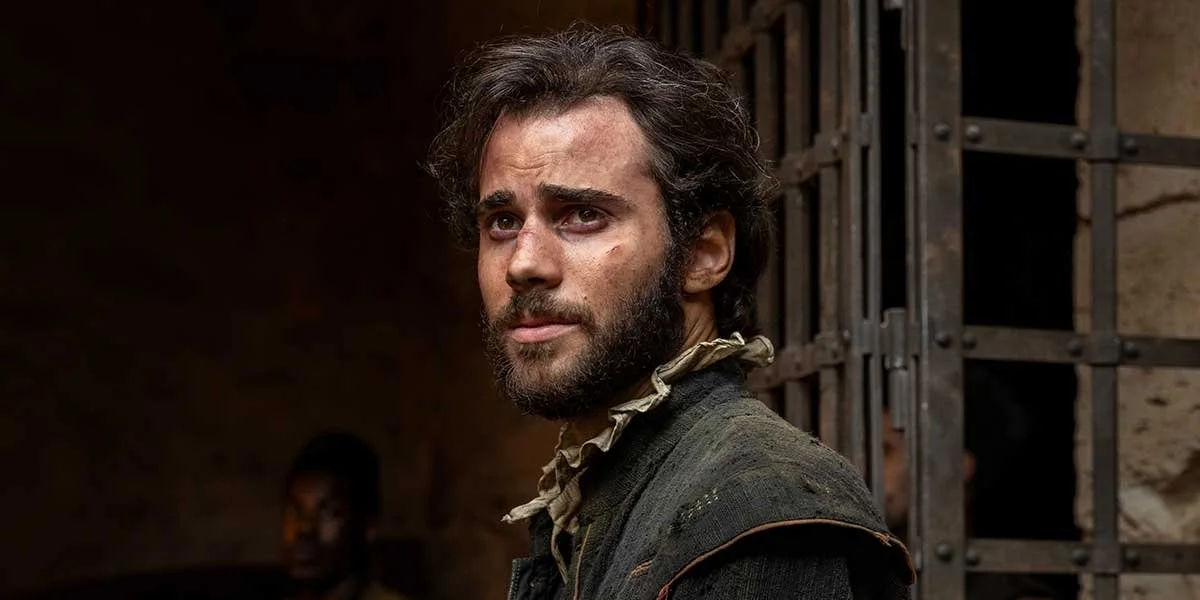

Accused in 2013 plot to plant bombs at the B.C. Legislature, John Nuttall and Amanda Korody, seen in the new documentary Manufacturing the Threat, were freed after a B.C. Supreme Court judge found police had entrapped them.

DOXA Documentary Film Festival presents Manufacturing the Threat at VIFF Centre on May 5, 7:45 pm. Filmmaker Amy Miller hosts a masterclass May 6 at SFU Woodward’s

IT WAS ONE OF THE the shabbiest episodes in Canadian law enforcement history. In 2013, John “Omar” Nuttall and his wife Amanda “Ana” Korody were apprehended after planting a number of homemade bombs on the grounds of the BC legislature. Trumpeted by the RCMP as a victory against Islamic terrorism, the perps spent three years in prison before a BC Supreme Court judge sprung them and said the quiet part out loud: Nuttall and Korody were victims of entrapment and had been manipulated by the feds in a plot that they had neither the wits nor the desire to execute themselves.

“This was an inside false-flag job perpetrated by the Canadian government,” is Nuttall’s blunt statement, interviewed in the opening minutes of Manufacturing the Threat. Supreme Court findings aside, Amy Miller’s documentary leaves no doubt about that.

Surveillance footage gives us a picture of the psychological techniques used to radicalize and box the couple inside the RCMP’s scheme, including, Clockwork Orange-style, bombarding the couple with videos of Muslims being tortured. It’s frequently heartbreaking. At times an anguished Nuttall feebly attempts to delay the terror plot without arousing the suspicion of his handlers, all of them undercover cops and spooks posing as jihadists. Fear of reprisal became their sole motivation. In Nuttall’s words in the film: “You’re putting on an act to impress them, so they think you’re hardcore. And they’re putting on an act. And you don’t know they’re putting on an act. So neither you or the cops know that you’re all acting in a Truman Show movie starring you, with the main goal of putting you behind bars for the rest of your life.”

Receiving its world premiere at the DOXA Documentary Film Festival on May 5, Manufacturing the Threat shows us how this grim and pointless caper exploited a vulnerable couple from society’s bottom rung, but the bigger question is why. Says writer-director Miller, calling from her office in Montreal: “I think the film’s argument is that there’s a lot of money to be made, there are a lot of people vested in maintaining this methodology and this notion of national security because they benefit. It’s a big industry and it’s spent the last 20 years saying the fight is terrorism. It’s hard to fight the tide.”

Prior to that, the security state was always a steadfastly expanding entity. In Manufacturing the Threat, York University’s Reg Whitaker notes that “Islamism" simply replaced the Cold War as the pre-eminent threat to Canadian national security after 9/11. Ryerson’s Pamela Palmater and author Steve Hewitt remind us that the RCMP was initially conceived to “ethnically cleanse the Canadian plains.” Author Jane Gerster, among others, recounts a long history of domestic spying and infiltration designed to poison labour and other dissident movements on the left while creating destructive mischief on the extreme right. In turn the national security apparatus justified itself with ever-increasing budgets and mounting violations of citizens rights. As Whitaker says, “Politics in a liberal democracy is policed,” which naturally eliminates any meaning from the word democracy.

Beyond all that, Miller’s film asserts, is the deepening problem of secrecy, accelerated by the creation of CSIS in 1984 and a subsequent program of legislation designed, in the words of Islamic law specialist Azeezah Kanji, to “retroactively legalize abuse by the NatSec services”. Says Miller: “Canada’s access to information is dismal. In the States, in terms of what the FBI or the CIA has done, there’s a lot more information than we have in Canada about CSIS and the RCMP. And that’s a problem! We can’t say policing powers are going too far if we don’t know what they’re doing. It’s a game where we don’t know where the goalposts are, what the rules are, what’s it’s costing, how much it’s being done, how many people it’s impacting. How much is so-called Islamist terrorism a threat when the only case I’m familiar with, the only big one—this one—was exposed as entrapment?”

Inevitably, a film like Manufacturing the Threat provokes questions about other mysterious events in our recent past. Gabriel Wortman’s 2020 shooting spree in Nova Scotia left 22 people dead. He fit the profile of an RCMP informant or protected asset even if last month’s public inquiry made every effort to look the other way. “That was actually one of the cases I was looking at, and I wanted to see if there was any way to pull it into the film,” says Miller. “But again, there’s so little information that, unfortunately, it might be that only in 10, 20, 30 years, through many people investigating from different angles, that, maybe, we might know something. And my heart goes out to the families who are wondering and have questions.”

With only cosmetic accountability for the security services, along with historic mission creep, secret agendas, and sweeping advances in surveillance and data collection, should the average Canadian be more than a tad nervous about all this? What about Miller? Her career began by taking a hammer to military and business interests with 2009’s Myths for Profit: Canada’s Role in Industries of War and Peace. Does she worry about making the proverbial list? “Nah,” she scoffs, “I mean, what would the list be? ‘Oh no, it’s a documentary filmmaker who’s trying to speak out and do popular education!’ Here’s the thing: you don’t need to do anything with filmmakers, all you need to do is ignore them. That’s all that needs to happen.”

At the risk of bringing unwanted attention, don’t ignore Amy Miller.