Film review: Resurrection's dream scenarios pay dazzling tribute to a century of motion pictures

At the Cinematheque, Bi Gan creates five chapters, told in vastly different visual styles—from silent-film Expressionism to shadowy noir to neon-lit contemporary

Resurrection

The Cinematheque presents Bi Gan’s Resurrection from January 7 to February 1

BI GAN’S EPIC new Resurrection has more moments of breathtaking visual wonder than words of actual dialogue.

The Chinese filmmaker’s opus needs to be seen on the big screen, a fact that makes the upcoming showings at The Cinematheque this month a bit of an event.

In one scene, a giant arm reaches in to adjust a light fixture on the set of an old Chinese opium den. Bloodied hands play a vintage theremin. Guns shatter glass in a hall of antique mirrors. A body falls through the air into a snowy mountain temple. A wax movie house melts into oblivion. And, in a final, unbroken 40-minute tracking shot, we race through cramped alleyways, crooked stairways, rowdy brothels, and packed karaoke bars—all bathed in red neon light.

What is it all about? Let’s just say it’s better to lose yourself in the sensorial experience of Resurrection than to try to understand it.

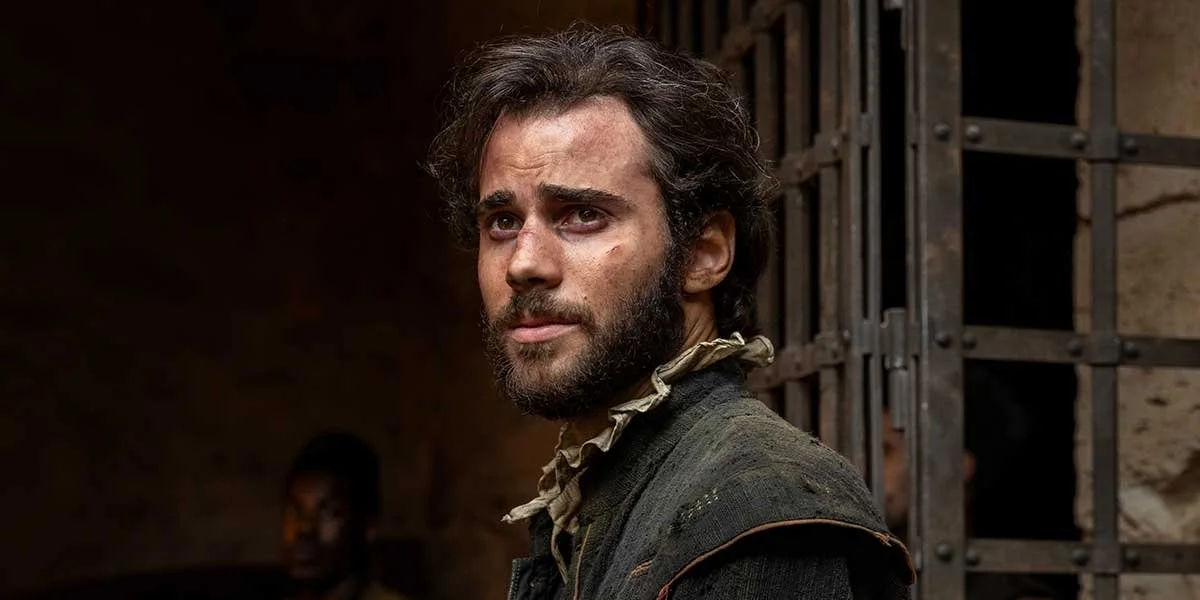

Formally, the film takes place in a future world where humans have discovered they can live forever if they do not dream. But there is a Deliriant (Jackson Yee) who continues to dream, allowing him to reincarnate and shapeshift in a series of cinematic worlds. We follow him through five dreams, told in five vastly different visual styles, each taking place in a different era and thematically tied to one of the five senses.

The extended vignettes aren’t so much about narrative cohesion as they are a kind of dream logic that plays on our memories of films. Bi has conjured a dazzling ode to the century of motion pictures that came before him, his vignettes spanning everything from the silent-film era to film noir and contemporary first-person perspective. Along the way, we get touchstones of 20th-century Chinese history. His labyrinthian world pays tribute to countless auteurs—Hou Hsiao-hsien, Wong Kar-wai, Fritz Lang, the Lumière brothers, and Orson Welles, to name only a few. Bi is also “resurrecting” the creative passion for hands-on filmmaking—a message that resonates in a world of AI and CGI—and reclaiming the power of imagination.

Which segment you prefer may depend on your cinematic leanings. The most stunning may be the opening, with its diorama-like opium den, cutout paper puppets, and hallucinatory stop-motion poppies, or the final vampire love story, with its red neon, pelting rain, and maze-like port-city alleyways. Then again, the shadowy, noir-ish second piece, with its sprawling, bomb-shattered train station, is a marvel, as are the artfully composed, teal-and-red-popped shots of a card shark and his child sidekick in the fourth.

Along the way in this opulent, two-and-a-half-hour work of art, Bi acknowledges that we are watching and celebrating the magic of film together, with the sum of his five chapters greater than any of the separate parts. Dreaming is about surrender, and cinephiles who submit to this phantasmagoria won’t want to wake up. ![]()

Janet Smith is founding partner and editorial director of Stir. She is an award-winning arts journalist who has spent more than two decades immersed in Vancouver’s dance, screen, design, theatre, music, opera, and gallery scenes. She sits on the Vancouver Film Critics’ Circle.

Related Articles

Gourou, Dalloway, and a flick inspired by Liliane Bettencourt of the L'Oréal dynasty help launch 32nd annual fest

Offerings span basketball documentary Saints and Warriors, identity-focused short “One Day This Kid”, and beyond

At VIFF Centre, new Velcrow Ripper and Nova Ami documentary finds women leading residents out of wildfire and flood catastrophes, in Lytton, Yarrow, and beyond

Offerings include features Sirât and Mr. Nobody Against Putin, plus programs for Live Action, Animated, and Documentary shorts

Matt Johnson is back with a chaotic, unabashedly Canadian followup to the cult web series

Visions Ouest and Alliance Française present poignant documentary about a woman retracing her roots to a vibrant but deeply troubled country

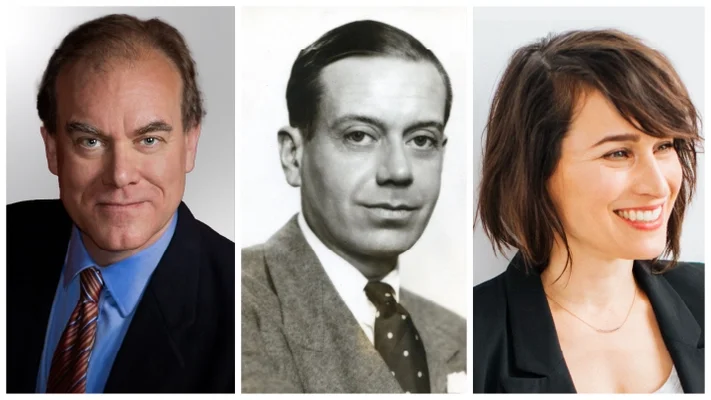

Classic film scholar Michael van den Bos hosts evening that mixes vintage film clips with the jazz sounds of the Laura Crema Sextet

Artists like Dee Daniels, Brandon Thornhill, and Krystle Dos Santos are performing around the city this February

In a short documentary, the Vietnamese Canadian queen reflects on becoming the country’s first drag artist-in-residence

Oscar-shortlisted film takes a sweeping, humanistic look at the toll of decades of violence

Retrospective closes with the Japanese director’s melancholic final picture, Scattered Clouds

Visions Ouest screens raucous tale of women ousted from their Quebec rink and ready for revenge, at Alliance Française

Event hosted by Michael van den Bos features Hollywood film projections and live music by the Laura Crema Sextet

Zacharias Kunuk’s latest epic tells a meditative, mystical story of two young lovers separated by fate

Ralph Fiennes plays a choir director in 1916, tasked with performing Edward Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius

A historical adventure about Cervantes and documentaries about a flamenco guitarist and a matador are among the must-sees at the expanded event at the VIFF Centre

Screening at Alliance Française and co-presented by Visions Ouest, the documentary of the folk-rockers’ rip-roaring 2023 show was shot less than a year before lead singer’s death

At the Cinematheque, Bi Gan creates five chapters, told in vastly different visual styles—from silent-film Expressionism to shadowy noir to neon-lit contemporary

Four relatives converge on an old house, discovering the story of an ancestor who journeyed to the City of Light during the Impressionist era

The Leading Ladies bring to life Duke Ellington’s swingy twist on Tchaikovsky score at December 14 screening

Legendary director’s groundbreaking movies and TV work create a visual language that reflects on some of film history’s most sinister figures—and mushroom clouds

Chandler Levack’s love letter to Montreal and her early 20s offers a new kind of female heroine; Kurtis David Harder unveils a super-energetic sequel; and Wədzįh Nəne’ (Caribou Country) takes viewers to B.C.’s snow-dusted northern reaches

Vancouver visionary behind innovative thrillers like Longlegs and The Monkey is also helping to revive the Park Theatre as a hub for a new generation of cinemagoers

Criss-crossing the map from the Lithuanian countryside to a painful Maltese dinner party, this year’s program provokes both chills and laughs

Titles include Denmark’s The Land of Short Sentences, Ukraine solidarity screening Porcelain War, and more

From Everest Dark’s story of a sherpa’s heroic journey to an all-female project to tackle Spain’s La Rubia, docs dive into adventure

Out of 106 features, more than 60 percent are Canadian; plus, Jay Kelly, a new Knives Out, and more

Event screens The Nest, the writer’s form-pushing NFB documentary re-animating her childhood home’s past, co-directed with Chase Joynt

Featuring more than 70 percent Canadian films, 25th annual fest will close December 7 with The Choral

Filmmakers including Chris Ferguson back plan to save Cambie Street’s Art Deco cinema that Cineplex had shut down Sunday