Russian pianist Mikhail Voskresensky is a rebel with a cause

A guest of the Vancouver Chopin Society, the veteran musician risked it all to stand up against tyranny

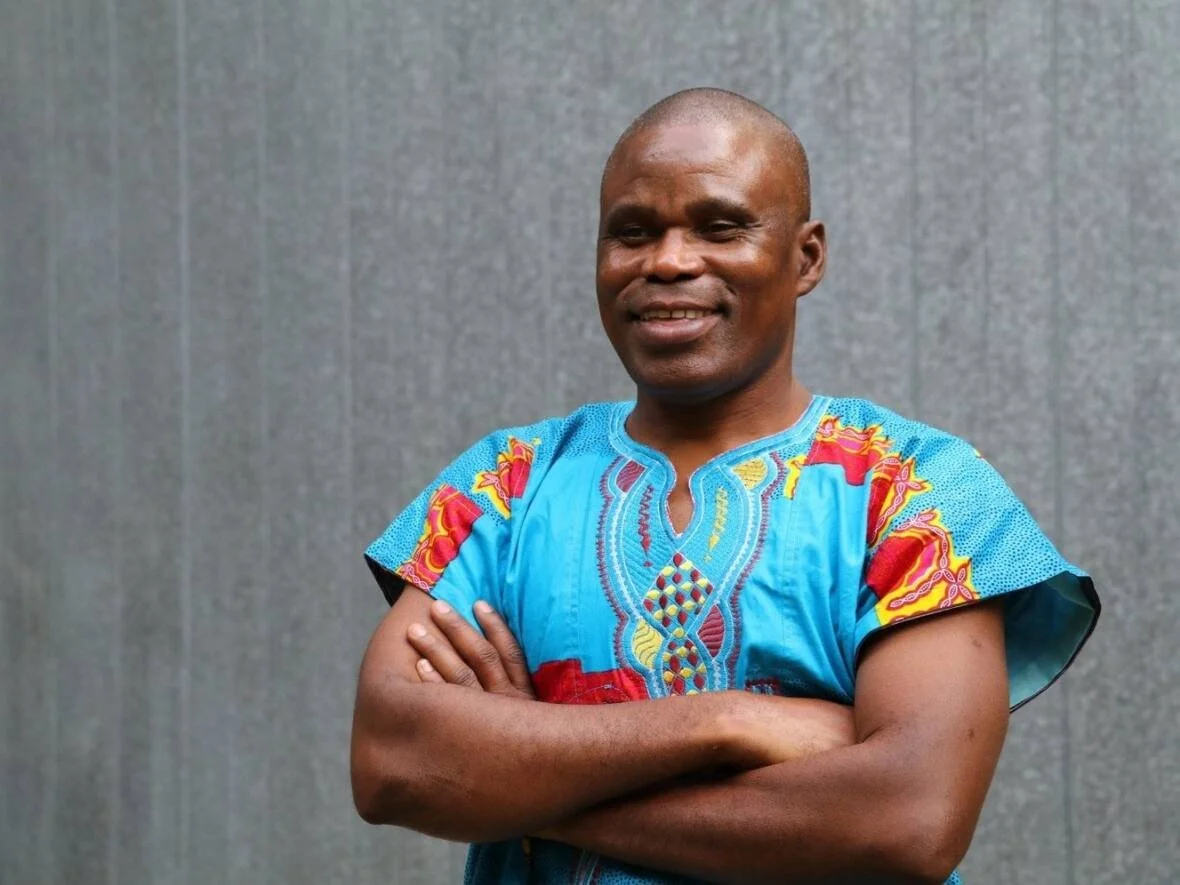

Mikhail Voskresensky.

The Vancouver Chopin Society presents Mikhail Voskresensky at Christ Church Cathedral on May 30 at 7:30 pm

FOR MUCH OF HIS LIFE, the Moscow Conservatory was the centre of Mikhail Voskresensky’s world. The pianist graduated from the venerable institution in 1958, and subsequently spent decades there as chair of the piano department.

He left that post very suddenly in 2022, his spur-of-the-moment resignation a direct response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. He left behind not just his beloved alma mater, of course, but also his home and many cherished colleagues, friends, and relatives.

“I lost everything in one day when I left Russia, but my decision was very, very strong,” Voskresensky tells Stir on a call from New York City. “It was mostly a moral decision. It was an ideological decision.”

Voskresensky is Russian, but his connection to Ukraine runs deep. He was born in Berdiansk, in what is now Ukraine but was, at the time of his 1935 birth, part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union.

He also has indelible childhood memories of the Second World War, which had a significant and devastating impact on his immediate family.

“I lived during this horrible war, and I remember it very clearly all my life,” he says. “My father was killed at the front, in the war. So when my government in Russia began this criminal war against innocent people, for me it was a tragedy, a personal tragedy. I could not accept it. And for me, there was only one decision. I could not go to the street with the protest; it was senseless. But I understood that I cannot live in a country that’s killing innocent people.”

To remain in Russia, Voskresensky felt, would make him complicit in an illegal invasion and the subsequent war, which continues to this day. He decided that he needed to leave the country, but he wasn’t sure who might be able to assist him in making that a reality. “It was very difficult,” he says, “because I had many of my former pupils who lived abroad, but all of them told me, ‘Well, we understand you, but we cannot help.’”

Fortunately, Yoheved Kaplinsky, chair of the piano department at the Juilliard School, secured an invitation for Voskresensky to perform at that year’s Aspen Music Festival in Colorado, which allowed him to get a visa, enabling him and his family to leave Russia. They now live in the United States.

Even when the current war ends, as all wars must, Voskresensky says there’s only one thing that would convince him to go back: regime change. The pianist knows full well how much of a risk he has taken in speaking out against the government of Vladimir Putin. Because of that, he doesn’t blame his peers back in Moscow for keeping their silence.

Mikhail Voskresensky.

“Some of my colleagues supported this war; some, I’m sure, did not, but they didn’t speak up because it is dangerous,” Voskresensky says. “In my opinion, the inhabitants of Russia are now in a very difficult situation. They can’t express their thoughts if they are not the same as the official propaganda. So it is a very difficult life there, and I know many of my friends who feel this very much.”

Living in North America has advantages beyond its relative safety. It has given Voskresensky the opportunity to perform in new places—including Vancouver, where he’ll make his local debut at Christ Church Cathedral on May 30.

On the program are Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 25 in G major, Op. 79; Mozart’s Fantasia No. 2 in C minor, K. 396; two selections from Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons; and Grieg’s Piano Sonata in E minor, Op. 7.

And it simply wouldn’t do to leave Chopin off the list. Voskresensky is, after all, performing here as a guest of the Vancouver Chopin Society, and he has a long history of personal connections to the Polish composer. In his conservatory days, Voskresensky was a student of the great Soviet pianist Lev Oborin, who won the very first Chopin International Piano Competition in 1927. Later, Voskresensky himself began his professional career by playing Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 with the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra under the baton of Yevgeny Svetlanov.

In Vancouver, Voskresensky will play Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 3 in B minor, Op. 58, which is widely regarded as one of the composer’s most technically challenging pieces.

“This is a very well-known composition, but I think it is a very interesting composition,” the pianist notes. “It was written in the last 10 years of his very short life. I will try to show that the soul of Chopin was very rich in feelings, very rich in thought, very rich in tragedy, and in spite of tragedy, this composition finishes in a major key.”

Indeed, the finale is a sonata-rondo, which the composer marked Presto, non tanto, and it closes with a rousing coda in B major.

Given the pianist’s own history, it’s hard not to notice parallels to his own journey in Chopin’s composition, which, though rooted in tragedy, wraps up on a rousing note of triumph.

Not that Voskresensky is about to wrap anything up. The pianist, who turns 90 next month, has no plans to slow down in the near future. Or ever, for that matter.

“No!” he says joyfully. “I don’t think about retirement, because I’m full of energy. I don’t feel my age, and I play a lot of concerts. The day before yesterday, I played a recital in New York. The day after tomorrow I go to Philadelphia and I will play with the Philadelphia Chamber Orchestra; two concertos by Mozart in one evening.”

Voskresensky may have several decades on the likes of Pussy Riot, but he clearly shares their rebel spirit, standing up not only to authoritarianism but also to old age.

“We are soldiers of culture and will die on the stage!” he announces.

Take that, Putin. ![]()