Composer Kati Agócs reveals sacred music as source of resistance in Hosanna of the Clouds

Vancouver Bach Choir performs Canadian premiere of work that draws on both ancient tradition and the 20th-century avant-garde to explore the creative act

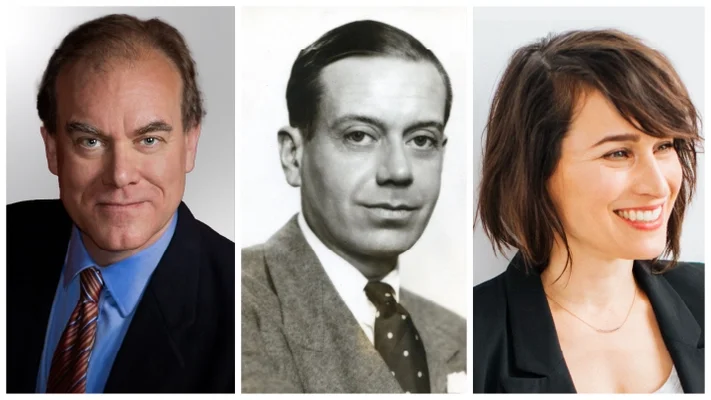

Kati Agócs

The Vancouver Bach Family of Choirs presents Hosanna of the Clouds at the Orpheum on February 28

PALM SUNDAY, WHICH this year falls on March 29, has to rank as one of the least celebrated occasions in the Christian liturgical calendar, al least in the sphere of music. Traditionally hailed as the day on which the mystic and radical Jesus Christ entered Jerusalem as the long-promised Messiah, it has been overshadowed by the events that took place five and seven days later, when Christ was martyred and then seemingly rose from the dead. Nominally a time of celebration, its import has been occluded by hindsight, and of the great liturgical composers in the Western tradition only Johann Sebastian Bach has limned it in song, with his joyous cantata Himmelskönig, sei willkommen.

Until now, that is. Recognizing a gap in the liturgical songbook, Canadian composer Kati Agócs has thrown her Hosanna of the Clouds into the ring—not that she aims to compete in any way with her illustrious forebear. Bach, she explains, is her primary compositional influence, and can never be excelled. She does hope, however, to join the ranks of more contemporary composers of sacred music, citing Olivier Messiaen, Igor Stravinsky, Sofia Gubaidulina, and Arvo Pärt as older peers that are close to her heart, even if they never chose Palm Sunday as their topic.

“I do best when I write for specific occasions and specific performers, and I realized that there aren’t many works for Palm Sunday,” the Ontario-born Agócs explains, in a telephone interview from her Massachusetts home. “There’s the Bach piece but there’s really little else, so I decided that I wanted to fulfill that purpose and contribute something.”

The Boston Modern Orchestra Project’s artistic director Gil Rose agreed, and commissioned Hosanna of the Clouds. The Vancouver Bach Choir, under the direction of conductor Leslie Dala, will give Agócs’s piece its Canadian premiere at the Orpheum on February 28, in a pairing with feminist pioneer and composer Dame Ethel Smyth’s Mass in D major.

It’s a welcome return to British Columbia for Agócs, who counts among her mentors two now sadly deceased residents of this city, former Vancouver Symphony Orchestra music director Bramwell Tovey and the remarkable composer Jocelyn Morlock.

Agócs describes herself as “a Christian humanist”, and throughout her career has balanced music in church with negotiating the secular arts. The choral setting is not foreign to her: she’s sung in choirs all of her life, and studied voice with the American soprano Adele Addison. But she’s also performed avant-garde works by Bang on a Can cofounder Julia Wolfe and others, and that shows in her adventurous use of harmony, which in Hosanna of the Clouds seems to grow in complexity and daring as the work itself builds in emotional heft.

With this sacred work, that’s intentional. “It’s important to think about the meaning of the word ‘hosanna’, because I use that in three different places in the piece, as structural pillars,” Agócs explains. “It starts the piece, and then in the third movement it comes in as a refrain after the soprano solo, and then it comes in in the sixth movement as a sort of big, grand recap. And so ‘hosanna’ is both a prayer and an exclamation of worship, meaning ‘praise, joy, or adoration’. But it also asks for help. From the Hebrew for ‘Give us salvation now,’ it’s a petition for deliverance from oppression, sin, or trouble, and a heartfelt one.

“I think the soprano functions in the piece as a proxy for me, sort of a surrogate or stand-in for me,” she continues. “Like, my thoughts, my feelings, my transformation. So in the third movement her voice is intimate; it’s just her and God. And in the fifth movement it’s an aria saying, ‘Look, He’s coming. He’s here!’ But in the sixth movement, in which she sings over the ‘Hosanna’, she’s transfigured into the voice of God, and she’s actually saying, from the Bible, ‘I am the alpha and the omega.’ But that’s God saying it.”

Agócs is far too modest to claim divine power, but she allows that in all of her work she’s seeking divine inspiration, however that’s construed. Sometimes she finds the numinous in Christian symbolism; sometimes in the calming effects of immersion in the natural world. It’s telling, perhaps, that she spends her summers in Newfoundland, far away from the bustle of academic life and the metropolitan pressures of Boston, where she teaches at the New England Conservatory of Music. Being in nature, she says, allows for the experience of grace, as does the act of writing music and then bringing it to life in the concert hall—or in the nave of a cathedral.

“Sacred music I think of as a life force; it’s like in every cell,” she says. “So many of my works come from a faith impulse; it’s where my heart is, and it’s how I originally started writing concert music. But I also don’t see it as ‘You have to be in this one tradition to understand it or to feel it.’

“And it’s an act of resistance to live a life dedicated to the musical arts,” she adds. “It’s important for us to take a stand as artists and to enter deeply into the act of creating and the social aspects too, the collaborative aspects. That can be a political act.”

Agócs may be immersed in an inherently conservative milieu, but she’s determined to infuse it with contemporary relevance. Hosanna of the Clouds is sung in three languages, including Latin and Aramaic, but the composer notes that her use of English toward the end is both musically apt and intentional. “That’s the most direct passage, and it’s saying, ‘Make room for grace. Make room for devotion. Make room for something greater inside us, or between us.’

“That’s the universal message of the piece,” she adds. It’s perhaps a sad commentary on our times that something so benign can be construed as a statement of revolt, but in an age of institutional cruelty Agócs’ stance is also clearly necessary. ![]()