Stir Q&A: Tree canopy ecologist Nalini Nadkarni gives ground-bound humans a look at lush life forms above our heads

Her National Geographic Live event From Roots to Canopy lands in the Lower Mainland care of Vancouver Civic Theatres

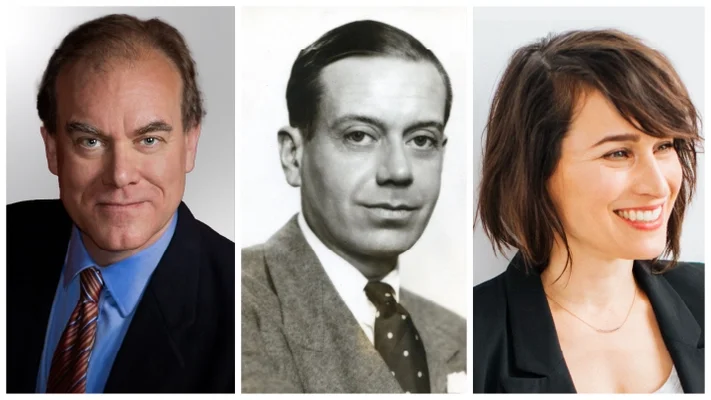

Nalini Nadkarni of From Roots to Canopy. Photo courtesy of National Geographic Live

Vancouver Civic Theatres presents From Roots to Canopy at the Vancouver Playhouse on October 15 at 7:30 pm, as part of the National Geographic Live series

RAINFORESTS ARE USUALLY divided into four layers from bottom to top: the forest floor, the understory layer, the canopy layer, and the emergent layer.

It’s the canopy, which is made up of densely overlapped tree branches and leaves, where the majority of rainforest life forms thrive. And it’s also the canopy that captured the attention of Nalini Nadkarni, one of the world’s foremost tree canopy ecologists, when she was first beginning her scientific career more than four decades ago.

Nadkarni is now a National Geographic Explorer at Large. Considered the highest distinction within the organization, it’s given out to folks who are mentors and ambassadors, continuously acting as leaders in their field and sharing their findings with the public. Nadkarni will be visiting the Vancouver Playhouse on October 15 as part of a series called National Geographic Live, care of Vancouver Civic Theatres. She’ll be teaching audiences about her fascinating research through photography, video footage, and spoken-word stories.

Stir touched base with Nadkarni before the event, called From Roots to Canopy, to learn a bit more about her work.

From Roots to Canopy. Photo courtesy of National Geographic Live

What you remember of your very first trip to Costa Rica to explore the rainforest canopies there? What kinds of feelings and thoughts wash over you when you find yourself amid a canopy?

It was on my first trip to Costa Rica—as a new graduate student on a field ecology class—that I first made acquaintance with the tropical rainforest canopy. Although I had climbed trees for fun as a kid on the East Coast of the U.S., I had no idea of the richness and abundance of canopy-dwelling animals until my walk through the cloud forest of Monteverde. There was so much beauty and life and activity going on high above our heads—birds feeding, monkeys howling, orchids blooming—and all of it nearly out of sight from us ground-bound humans.

When I expressed interest in exploring that part of the forest, my professors were discouraging, because there were no safe or nondestructive ways to gain access to the canopy, and carrying out ecological studies without actually being up there would be impossible. Happily, I encountered a pioneer of forest canopy access, Don Perry, during that class, and he taught me how to ascend into the crowns of tall trees using mountain-climbing techniques.

During my early climbs, I was thrilled to be surrounded by the three-dimensional volume of the forest, to see views from the tops, and to encounter plants and animals that had never been studied. Even now, after 42 years of climbing trees, I get the same sense of excitement and wonder of “What will I discover today?”

In all your time studying and exploring tree canopies, which of your discoveries has been the most personally fascinating to you? What has sustained your interest in and concern for tree canopies over the years?

The most surprising discovery I made was the long length of time it takes for canopy-dwelling plants to recover and grow back after they are physically disturbed. Starting in 1987, I carried out experiments that involved removing patches of canopy-dwelling plants from branches and trunks, and had expected them to grow back quickly, since they look so lush and diverse. But it took nearly two decades for anything to grow back—and now, nearly 40 years later, those “disturbed” canopy plant communities have not returned to their former state. This helped me understand that rainforest communities are fragile and vulnerable to disturbances even if they look strong and vibrant. It guided me to study other disturbances, like the effects of forest fragmentation and climate change, on rainforests.

Nalini Nadkarni. Photo courtesy of National Geographic Live

What is the importance of canopy plants within whole ecosystem processes?

Although the quantity of canopy plants is quite small compared to the biomass of the forest as a whole (10 to 15 percent in tropical forests), they play important roles in many forest processes. Because they do not have access to water and nutrients from their supporting trees, nor from the soils of the forest floor, they have adapted to intercept and retain nutrients that are dissolved in mist and rain, which comes from outside the ecosystem. They hold on to those nutrients for some time, and then, when they fall to the forest floor, those nutrients are circulated to other plants rooted in the forest floor. So the canopy plants swell the total amount of nutrients available to the whole forest. Canopy plants also supply a large amount of food and habitat resources to birds, arboreal mammals, and invertebrates, such as nectar, fruits, and nesting materials.

What are some of the plants, animals, and microbes you’ll teach audiences about during your upcoming presentation of From Roots to Canopy in Vancouver?

I will describe the intimate relationships between canopy-dwelling organisms and the trees that support them. Among those are some of my own favourites, like the delicate orchids that are pollinated by specialized bees; and the bromeliads (relatives of pineapples!), which support populations of tadpoles that grow into frogs and are hunted by canopy-slithering snakes. I’ll also illustrate the unique “canopy soils” that are created by decomposing canopy plants, and which cover branches and trunks, harbouring a habitat that fosters thousands of invertebrates and microbes who live their entire lives aloft, separate but connected to the forest floor. And I’ll show images of some of the birds and arboreal mammals we encounter in the canopy—colourful hummingbirds, slow-moving sloths, and branch-walking anteaters.

How does the basis of what you’re covering apply to the rainforests here in British Columbia?

Although the species of canopy organisms in the tropical cloud forests where I work in Costa Rica [vary] from the canopies of British Columbia, the nature of the canopy is very similar—it fosters biodiversity, as there are many plants and animals that live in B.C. canopies that are not seen on the forest floor, just as in tropical forests. In both habitats, canopy-dwelling biota play important ecological roles in the cycling of nutrients and water on an ecosystem-level basis. And in both types of forests, the canopy provides beauty and a sense of connection to all parts of the forest.

Just as in the tropics, awareness of trees and their importance to people and other elements of nature applies to everyone, everywhere, including British Columbia. The province has over 60 million hectares of forested land, about 60 percent of its total land area. Vancouver is a city with great urban tree cover—one of the highest in Canada—and local and regional parks that people can visit and enjoy.

Groups like Tree Canada, a national nonprofit organization, are dedicated to planting and nurturing trees in rural and urban environments, in every province across the country, so people can join that and participate in its activities. People can get information from places like the Metro Vancouver Tree Regulations Toolkit to plant and care for trees in optimal ways. Donating funds to regional, national, and international groups like the Nature Conservancy of Canada can amplify efforts. And just noticing and talking about the trees around you with neighbours, friends, and strangers can raise awareness.

What sort of impact has being a National Geographic Explorer at Large had on your life and career?

Being a National Geographic Explorer at Large has provided a huge and wonderful boost to my work and my life. It provides resources that I can use to expand the reach of what I am passionate about doing—understanding trees and sharing that knowledge with other people. It has given me access to other National Geographic Explorers so that we can collaborate on projects that we formerly worked on individually, which strengthens the tapestry of our hope to illuminate and protect the natural world. And it has provided me with a pathway to start “The Our-Trees Initiative”, a storytelling-based program to raise awareness and incite actions on the part of trees around the world. ![]()