Dance review: From mourning to solace, Eternal Gestures honours emotions we feel for the land

Co.ERASGA’s Alvin Erasga Tolentino performs three solos by Indigenous choreographers Starr Muranko, Margaret Grenier, and Michelle Olson

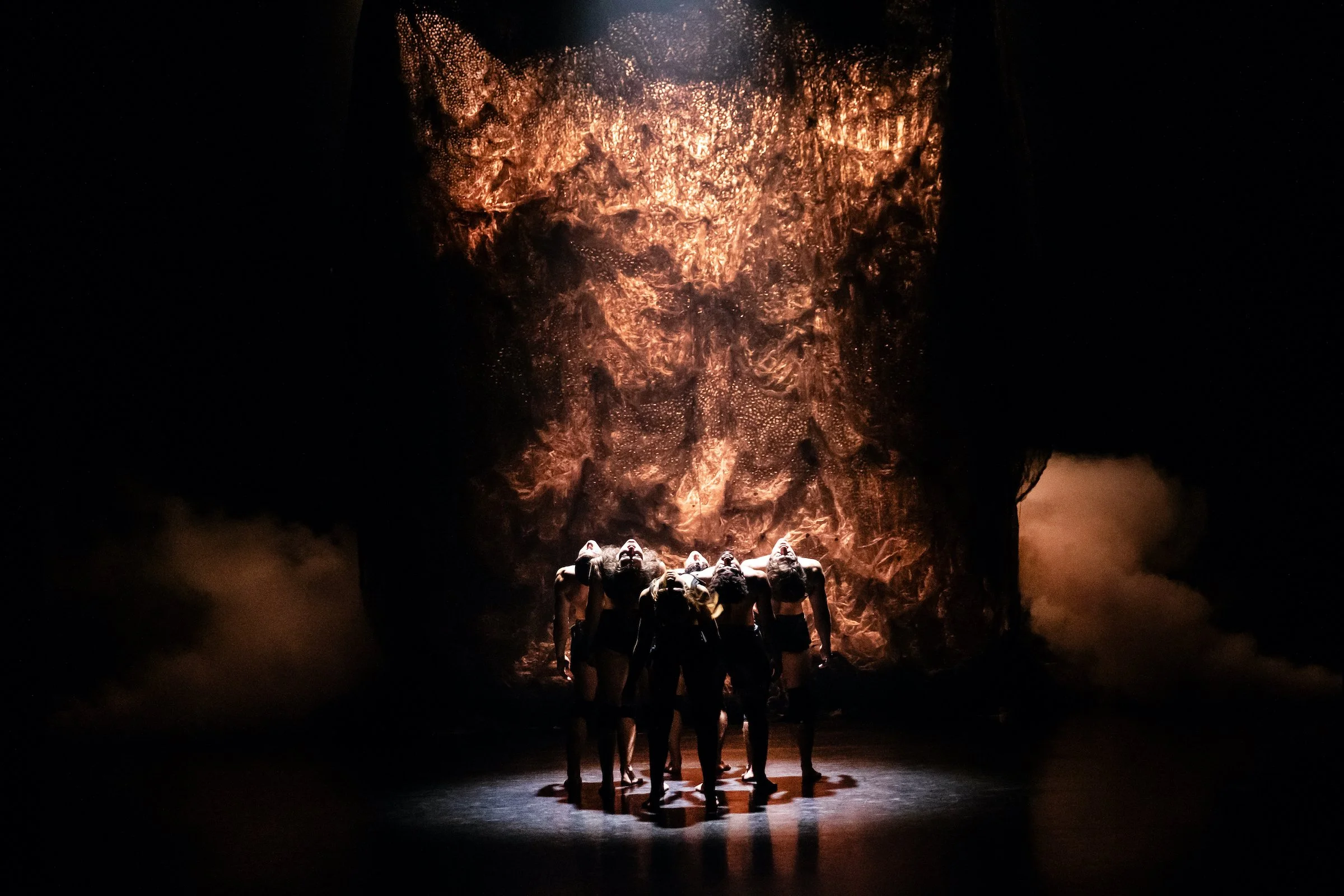

Alvin Erasga Tolentino in Eternal Gestures. Photo by Yasuhiro Okada

The Dance Centre presented Co.ERASGA’s Eternal Gestures on October 9 and 10 at the Scotiabank Dance Centre

ANCESTRAL CONNECTIONS TO LAND are at the heart of Eternal Gestures—and in one of the production’s first intimate sequences, dancer Alvin Erasga Tolentino demonstrates that with pride.

Positioned at the front of the stage, the Co.ERASGA founding artistic director scoops his hands into a woven basket filled with rice, then lifts them up and lets the grains spill softly back into their vessel while he recites an earnest monologue to the audience in Tagalog. Though there is no translation, it feels as though the artist—who was born in Manila and immigrated to Canada in 1983—is recounting a fond memory of his homeland.

The scene is part of “Tahanan/Home” by Starr Muranko, one of three back-to-back solos choreographed by Indigenous women and performed by Tolentino. The work sets the tone for what’s to come in a compelling program brimming with tender hand gestures and deeply thought-out layers.

Many of Tolentino’s movements throughout the three solos feel methodical. There’s the slow, controlled banging of his fists against the stage floor; the heavy, rhythmic stomping of his bare feet; the scooping of his arms up and over his head. Scenes of labour are a well-chosen nod to how people around the world connect with and live off the land—tilling soil, planting seeds, harvesting crops. Tolentino enacts each of those processes with precision and near-ritualistic dedication.

At one point in Muranko’s solo, the voice of the choreographer, who is of mixed Moose Cree First Nation, German, and French ancestry, sounds out over the speakers. She reminisces on her years-long friendship with Tolentino, referencing cherished moments like “slow, sunshine-filled walks”, as he kneels peacefully in the warm beam of a spotlight. Elsewhere, Tolentino holds up a long, thin tree branch, twisting it through the air with reverence.

That branch makes another appearance in the third solo of the evening, “Lu skhl ‘nitdinsxw - embodied responsibility” by Margaret Grenier, who is of Gitxsan and Cree ancestry. This piece feels more hopeful, like the break of dawn; birds are chirping, water is trickling, and bright-white light is shining as Tolentino raises his arms to the sky. There are feather-light vocals by Raven Grenier, Margaret’s daughter, who also recites a poem called “Our Mother the Earth” by Duke Redbird, an elder from the Saugeen Ojibway Nation. And with music by Tolentino’s longtime collaborator Emmanuel Mailly, the solo feels like a warm hug.

Alvin Erasga Tolentino in Eternal Gestures. Photo by Yasuhiro Okada

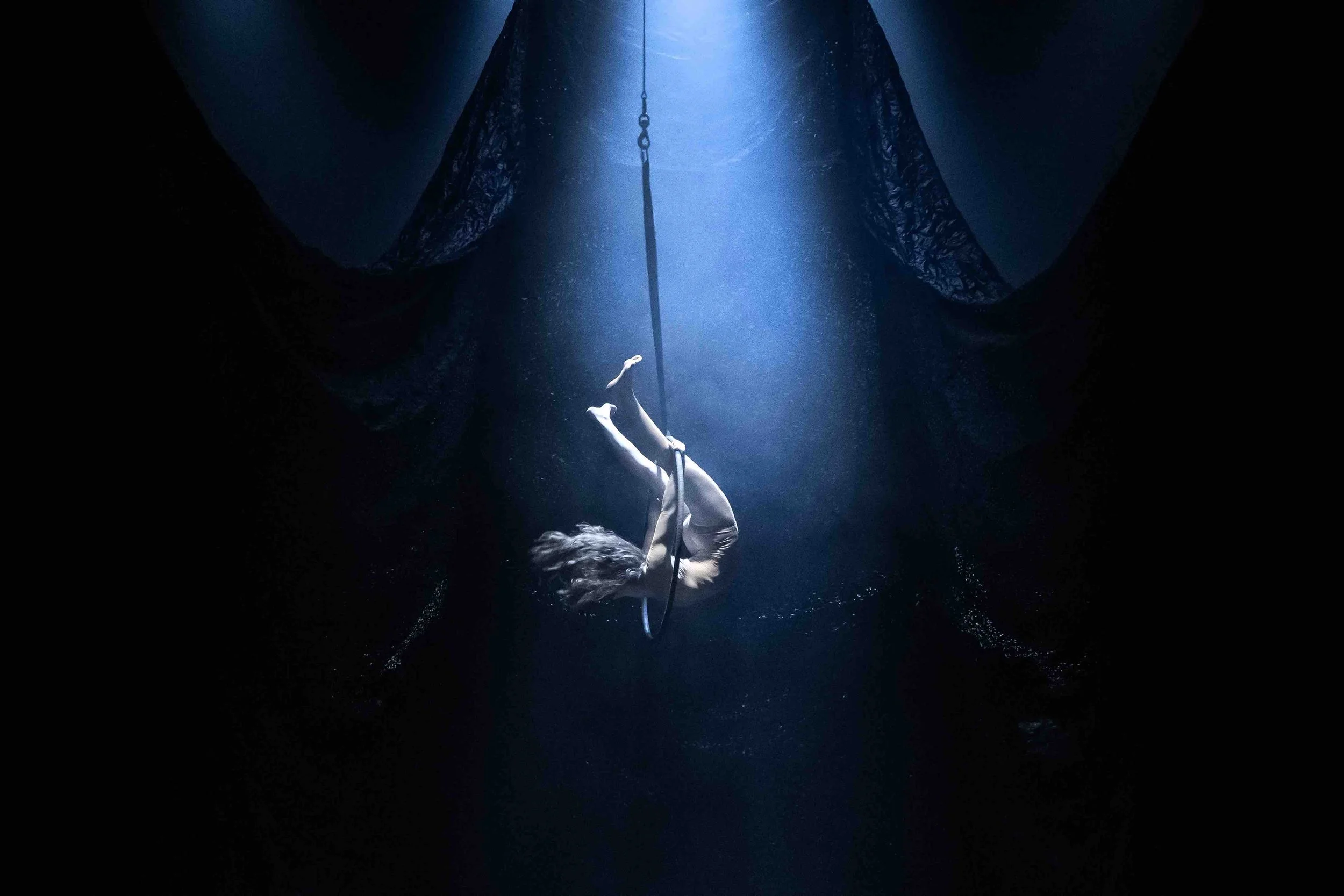

By contrast, Michelle Olson’s solo “unsurrendered”—bookended by Muranko’s and Grenier’s with only a minute-long darkening of the lights in between—feels more volatile. The piece by the matriarch from Yukon’s Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation features a soundtrack by Inuk throat singer Tanya Tagaq and Cree musician Jessica McMann. Tagaq’s vocals start off mournful. Drawn-out wails echo over the theatre, soon giving way to guttural moans, then horror-filled cries, then angry, ripping snarls. Tolentino convulses onstage as white lights flicker rapidly; then the room is plunged into a blood-red glow.

In a short span, we’re transported from grief to fury to, eventually, solace, as the lights turn a soft blue and Tagaq begins to hum soothingly. When the words “STOLEN LAND” are projected onscreen, all the pieces click into place.

Videographer Yasuhiro Okada has designed other projections that appear throughout the show, too; in “Lu skhl ‘nitdinsxw - embodied responsibility”, Gitxsan words are translated into English for the audience, and we learn that “yip”, for instance, means “land”. It’s worth noting that the projections aren’t too distracting, and the stripped-down set design really allows for the movement and soundscape to shine.

What comes across most throughout Tolentino’s masterfully delivered performance is that caring for the land is ultimately a labour of love. Though we all have different relationships to the land, it is each person’s responsibility to acknowledge, cherish, and protect what gave life to the generations that existed before us—and the ones that are yet to come. ![]()