Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s T’əl: The Wild Man of the Woods braids Indigenous storytelling with classical dance

Rising Tla’amin choreographer Cameron sinkʷə Fraser-Monroe draws on a tale he heard growing up for a large-scale work that joins Carmina Burana on a double bill

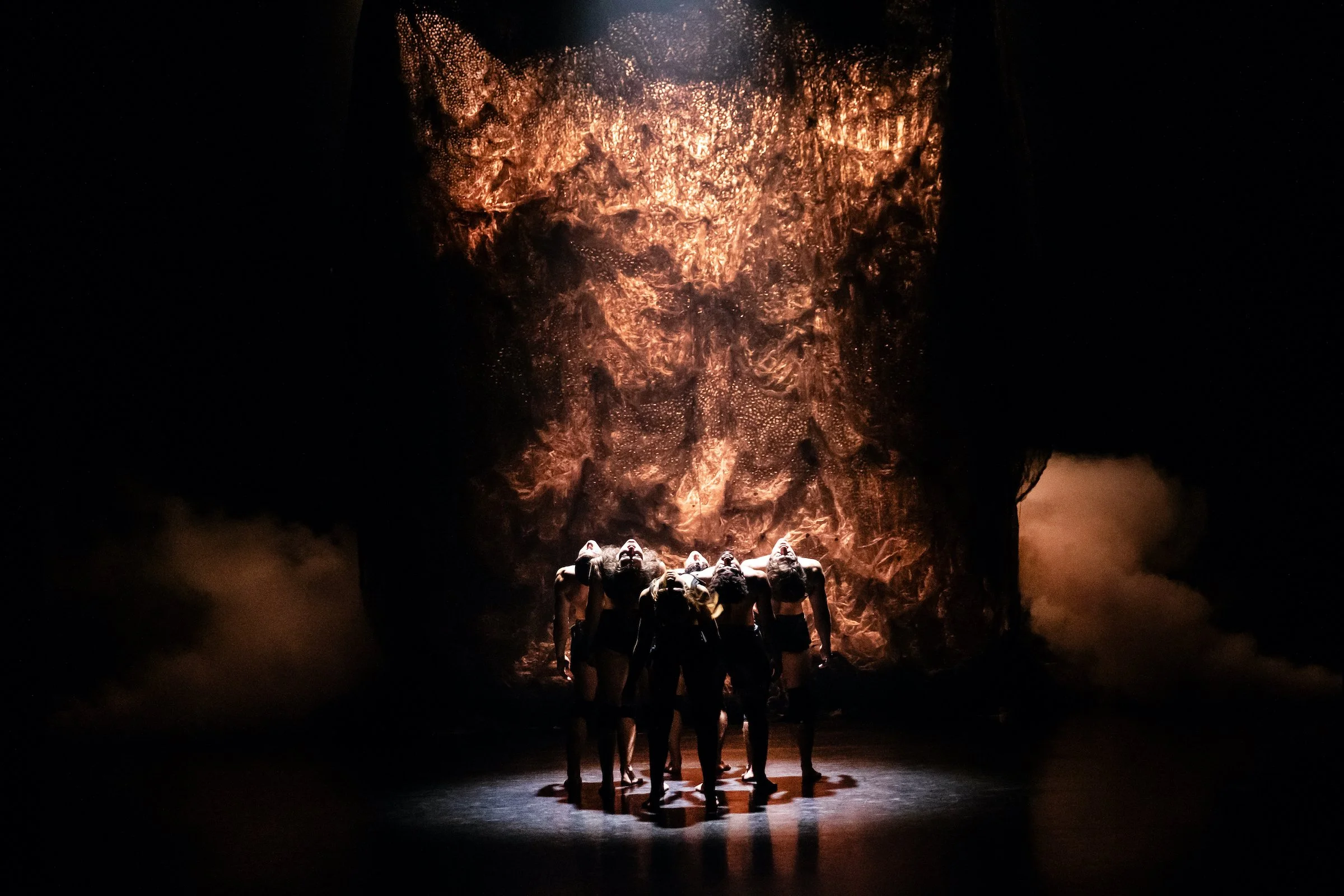

T’əl: The Wild Man of the Woods. Photo by Daniel Crump

The Royal Winnipeg Ballet performs Carmina Burana and T’əl: The Wild Man of the Woods at the Centre in Vancouver on February 9 and 10

WHEN HE WAS LITTLE, Cameron sinkʷə Fraser-Monroe was told the story of T’əl, the wild man of the woods who steals children at night. A member of the Tla’amin Nation, he would pass on the story—equal parts scares and laughs—to his younger cousins as he got older. And now, in a development he might never have predicted as he listened to the tale as a child, he’s bringing it to the stage as a large-scale ballet, joining the Royal Winnipeg’s signature Carmina Burana in Vancouver next week.

“Of course I was afraid of T’əl—I think we all were!” he tells Stir with a laugh, speaking on a Zoom call from tour rehearsals at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, where he also studied and performed. “You would hear it growing up in maybe the same way you would hear about Santa Claus. But part of the reason I was really drawn to this story when it came time to choreograph it is that it’s not only entertaining. It’s also used as a tool. It’s something that has kept our children safe for hundreds of years, kept us inside before dark, and kept us behaving. And part of the beauty of it is it’s quite intergenerational.”

The tale of T’əl: The Wild Man of the Woods is also, in a way, universal—which is one of the reasons the rising young artist turned to the oral-storytelling favourite while he was choreographer in residence at the RWB.

“When it came time to choreograph a ballet, it speaks to a number of people,” he says. “It doesn't matter what culture, what region of the world you’re in, whether it’s the yeti or the sasquatch, there’s always a hairy man in the woods that we talk about around fires after dark. Something that really spoke to me was the fact that it was culturally specific to the Tla’amin Nation and also universally.”

Rather than try to put his own twist on the story, Fraser-Monroe returned directly to the source, reaching out to 94-year-old Tla’amin Elder Elsie Paul, who kept the oral history alive through potlatch bans. In the ballet production hitting the Centre in Vancouver, she narrates in both her native Ayajuthem and English. The Indigenous-led creative team for T’əl: The Wild Man of the Woods also includes an original score by 2-Spirit cellist-composer Cris Derksen, and costumes with warm cedar hues by New York–based Navajo designer Asa Benally. Counting the dancers, Fraser-Monroe figures the massive undertaking encompassed around a hundred collaborators in all.

In contrast to traditional narrative ballets, the work doesn’t focus on a love story, but instead follows a fearless girl setting out on a journey to save her sister from the wild man of the woods.

Fraser-Monroe brings a unique take on classical ballet, the rigorous form he trained in at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet School from the age of 15.

Cameron sinkʷə Fraser-Monroe. Photo courtesy Royal Winnipeg Ballet

“Ballet is a colonial art form, and it’s quite interesting to look at the ways that it’s been used throughout history to share European culture,” he begins. “I think of Shakespeare as well, the way it’s been used as an example of a higher art form, or something that should be more appreciated. And I think what’s interesting about this work is I am not always able to decolonize ballet—I’m not trying to take that out. I’m using ballet as a tool in the same way that Indigenous artists now can use MacBook computers to create art and deserve access to these latest technologies. And so for me, ballet is really the lure to get audiences into the house, and to see a story that might be unfamiliar to them, but see it in a very familiar form.

“I like to talk about my style as braiding,” he adds. “It brings together the traditional First Nation sense, the contemporary experience as a professional dancer and the classical ballet into one.”

That unique take is the result of years of diverse practice. At just three years of age in Vernon, Fraser-Monroe began studying Ukrainian dance, and went on to train in everything from traditional grass dance to hoop dance. After going to the RWB School, he performed with companies including B.C.’s Dancers of Damelahamid and the Atlantic Ballet Theatre of Canada. Amid all that, he’s also studied at the Toronto Actors Studio. And now his choreographic work has taken him to troupes such as the National Ballet of Canada and Ballet Kelowna.

Along the way, he’s found inspiration in ballet-trained Indigenous dance artists like Santee Smith and Margaret Grenier. And he’s learned to develop his voice as an Indigenous artist.

“I think, like many Indigenous choreographers, when I talk to them, there was an element of dissatisfaction,” he reflects. “I was tired of seeing our stories told without our voices present. Narrative sovereignty is something I’m very passionate about. And so this project didn’t feel like we were charting a completely new course; it felt like me improving things in the ways that I wanted to see them expanded.

“Sometimes it is hard to be one of very few Indigenous dancers and choreographers present in the work, and it means that we’re pulled in very many different directions,” he adds. “We can’t just be an artist or a dancer. We need to help with policy and we get pulled into all of these other areas. It’s good to come back to your ‘why’, just like in any career choice. And for me, sharing these stories has been incredibly fulfilling.”

He welcomes the chance to place the T’əl story on a bill with a signature work in the RWB’s repertoire, 2002’s Carmina Burana—Mauricio Wainrot’s bold, physically charged interpretation of Carl Orff’s thunderous cantata.

Fraser-Monroe is even more excited to share the work on this B.C. tour, which kicked off last week with a sold-out run in Powell River, where Paul got to see the piece live.

Watching the story unfold as a ballet has been a thrill for the young artist.

“When I’m sitting in the house, Elsie Paul is telling this story about a monster that kidnaps and roasts children to eat them, and everyone is on the edge of their seat,” he relates. “Everyone is leaning in, trying to hear these words, and then a couple times, we all just burst out laughing, because humour is also really at the core of this story. It’s not just this grim fairy tale—there is an element of levity in the work. And as we say, laughter is the best medicine.” ![]()

T'əl: The Wild Man of the Woods. Photo by Daniel Crump