In The Brutal Joy, Justine A. Chambers channels the overwhelming beauty of Black living

With staging that evokes a Chicago jazz bar, the Dance Centre and PuSh Festival co-presentation draws on matrilineal fashion and line dancing

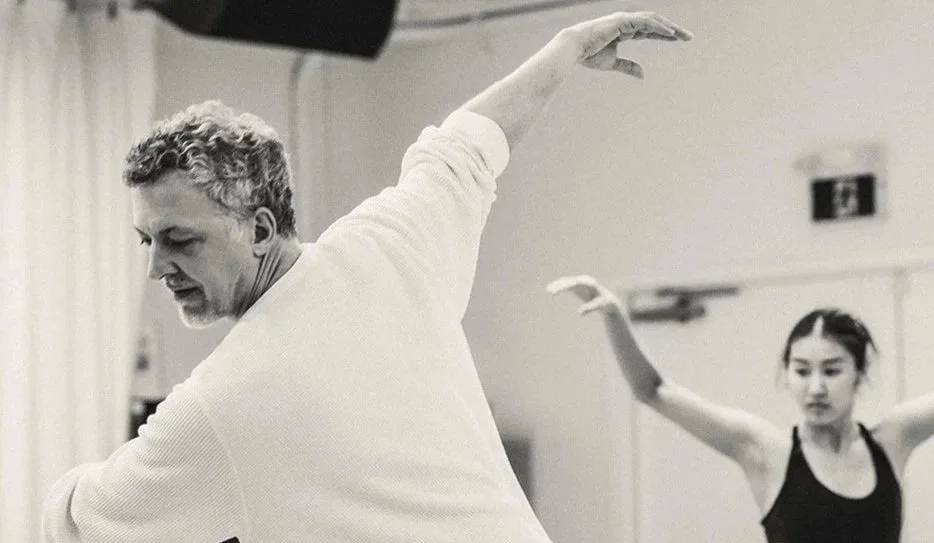

Justine A. Chambers in The Brutal Joy. Photo by Rachel Topham

PuSh International Performing Arts Festival and The Dance Centre present The Brutal Joy on February 5 and 6 at the Scotiabank Dance Centre

JUSTINE A. CHAMBERS GETS her sense of style from her Black matrilineage.

Her mom, a cutting-edge fashionista, used to pick her up from school in the ’80s wearing a sweeping black leather trench coat—over a decade before Morpheus from The Matrix made them cool—with a pillbox hat on and bones braided into her long hair. Her grandmother had a long-lasting affinity for all things fabulous, from pointed-toe heels to costume jewellery. Colourful bottles of nail polish lined her dresser, and the smell of acetone would fill the family’s home on Friday nights as she painted on her manicure. Then there was her intimidating great-grandmother, who kept a pair of pristine silk Pucci shoes tucked away in a box in her closet, and displayed her impeccably styled wigs on Styrofoam heads in her bathroom.

Speaking to Stir by Zoom, Chambers notes that the parts of her own wardrobe she holds closest—like a massive pair of Nefertiti earrings that belonged to her grandmother—can be traced back to the sense of sparkling individuality that her matriarchs embedded in her.

“My dad’s side of the family is also very fashionable,” the biracial dance artist acknowledges, “but there’s a sort of Black sensibility that includes colour and silhouette that is just more fabulous, you know? And for me, there’s such joy in that kind of self-expression, of not just being put together, but being fly, right? It’s just tight. I think there’s something about it being audacious without being tacky….And this courage to be bold in how you present in the world, that’s a way of being seen. Whether people like how they see you or not, it doesn’t matter.”

Chambers channels that relationship to style in her new piece The Brutal Joy, showing at this year’s PuSh International Performing Arts Festival, in a co-presentation with The Dance Centre. Onstage, she’ll be outfitted in a custom workwear suit designed by her friend Cassandra Bailey of Old Fashioned Standards that’s made from waxed cotton, a choice Chambers describes as “speaking back very gently” to the plantations of the American South.

The dance artist explains that the suit (and her relationship to style in general) is also tied to Black dandyism, a cultural movement that involves wearing bold clothes as a revolutionary form of self-expression. (As fashion enthusiasts will recall, last year’s Met Gala theme was “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style”, which paid homage to the movement’s history.) Impeccable dress was a way for African Americans to reclaim power and bodily autonomy post-Emancipation; and the identity-affirming role that fashion plays in Chambers’s life today is anything but coincidental, she notes.

“We can make that a trivial thing,” she says. “But, of course, when you’re a person of colour, nothing you do is trivial. You are both deeply invisible and hypervisible at the same time. So I just wanted to look at that a little bit more closely—because if you know me, you know that fashion is my thing, right? And I was like, ‘Why is that? And why is that so important?’ I just needed to spend some time with that.”

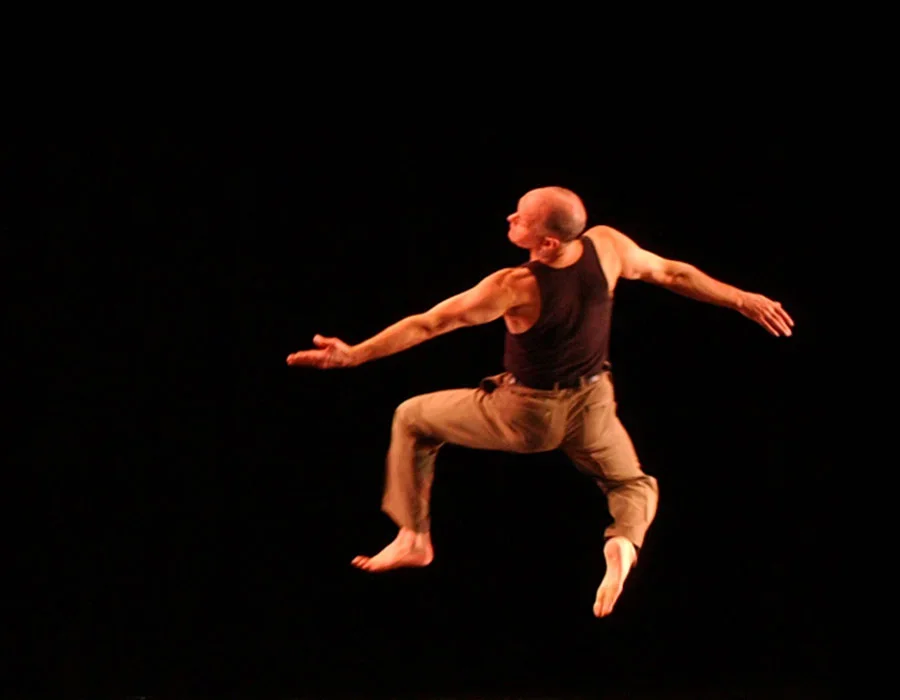

The Brutal Joy. Photo by Rachel Topham

With Chambers’s matriarchs hailing from Chicago, there’s an especially personal angle to it all for her. Growing up, she would spend her summers in the Midwestern city’s all-Black neighbourhoods, which she describes as a “cultural mecca”.

“I wasn’t looking at the contrast between Black and white,” she explains. “I was just revelling in the saturation of Black culture, in my eyes and in my nose and in my touch….That was the place where I felt the most myself, or tapped into a kind of vitality that I wasn’t feeling so much the rest of the time. I wasn’t needing to conform.

“And maybe that’s the thing: I didn’t have to code-switch,” she continues. “I could be my strange, mix-y self with my cousins, you know? There was this space for me to just be—and not explain who I am, or where I’m from, or why I look exotic, or these other bizarro fetish-y things that consistently come at me still to this day.”

Line dancing is at the heart of The Brutal Joy, thanks in large part to Chambers’s Chicago-founded memories of folks practising the electric slide everywhere from big weddings to bowling-alley basements. As her relationship to all that source material continues evolving, so does the piece, which is primarily improvised. She draws on an archive of familiar postures and articulations throughout the slow-burning, rhythmic work.

Sound designer and composer Mauricio Pauly is highlighting the key structural elements of Black vernacular music—the vamp, riff, and break—with a live-improvised score. Working closely with lighting designer James Proudfoot, they’re simulating the atmosphere of a basement jazz bar that a young Chambers would visit with her grandmother on Saturday afternoons in Chicago; think cigarette smoke curling through dim lighting, highball glasses clinking against a bartop, and horn players slinging jazz standards with the sort of organized chaos that can only come from years of experience. In all, she recalls, it was sublime.

The Brutal Joy gets its title from a statement by Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña. When Chambers had a conversation with her at the Toronto Biennial of Art a couple of years ago, and admitted that sometimes things feel so beautiful she could die, Vicuña replied knowingly: “The brutal joy.”

Chambers sums it all up pretty succinctly: “If I didn’t have that feeling of the brutal joy, I would die—there would be nothing left of me, you know? And the brutal joy makes me feel like I’m gonna die!”

The dance artist moves through all those feelings in the piece, from devastation to power to confidence. And though her grandmother passed away in 2024 at age 95, Chambers continues to take pride in all the lessons she taught her—not just about fashion, but about accepting love and living boldly. So it’s only fitting that this new work is an ode to some of the most cherished aspects of Black existence.

“The Brutal Joy isn’t about being racialized and denied as a human,” Chambers says. “It is the exact opposite. It’s this ability that somehow—and I think I received this from my Black matrilineal line, I received this from my mother, my grandmother, my great-grandmother, my aunties, and back and back and back—despite, in spite of, we have this capacity to build beauty, nurture beauty, find vitality and life force. It is a beauty that is so intense it’s brutal.

“You know,” she reflects, “I’ve had a couple interviews where they’re like, ‘So, the brutality of being Black.’ I’m like, ‘No, man, the brutality of things being too beautiful!’ Because it’s just overwhelming. I feel like my cells can’t hold it—but of course they can. But because I’m so dramatic, I love the feeling of them not being able to hold it, or feeling like I’m at some sort of capacity for goodness. If only I could always hold that in my life.” ![]()