In Silk Strings, musical cultures fuse through deep history of imperial courts and ancient poetry

Early Music Vancouver Summer Festival and the Sound of Dragon Society join forces to play on Chinese-European musical exchange that is centuries old

Christina Hutten.

Dorothy Chang.

Early Music Vancouver Summer Festival presents Silk Strings: A Chinese-Baroque Musical Dialogue at Christ Church Cathedral on July 29 at 7:30 pm

THERE IS A RECORD, of sorts: a few sheets of manuscript paper, held in the National Library of China, on which the Catholic missionary Teodorico Pedrini has jotted down a dozen violin sonatas. And we also know the bare bones of Pedrini’s life: born to a well-to-do family in Fermo, Italy, in 1671, he was inducted into the clergy at 16 and after an illustrious academic career was dispatched as a papal emissary to the court of the Kangxi Emperor in 1702.

The journey—by way of France, Peru, Mexico, the Philippines, and Macau—took nine years.

Pedrini must have been a skilled diplomat, who seemed to have less trouble negotiating the intricacies of the Qing court than the Byzantine intrigues of the Catholic Church. (His Jesuit rivals had the Vincentian monk imprisoned for two years in the 1720s.) The Chinese aristocracy was also impressed with his musical abilities: he was soon called to maintain and enlarge the court’s collection of Western instruments, taught music to the Imperial children, and even played harpsichord duets, on occasion, with Kangxi himself.

But how did this music actually sound? In keeping with baroque practice, Pedrini’s Dodici Sonate a Violino Solo col Basso del Nepridi—Opera Terza is more of a sketch than a set of detailed instructions. Performers were expected to be able to improvise on the written notes, adding flourishes and diversions of their own. Did Pedrini ape his apparent inspiration, Arcangelo Corelli? Or did he venture further afield and, diplomatically, reference the sound of the Chinese erhu when he turned from the harpsichord to the violin?

We’ll never know. But co-organizer and harpsichordist Christina Hutten promises that such conjectures are at the heart of Silk Strings: A Chinese-Baroque Musical Dialogue, which Early Music Vancouver and the Sound of Dragon Society will present at Christ Church Cathedral on July 29, as part of EMV’s annual summer festival. “You enter very quickly into the realm of speculation,” she enthuses, “and it’s kind of fun to be in that realm and think about what might have happened.

“It’s also sort of fun to be in that realm in the present day and think ‘Okay, what’s possible for us now?’” she adds.

The starting point was obvious: composer and conductor Edward Top’s Farewell Songs, an “alternate history” of Chinese-European musical exchange inspired in part by the Tang dynasty poets Meng Haoran and Wang Wei. Who, as it happens, were also posthumous contributors to Gustav Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde. The multilingual Top has provided his own new translations of those texts, which here will be sung by soprano Emma Parkinson.

“The poetry is part of the core idea of the piece,” says Hutten, “and then he plays with the timbral similarities between Western baroque instruments and Chinese traditional instruments. In that way, he kind of brings them together into a cohesive ensemble, and there’s lots of what we could call musical dialogue going on between the different instruments. Even the way he set it up in the score, you can see the two ensembles, and how they are talking to each other. He’s done a lot of work with [erhu virtuoso and composer] Lan Tung and the Sound of Dragon Ensemble already, so this kind of idea is by no means new to him.”

Further poetic journeys will be explored by composer Dorothy Chang, but instead of working with ancient texts in That Bare Light, she’s chosen to set the words of living Canadian writers: Miriam Dunn, Jan Zwicky, and Eleonore Schönmaier. Not coincidentally, all of them admire the concision and sensitivity to the natural world of their Zen and Taoist precursors.

“All three kind of use natural images to talk about love and loss and the emotions around those things,” Hutten explains. “They use the natural images to get at those emotions without using the emotional words that we often use to describe them, if you know what I mean. The three poems are each really exquisite, and then of course for Dorothy the intermingling of Chinese traditional music and Western styles is sort of basic to her compositional practice, as it is sort of basic to who she is.”

Pedrini's Sonata in G minor will follow, interspersed with passages from his baroque contemporaries Corelli and Matthew Dubourg, before the program concludes with two pieces from Sound of Dragon artistic director Tung, including the work that gave her company its name.

“From the perspective of a player of Western early music, the language strikes me very much as contemporary to our present day, but she uses a lot of musical elements that are familiar to us,” Hutten says. “For example, in that final piece she sort of sets it up, initially, with a traditional song. but then it starts to deviate a little bit. There are some Moroccan rhythms that undergird the piece, and then she gives members of the ensemble opportunities to improvise on their instruments. So those sections will be different every time we do it, and reflective of the unique abilities of whoever is the soloist, and the musical language that comes naturally to them.”

This will be a stretch for everyone in the ensemble, Hutten concedes. (Also appearing will be Tung and Jun Rong on erhu; Zhongxi Wu playing suona and sheng; Dailin Hsieh on zheng; percussionist Gregory Samek; violinist Majka Demcak; cellist Martin Krátký; Jesse Lu on bass; and Jeremy Berkman on sackbut.) But in general, she adds, there are more similarities than differences between Chinese music and its baroque counterpart.

“On the most basic level, there’s the way that both practices are so rooted in song,” she begins. “That’s also kind of the germ around which the program developed: the idea that you might have a traditional song that is even thousands of years old and over those thousands of years it’s become a very fruitful seed for a lot of very different compositions and improvisations and that sort of thing. So that’s one element. I would say they also share a basic approach to music that involves decoration or ornamentation, often improvised ornamentation. You might start with a simple idea, sometimes a very old simple idea, and the way that you develop it is by making it more and more beautiful, the way that you might develop a piece of furniture by adding beautiful carving, or painting it beautifully. I think both styles really share that sort of notion.”

Once those commonalities are observed, Hutten’s “broader hope” is that other cultural boundaries can be more easily bridged.

“This is an interesting moment to create art,” she says, “and we hope that it might actually inspire everyone—the musicians and also the people who are listening—to just think about the places of connection within our very diverse neighbourhoods in Vancouver, and inspire ways in which we might reach out to one another, and learn about each other, and make beautiful things together.” ![]()

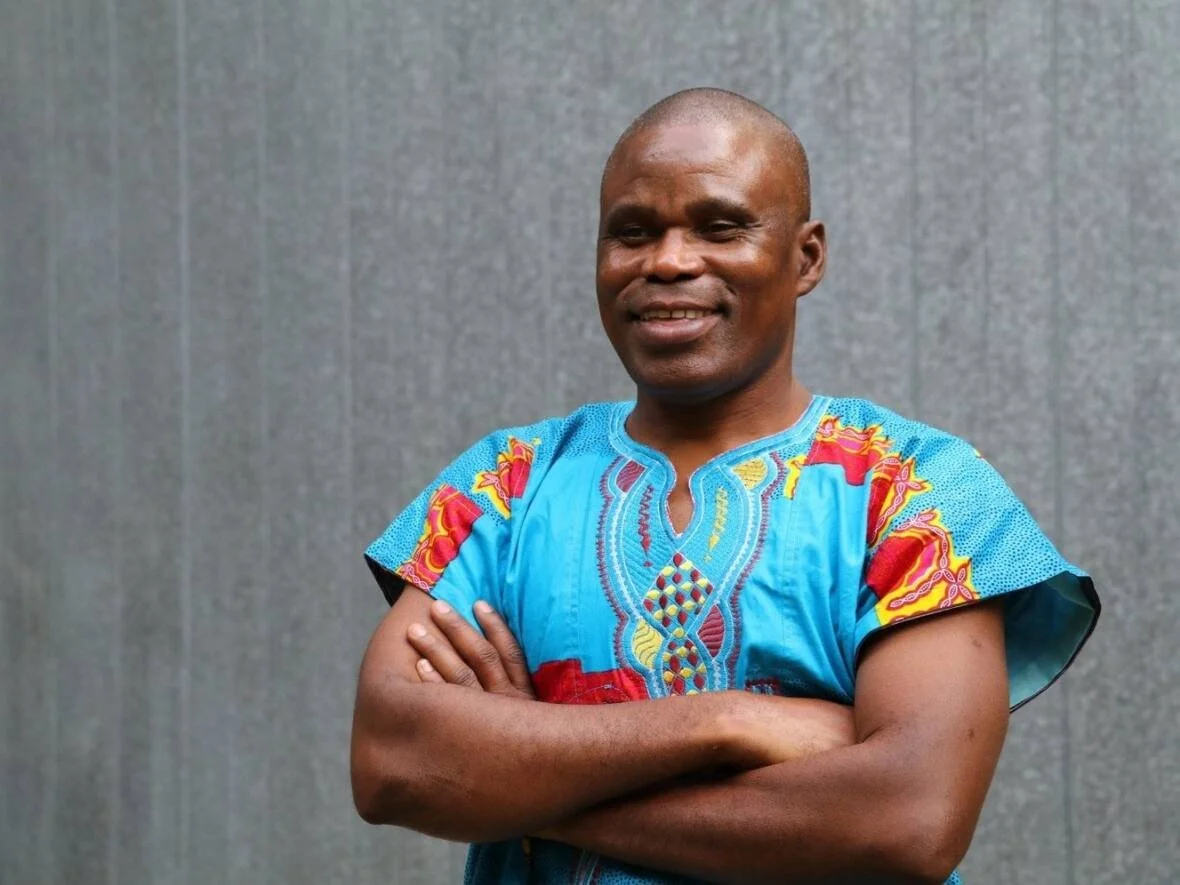

Lan Tung. Photo by Nenad Stevanovic