Onibana Taiko pumps Japanese tradition full of riot grrrl aesthetics at the Powell Street Festival

Taiko artists Noriko Kobayashi and E. Kage reflect on punk-rock roots and gender expression

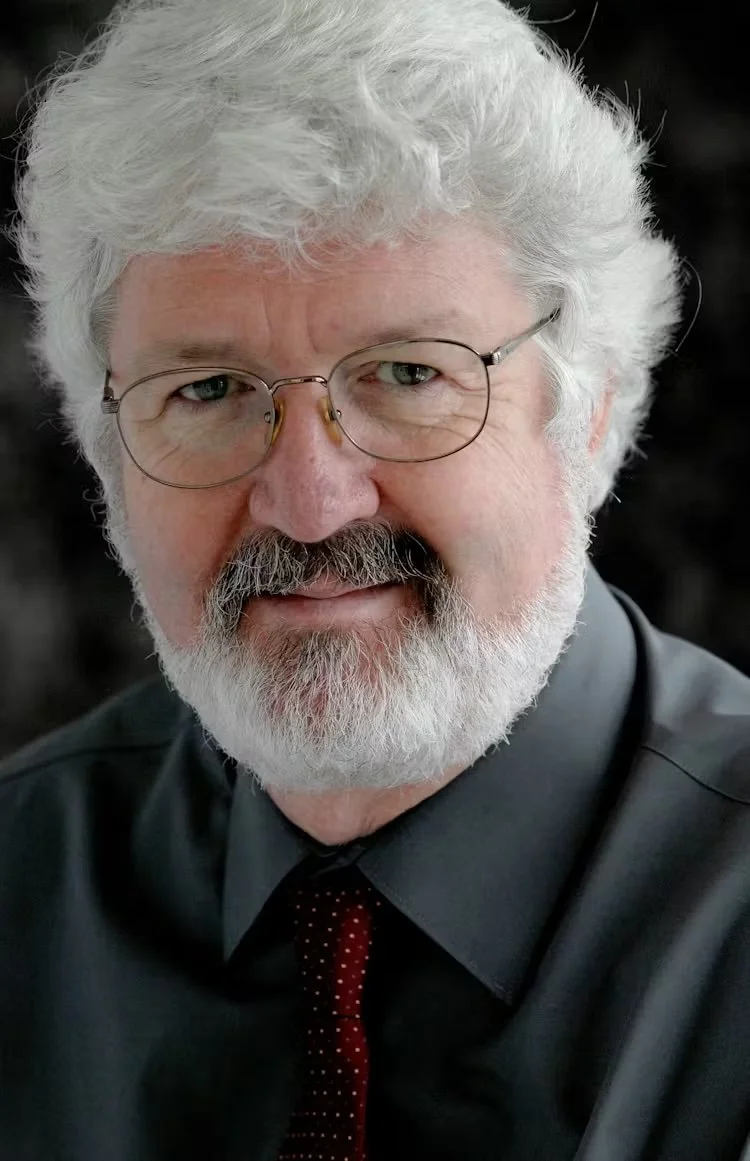

Onibana Taiko performing at the Powell Street Festival. Photo by Fatima Jaffer

As part of the Powell Street Festival, Onibana Taiko plays on the Street Stage at Jackson Avenue and Alexander Street on August 2 at 2:30 pm

THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT, a feminist offshoot of punk subculture that gained traction in the ’90s, has more in common with Japanese taiko than first meets the eye.

To unpack why, let’s dive into the history of Onibana Taiko, a Vancouver-based group that’s playing at this year’s Powell Street Festival, on August 2. Cofounders Noriko Kobayashi, E. Kage, and Leslie Komori (who won’t be with the group on this occasion) inject punk aesthetics and sound into traditional Japanese elements like obon, an ancestral communication ceremony grounded in taiko rhythms, and oharai, a purification ritual that involves dancing with folding fans.

Montreal-born musician Kobayashi comes from a background as a bassist in the San Francisco queercore band Tribe 8, with which she toured the U.S. and Europe in the early ’90s, using the aliases Mahia and Mahoo. Fans worshipped the group for its iconoclastic punk lyrics and hardcore performances; lead singer Lynn Breedlove, for instance, often took to the stage shirtless while wearing a strap-on dildo.

Kobayashi eventually left Tribe 8 because of creative frustrations, and—fuelled by a desire to be surrounded by other Asian women—moved to Vancouver. Speaking to Stir by Zoom alongside Kage, Kobayashi reflects on how returning to Canada allowed her to reconnect with her heritage.

“I spent quite a bit of time being angry, and being a punk rocker, and trying to change the world and everything,” she says. “I was far away from my Japanese culture. I was in a very sort of Caucasian punk-rock world. We were all disaffected, so that’s what brought us together. But I was so far. I wasn’t eating the food anymore.

“I think in the end,” she continues, “I wanted to return to my Japanese culture when I came back—and the home that Japanese Canadian communities offer. That was my big thing, you know? I was changing the kind of music I was making, but this was really different. It was really wonderful to be back in the warm embrace of the Japanese Canadian community and culture.”

Kobayashi grew up surrounded by Nikkei culture. Her parents were involved in the Montreal Japanese Canadian association and spoke the language at home. She moved to London as a young adult, immersing herself in the punk-rock scene for five years before heading to San Francisco to play with Tribe 8. It wasn’t until she came to Vancouver in her 30s that she met Komori, who was a member of Sawagi Taiko at the time, and was introduced to the art form.

What Kobayashi found in taiko was a new way to channel her anger and express her identity.

“Feminists were gravitating to taiko as a form of empowerment,” Kobayashi notes, “and it was there that I met a lot of the more radical feminists in the queer and lesbian community. And that is similar to what was going on with the riot grrrls during the ’90s. It’s about creating a space for women to be strong, to be powerful, to not let the boys push us around; have our own space, our own mosh pit, our own culture.”

Kobayashi soon left for Japan, and spent eight years there studying the art form more closely before cofounding Onibana Taiko. She also plays shamisen, a three-stringed Japanese instrument that can sound nearly as powerful as a beaten drum, depending on how it’s plucked.

Onibana Taiko. Photo by Toonasa Photography

Kage, who identifies as gender nonbinary, brings another perspective to taiko. Having grown up in Japan studying martial arts during the ’60s and ’70s, they emigrated to Canada at age nine, and were shocked by the difference between traditional taiko—a stringent, predominantly male art form—and its more inclusive North American counterpart. Kage began playing in their teens, taking workshops and starting their own groups, later touring around the U.S. and Europe.

“There were women playing—all kinds of people, mixed-race people,” they say of first seeing the drummers in action in Vancouver at the Powell Street Festival. “People were actually smiling, jumping around, and having a good time. So I felt for the first time, I could do that.”

Another important aspect of Onibana Taiko’s style, says the artist, is defying convention. For instance, Kage and Kobayashi draw on elements of the classical Japanese theatre form kabuki—in which men have historically performed all the women’s roles—and give it a full genderfuck makeover with masks and costumes.

“While training with other mostly Asian North Americans, it was like I felt freer to explore myself or express myself through taiko,” Kage explains. “And I would say I was an angry young woman, so taiko was an outlet…. Many of us were attracted to taiko because it was a way to be powerful onstage and smash the negative stereotypes of particularly Asian women being subservient and demure.”

Kage notes that they’re grateful for the Powell Street Festival’s acceptance of nontraditional artist groups like Onibana Taiko. Even the trio’s name is outside the box—onibana is a type of flower, but it closely resembles the Japanese word onibaba, which means “mountain hag”.

“Some of the more traditional parents, like Noriko’s, were horrified that our name was very close to onibaba—right, Nori?” Kage says, and Kobayashi nods and laughs. “But we liked it. You know how the word queer was derogatory, and now we call ourselves queer? It’s a little bit like that.”

Kobayashi in particular notes that she connects to reclaiming the concept of a crone or hag. “In London,” she recalls, “I was hanging around the Greenham Common Women. And because everyone was kind of wicca and kind of pagan, there was an embrace of the crone. So, during my time with active feminism, there was always this sort of embrace of the crone. That was in England, and then when I was in San Francisco, we had a fan group called the SF Hags. So again, there’s an embrace of the crone.

“Radical feminism is also about reclaiming the hag,” she continues, “because they say as you get older as women, you’re just useless—you can’t bear kids, and you’re whatever, you know, you’re reduced to the background. I think a lot of that old-school feminism was really into embracing and empowering the crone, because actually as women, you’re more empowered as you get older.”

Kage and Kobayashi aren’t slowing down their work with Onibana Taiko anytime soon. At the Powell Street Festival, they’ll be collaborating with L.A.–based taiko group Mujō Dream Flight—which is predominantly composed of trans and nonbinary artists—on a traditional obon song. Cynthia Dawn, who was a member of the defunct Oakland band La Fin Absolute du Monde, will join the duo for a few punk-rock songs (including a reimagined Tribe 8 track). And Onibana Taiko will also perform Reverberation, a recent commission by the Vancouver Taiko Society, with support from the Japanese Canadian Legacies Fund. The 12-minute concept piece is about resilience in the aftermath of the Japanese Canadian internment.

“Part of working on Reverberation was that taiko is a way for us to communicate with our ancestors,” Kage says. “And we are also going to be ancestors. That’s inevitable someday. It’s forging that connection, so maybe taiko would be a way to connect with the present world once we are ancestors. As we get older, I feel like there’s more and more awareness about that, you know? We’re not going to be around forever.”

That may be true—but the pair’s impact on the taiko scene here will surely live on. ![]()