At grunt gallery, Jenie Gao transforms paper, wood, and familial lore into reimagined keepsakes

In Where Mountain Cats Live exhibit, Kansas-raised printmaker and installation artist illuminates Taiwanese-Chinese American experience through everything from a “lazy Susan” to jade pendant prints

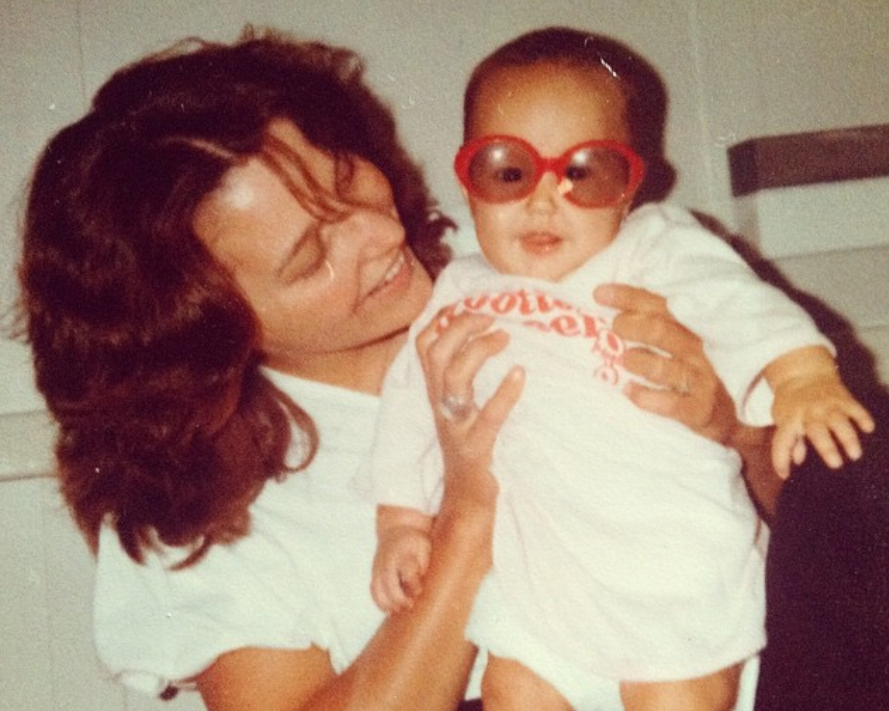

Jenie Gao with their artwork Cycle | Breaking and Making from “The Negotiation Table” series. Photo by Khim Hipol

grunt gallery presents Where Mountain Cats Live to January 17, 2026

AS ATTENDEES WALK THROUGH Jenie Gao’s latest solo exhibition, Where Mountain Cats Live, grunt gallery’s adjacent space gradually overflows in anticipation of the artist’s opening-night talk. Teary eyes can be seen in response to the prints, artist’s books, and table-based installation, all of which Gao describes as a “love letter” to their Taiwanese mother and extended communities. As Gao begins speaking on their process and philosophy, they glide through the projected slides behind them, showing images and concept sketches of their work.

“The arts industry is partially designed to rely on unpaid artists’ labour, which is then further weaponized to gentrify cities,” says Gao. “The marginalized artist must contend with a two-fold problem. There is a dire need for our work to exist, and the systems around us readily prey upon what we create. So I enter my work with the question ‘Whom will this work benefit?’”

In Where Mountain Cats Live, Gao transforms paper, wood, and familial lore into reimagined pieces of autobiographical and political keepsakes. The centrepiece of the exhibition uses the classic “lazy Susan” design—a post-colonial innovation synonymous with Chinese restaurant culture across the diaspora—slowly rotating a wood-block carving of a homing pigeon opposite a fenghuang, the mythical Chinese phoenix. The homing pigeon pays homage to Gao’s father, who resorted to raising them during the Cultural Revolution, as well as Gao’s childhood memories of looking after retired or discarded pigeons with him once he emigrated to the U.S.

During their travels between the U.S. and Canada for work and caregiving, Gao has recorded about 30,000 words of their mother’s stories, and describes her as a “family knowledge-keeper”, a role that Gao has naturally inherited as a historian and artist. Glimpses of these stories can be found in each object, including the letterpress book Yuǎn Yuàn, which chronicles three generations of their family’s history. Nestled in intricately folded three-dimensional paper art and non-linear, multi-directional text lie stories of quiet struggle and deep perseverance under colonial systems. Yuǎn Yuàn, alongside Gao’s “lazy Susan” installation, is part of their ongoing series “The Negotiation Table”, which explores the cultural and political intersections of these shared spaces.

“The table is a gathering space imbued with social and political significance,” Gao says. “It contains the promise of inclusion and decision-making contingent upon an invitation, and the invitation suggests that power is conditional, and that just as it can be granted, it can be taken away.”

Coloured prints of the transformed wood carving are framed near the table, bringing forth Gao’s exploration of material culture and waste. For “The Negotiation Table” series, hand-carved wood blocks are transformed and repurposed after the prints are made, disrupting the traditional narrative around material value. This process can be also seen in Gao’s Cycle | Breaking and Making, where they reclaim the Chippendale table, a design dating back to the Ming dynasty but renamed after British furniture maker Thomas Chippendale, who popularized it in the West.

“Historically, printmaking has played a crucial role in community organizing,” Gao explains. “It’s often regarded as the first [form of] mass communication, an analogue way to distribute messages to the masses. But in its assimilation into the fine arts, printmaking adopted best practices that included the destruction of the printing plate to limit the editions of the prints. I’ve always been uncomfortable with this practice of destroying evidence of a labour to rarefy the asset and thereby prove that if it is rare, it is valuable.”

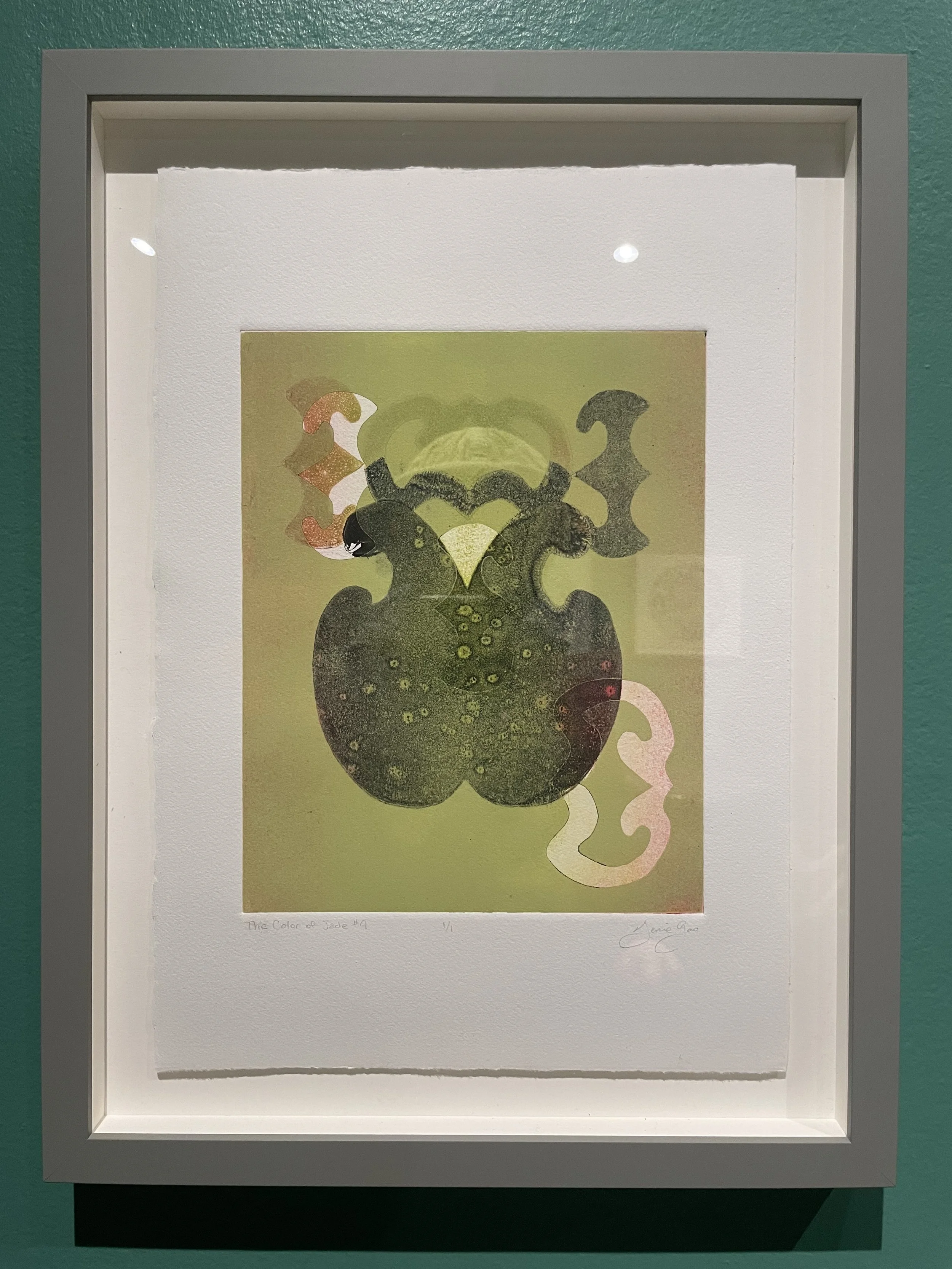

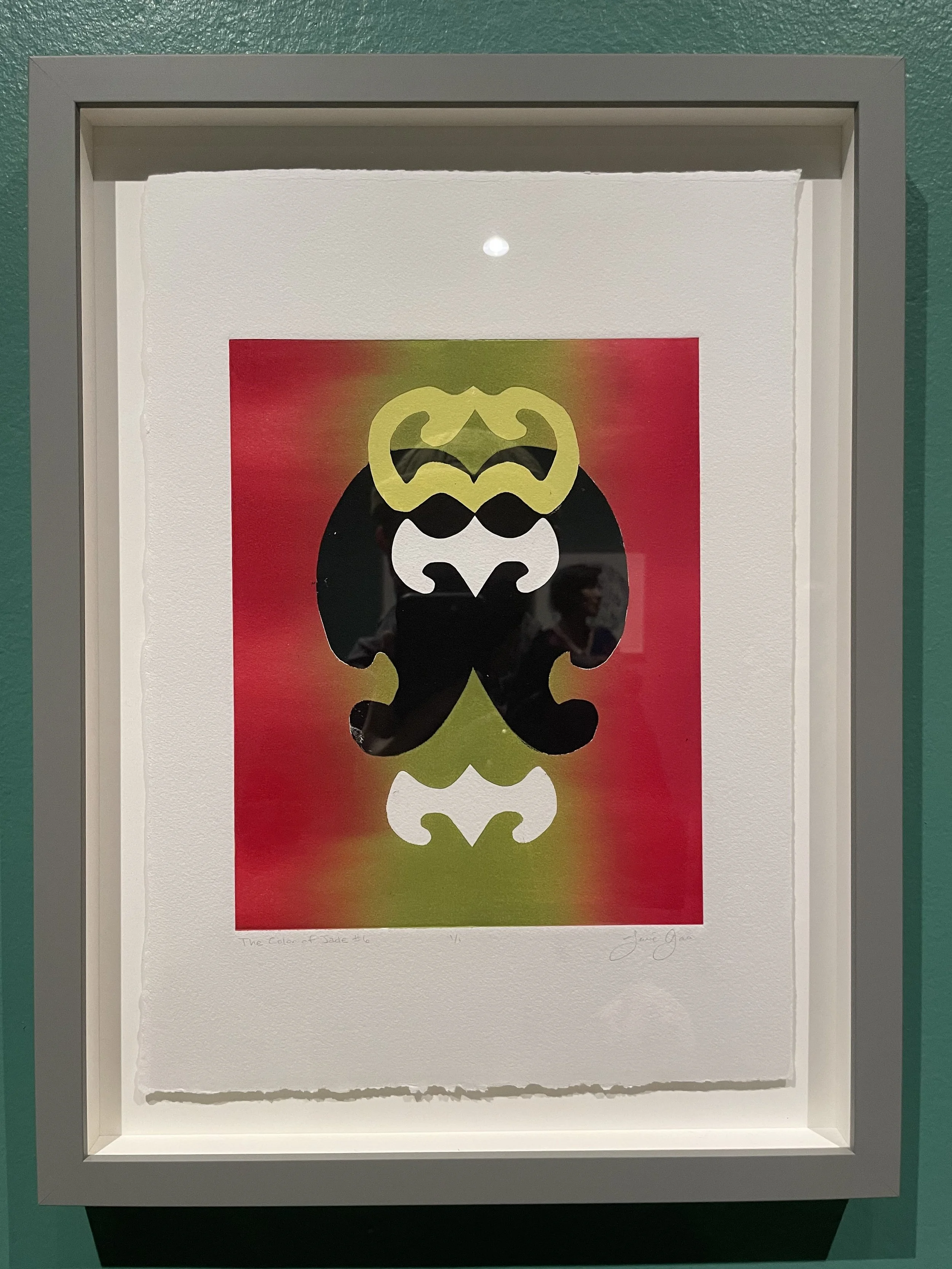

Prints from Jenie Gao’s The Color of Jade: After Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Forbidden Colors. Photos by Robert Kuang

The immigrant and diasporic stories represented in Where Mountain Cats Live are anything but rare and, fortunately, are increasingly visible in the world of fine art. They form the foundation of Guiding Ethos, an exhibition featuring Gao as guest curator at the Trout Museum of Art in Appleton, Wisconsin, showing 25 North American artists whose practices use storytelling as record and resistance. They also resonate with other notable grunt exhibitions, such as Sue Dong Eng and Mercedes Eng’s 2024 show Inside/Out: the art show my dad never had. What sets Where Mountain Cats Live apart is perhaps best captured in Gao’s ethos of artistic practice as a form of direct action, where their community-organizing experience informs the work just as much as their background in printmaking.

The exhibition title connects chapters in Gao’s family history. It is inspired by a story told by Gao’s mother, in which she recalls bravely confronting “mountain lions” outside her mountainside childhood home in Keelung, Taiwan. At the same time, the title alludes to the local flora and fauna surrounding Gao’s mother’s home in rural Kansas, an environment increasingly threatened by ecological destruction. This diasporic intersection is echoed in The Color of Jade: After Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Forbidden Colors, which includes four prints featuring a jade pendant gifted to Gao by their mother, while their colours invoke the late Cuban-American artist’s exploration of the Palestinian flag as a symbol of resistance.

As noted in exhibition curator Katrina Orlowski’s introduction, grunt’s definition of expertise includes bringing your whole self to the space. For Gao, this means a merging of the personal and political. The mounting housing-affordability crisis in Canada and the U.S. is acknowledged in Gao’s talk, through their mother’s stories, and through Orlowski’s words.

“Though Gao has not always lived here, having spent much of their life in the U.S., in both their artwork and otherwise, they demonstrate a deep attentiveness to how forces that have shaped this place are undeniably connected to the very same forces that have shaped their own life, their family’s history, and their creative practice,” Orlowski writes. “How colonial powers across lands and waters have uprooted and disconnected so many—and continue to do so here, in Taiwan, China, the U.S., Palestine and elsewhere.”

Following the debut of new works this year in Calgary and Vancouver, Gao’s exhibition works will travel throughout the U.S. next year, beginning at the Pratt Munson Gallery at the Munson Museum of Art in upstate New York in February. As a steward of community storytelling, Gao invites people to think about storytelling through the lens of responsibility and compassion.

“The goal of this is not to just create content that colonial systems can weaponize and pit one group against another, like what we’re seeing happen with Israel and Palestine, the weaponization of Jewish trauma and the damage that that’s doing, and the resulting genocide against Palestinians,” says Gao. “How do our stories make us more capable of being in community with one another in a way that is both accountable and compassionate?” ![]()