Stir Q&A: With Cicadas, filmmaker Luna Marán reflects collective vision that shapes Oaxaca life

Through its mix of Indigenous artists, musicians, and technicians, the Vancouver Latin American Film Festival feature puts the common good at the centre

Cicadas.

The Vancouver Latin American Film Festival presents Cicadas at The Cinematheque on September 6 at 2 pm

HIGH IN THE Sierra Juárez of Oaxaca—mountains named after Benito Juárez, Mexico’s first Indigenous president, born in nearby Guelatao—filmmaker Luna Marán sets San Pablo Begú, a fictional town that feels close to her own. One night, heavy machinery trucks cut through the dark but are stopped by neighbours on watch. It’s the first sign of a highway project the community hasn’t approved yet. From there begin the whispers, the long nights of debate, and the complex work of deciding a collective future.

The opening credits of Cicadas, Marán’s first narrative feature, say it plainly: “a film made by”. Her name appears among 30 or so others.

The film speaks through many textures and many voices: a bureaucrat in endless paperwork, a boy recording daily life with a cellphone, a woman pressing local leaders for action, elders debating the future, teenagers dreaming of leaving. The result holds close to the smallest details but opens wide in its vision. It’s encompassing, tender, and incisive.

Its collective spirit also reflects Marán’s own trajectory as a filmmaker. We began our conversation there, before turning to the making of Cicadas.

You left Oaxaca to study film, but eventually came back to make work in your own community of Guelatao. What brought you back?

My first experience with filmmaking was playful and exploratory, part of an experimental workshop with Bruno Varela and Isabel Rojas called Mirada Biónica.

Later I studied film in Guadalajara and what I encountered there was much more traditional and industry-driven. I clashed with it, because cinema, like many industries under capitalism, is built on exploitation. I saw what we’ve all heard about: neurotic directors, producers pushing people to work endless hours, sometimes without food. Practices that would be unacceptable elsewhere, but in film are still tolerated.

Where I grew up, the normal thing was to hold an assembly, decide together, and then get to work. So when I found myself in spaces with no dialogue, where the producer was the ultimate authority, I shut down.

That’s why I returned, first to Oaxaca City, then to my hometown. I knew I loved making films, but not in the ways I was being told. Back home, with colleagues, we began running workshops and imagining other ways of working. Over time we moved into making feature films, putting the theory into practice. Eventually, I realized there are filmmakers everywhere trying to do things differently, each in their own way, pushing back against the industry’s violent logic.

You’ve said comunalidad—this Zapotec way of life rooted in shared labour, community governance, and celebration—runs through your upbringing. How does it connect to the way you make films?

Comunalidad is a word that came about in the 1980s to describe an organizational process and a way of life in southern Mexico—though in reality, it’s much older. It gave a name to a way of living that puts the common good at the centre.

Making films from comunalidad means cinema that speaks with that way of life, stories that can be of real use to the people who live it. I like to think of it in contrast to commercial cinema, whose purpose is essentially to generate profit. Communal or collective cinema, instead, insists that the stories we tell serve the community. And not in a didactic way, but as a kind of provocation from within.

How does that perspective come through in your film Cicadas?

Cicadas reflects how a community organizes itself, the complexity of making decisions in assembly. And it also asks: How much are we really listening to the new generations? How much are they being taken into account as we imagine the future?

The film is collective at heart, though I understand it began with a single protagonist. How did it grow into a chorus of voices?

The script kept evolving because, among other things, I had to do community service in the town where I live, and that forced me to look at the story differently. I took on the role of topil—these are the young people who, in the film, are seen doing tasks like delivering water and keeping watch. From that experience I felt the need to include more characters and add complexity to the story.

How did the process of creating in community shape the way the film was made?

To make the film possible, we had to be very mindful of people’s time. It sounds obvious, but it’s about understanding the place a film has in daily life: it isn’t the main event, it’s secondary. We had to organize things in a way that let people participate without neglecting their other responsibilities, because life in community is already demanding.

Another thing was our decision to work only with Zapotec, Mixtec, and Triqui technicians, artists, musicians, and performers. In an industry that makes it so difficult for people from Indigenous communities to participate, we wanted to prove that a film could be made entirely by artists from these cultures. The advantage was also the shared understanding. There was less to explain, because so much was already clear to everyone; we come from the same way of life.

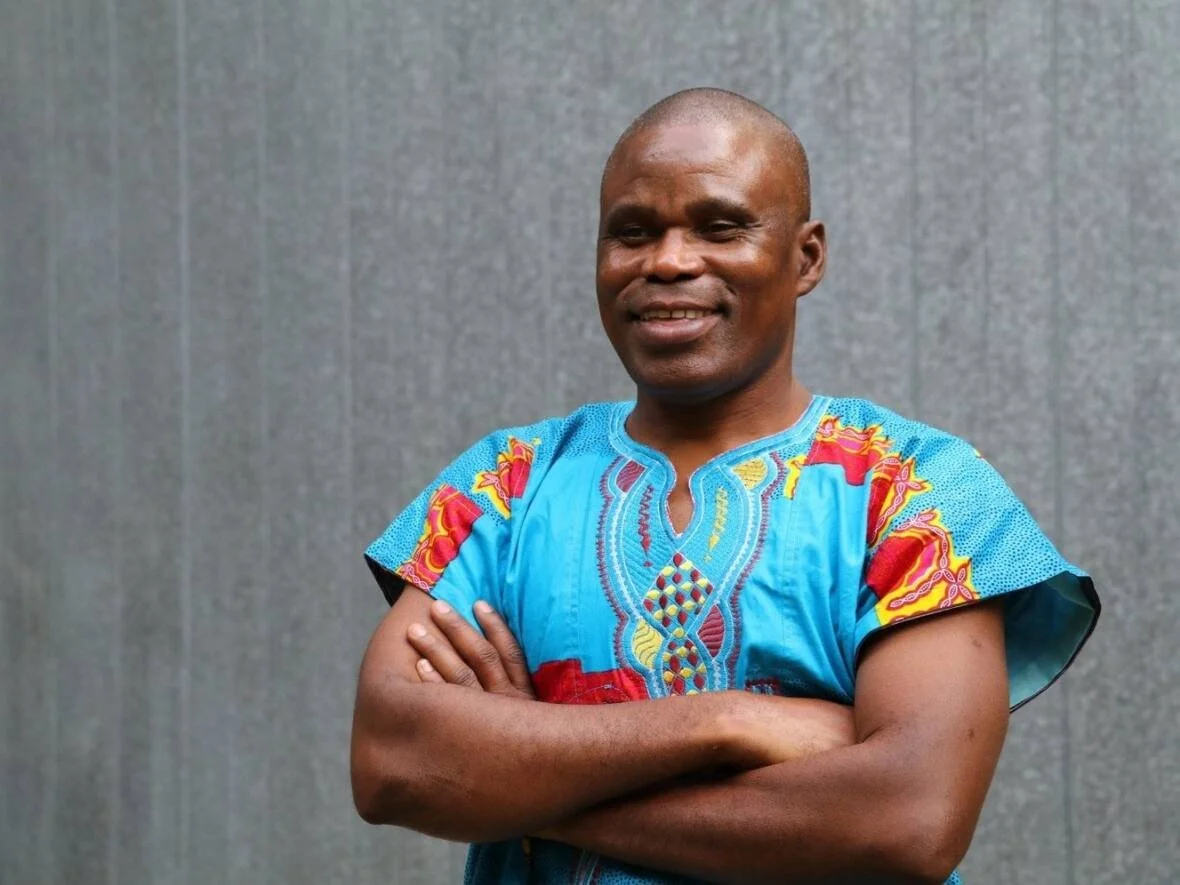

Luna Marán

Music is such a vital part of the film. How did you approach it?

We set ourselves a rule: only music from the region. You’ll hear philharmonic band music, mostly contemporary and original, including the main theme by Ayuujk composer Eduardo Díaz Méndez. We also drew on recent regional hits, thanks to our closeness with local musicians. And for the bohemian night scene, we reinterpreted two songs by my father, Jaime Martínez Luna, a composer and philosopher I portrayed in my earlier documentary film Tío Yim.

It was all part of the same commitment: to work with and highlight the richness of the region’s musicians—of which the film can only show a fraction.

The film carries a serious central conflict, but there’s also so much lightness, music, and laughter.

Something we don’t explain in the film, but that’s important to mention, is that community service roles—from president to council member to topil—are all unpaid. You’re chosen and then serve for a year, a year and a half, sometimes two, with no pay at all. And within the weight of that responsibility, humour and fun is what allows people to keep going.

In wanting the film to carry that weight of reality, we wanted to show the way it actually is: you move from a very formal, very serious situation straight into laughter among neighbours.

In the film we see women’s roles in community service through characters like Yuli, a young teacher and topil, and the town treasurer who's also a mother. What did you want to highlight with these characters?

It was meant as an homage, because the effort these women make is immense. Community service adds another burden when household and caregiving work already falls mostly on them. So when women also take on those roles, they truly become heroines.

Seeing them onscreen in the role of, for example, topiles is also significant because in many communities those tasks are reserved for men. It feels important, both as testimony for future generations and as a way to spark complex conversations in places where it still doesn’t happen.

What was it like to show the film to the people who were involved in making it?

During editing I shared the film with the main actors, not to appease them—many aren’t actors by profession—but because they carry the knowledge that makes the fiction ring true. That dialogue mattered to me.

I showed the film in different stages, and by the end, it was deeply moving. One woman from my town said, “That’s us, Lunita.” That affirmation that the film truly reflects the community meant so much to me.

How does it feel for Cicadas to now speak to audiences at the Vancouver Latin American Film Festival?

I’m deeply touched that Cicadas will be alongside other films by Indigenous filmmakers, because together they remind us of the many different ways there are to live on this planet.

For me, that’s the essence of cinema: a window into other worlds. I hope people can look through this one and say, “In that part of Oaxaca, life is lived this way.” That’s what we want—to share who we are, the questions we carry, the conflicts that shape us—with the hope that other films will open windows back, onto other corners of the world.

![]()