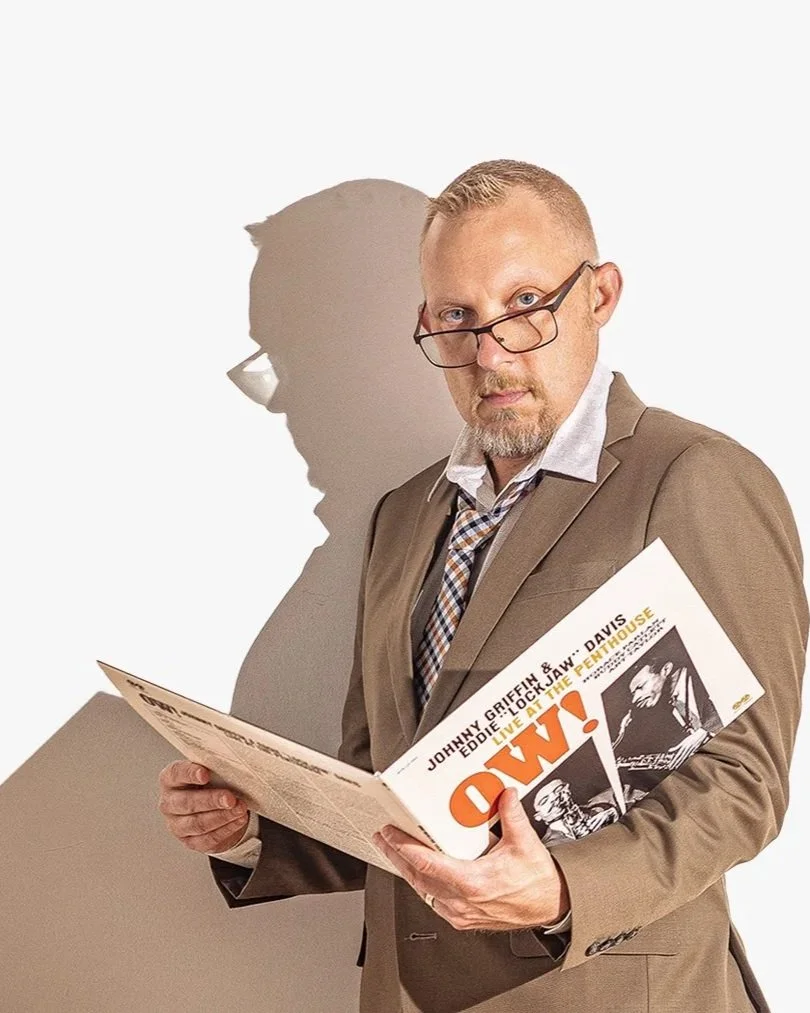

Saxophonist Cory Weeds champions local jazz scene, improvising across record labels, clubs, and fests

The performer and self-taught entrepreneur has fearlessly forged his own path, not only onstage but with Frankie’s Jazz Club, the thriving Cellar label, Jazz at the Bolt, and more

Cory Weeds

HOW DID CORY WEEDS become one of the best things that’s ever happened to mainstream jazz in Vancouver? It’s simple. “I always liked reward,” says the saxophonist and entrepreneur, reached during some rare downtime following an out-of-town gig with veteran guitarist Peter Bernstein.

“I was never the kind of guy where I’d say, ‘Okay, you’re going to make this much money, and it’s going to be this much every month, and you’re going to be comfortable,’” he continues. “I’m more like ‘I’d like to make more. How can I make more?’ And I could take a risk. I wouldn’t say the risk never stressed me out; I was just never really scared of money. I was just like ‘Oh, if it’s money stopping me from doing what I’d like to be doing, then let’s make it work.’ And I like the reward, but in some ways the entrepreneurship was less about the money and more about ‘I just want to have control. I want to create it, and I want to oversee it, and I want to make the decisions, and I want to have my name on it.’”

Just where this fearless attitude comes from remains a mystery. Entrepreneurship, he notes, is not necessarily in his genes. Music, however, might have been.

“Music was just always in my house,” says Weeds, whose father, jazz guitarist Bill Weeds, is a recording artist in his own right. “I played piano and did the conservatory thing, but I was never interested in that per se. And I took some [saxophone] lessons. I had a cousin who lives in Port Alberni, of all places, who was kind of a hero of mine. He played saxophone, and he was two years older than me; I just thought he was the coolest guy ever.

“So the interest started to pick up in high school, and then it really picked up. I was listening to all the stuff my dad was playing, and I kind of clicked with a Wes Montgomery recording that my dad was playing a lot. That was the ‘aha’ moment, when I was like, ‘Oh, yeah, I get this music now, and I want to do this music.’”

Serendipity kicked in. Weeds was playing baseball at his sports-heavy high school, and his coach just happened to be a band teacher at a different institution. The switch was made, which led to a stint at what was then Capilano College, and from there to the prestigious jazz program at the University of North Texas. Private lessons with the Swiss sax virtuoso George Robert—then married to a Canadian and living in Vancouver—didn’t hurt.

“We became very close, and he was really influential,” Weeds says. “I tried to do everything like him, including playing, of course, but I also tried to dress like him, I tried to stand like him, I tried to hold my saxophone like him. I mean, he was a real, real hero of mine.”

In time, Weeds felt ready to make the leap that so many other Canadian musicians had made before him: pack up the horn and some sharp suits and move to New York City, the jazz capital of the known universe.

Except that he didn’t.

“The realization was not that I didn’t have what it took,” he explains. “But I didn’t really have an interest in practising 10 hours a day, moving to New York, and trying to hustle it. I just didn’t have that kind of dedication. But I knew that I wanted to be close to the music, that I wanted to make my life in the music. And I didn’t want to teach, so there were a whole bunch of things that I knew that I didn’t want. I wasn’t totally sure that I knew what I wanted, except that I wanted to be in this music, and I realized that if you want to be in this music you have to be open to doing different things. And that’s just sort of the way it worked for me.”

So he opened a jazz club, the Cellar. And when that folded, he opened another one, Frankie’s (set to host a soldout three-night run of pianist David Hazeltine and trombonist Steve Davis’s new sextet called Primary Influences, debuting new work the group is set to record back in New York City).

He also started a record label—or is it three record labels? (Cellar Live, for live recordings; Cellar Music, for studio projects; and Reel to Real, for archival material featuring jazz stars of the past.) He booked shows for the Vancouver International Jazz Festival, and initiated a yearly mini-festival at the Shadbolt Centre for the Arts, the most prestigious venue in his native Burnaby. (This year’s edition of Jazz at the Bolt will happen on February 14 and 15.) And he began to build on his growing list of international contacts, especially those in the city that he didn’t move to, New York. And the flow has gone both ways: not only is Weeds continuing to host a glittering array of American stars here in Vancouver, he’s creating opportunities both here and abroad for our own homegrown talent.

“I’ve always been an advocate for the level of musicianship here in Vancouver, and how lucky we’ve been,” he says. “We’ve lost some over the years, like Ross Taggart and Chris Nelson and Bob Murphy, but the musicianship has always been very strong here, and it was always a big sense of pride to bring somebody from New York and have them play with local musicians—and not only sound good, but really like it. Like, David ‘Fathead’ Newman made Jodi Proznick, Tilden Webb, and Jesse Cahill his West Coast band for a couple of years. And the last two nights, we played with some young guys and Peter Bernstein, and Peter was just raving about the young guys all the way to the airport this morning: ‘They could play anywhere, and they’re going to be really good musicians.’ So I take a lot of pride when I can bring a guy or a girl here and they have that kind of experience.

“Not every experience has been like that,” he adds. “Some come in and they don’t say much, just do their job, get their money, and go home. But I’ve established great relationships with guys like Bernstein and David Hazeltine and Steve Davis. Mike DiRubbo! We just did a Mike DiRubbo record because he loves the band here.”

The American saxophonist’s second Cellar effort will be added to a catalogue of well over 200 releases, an astounding feat made possible by Weeds’s ability to keep costs low, access diverse funding sources, and offer a fair deal to emerging artists and established stars alike.

“There’s a few ways we do stuff,” he explains. “In one sense, we operate as a full-on, old-school record label, where I will reach out and say, ‘Hey, I’ve been checking you out. Would love for you to make a record for the label. Let’s sign you to a one-record deal.’ And then I pay all the freight and hope like hell I make all my money back. We also have FACTOR funding, so if you’re Canadian, that’s a checked box. If I like the music, that’s a second checked box. If we can work together to make something happen that’s successful, that’s a third checked box. All those models kind of feed off each other, and I like working with younger artists because younger artists are more open to using all these tools that are accessible to them, like social media. And that’s really important these days, like really, really, really important. And I’m trying to find a release that will pay for itself or maybe even make a little money, so that maybe I can do a release with an older artist that I’m passionate about.

“I’m not being very articulate,” he adds. “The label generates a lot of revenue, but it’s not something that I feed my family with. It’s something that sits in the background and generates enough revenue that I can keep putting out records. I have the luxury of having some grants, and the luxury of being able to take a couple of risks. And if they don’t work out, well, they don’t work out and it’s not the end of the world.”

Weeds doesn’t lean too heavily on his own role as a musician, although he leads multiple bands and plays in several more. And somehow he always finds time to practise his horn—if not 10 hours a day, enough to keep improving, no easy task for someone in their early 50s. His approach to the saxophone may be rooted in a well-worn tradition, but he’s increasingly capable of tapping into what the great jazz critic Whitney Balliett once memorably called “the sound of surprise”. (You can hear it yourself when he plays Frankie’s January 7 for Weeds/Wine/Wednesday with a new band featuring Tilden Webb on piano, David Caballero on bass, and Graham Vilette on drums.)

“I don’t have any regrets that I didn’t move to New York,” he says, contemplating his decision not to pursue a full-time life on the stage. “I’ve been able to create what I want to create, and live in the place that I want to live in, and not have to struggle.

“In everything I’ve done in my life, I’ve never listened to anybody who said, ‘Oh, you can’t do that. That’s not possible,’” he continues. “That never entered my mind. I’d be like, ‘What do you mean it’s not possible? Let’s just figure out a way to make it possible.’ So I was really industrious—and I’d call it sort of blind stupidity too. I was too stupid to know any different, or too stupid to listen to anybody and be like, ’You’re right. I shouldn’t do this.’ So I just did it!” ![]()