Daily human cost of the Russo-Ukrainian war revealed in PuSh Fest’s Eight Short Compositions

The starkly moving show by the Czech Republic’s Archa Centre of Documentary Theatre recounts true stories of lives upended by the conflict

Eight Short Compositions on the Lives of Ukrainians for a Western Audience

With Vancouver Poetry House, the PuSh International Performing Arts Festival presents Eight Short Compositions on the Lives of Ukrainians for a Western Audience at the Waterfront Theatre on January 22 and 23 at 8 pm

THE TRUE COST of war isn’t necessarily calculated by adding up the numbers of battlefield casualties or the schools and hospitals lost to missile strikes. It’s tallied in the trauma it can inflict on entire generations of people for whom life can never truly go back to the way it was before.

The full impact of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine may not be evident for some time to come, as the war there continues. As this article is being written, Russian troops occupy almost 20 percent of Ukraine. Hundreds of thousands of military personnel and tens of thousands of civilians have died, and millions of Ukrainians have fled the country, creating the worst refugee crisis Europe has seen since the Second World War.

Produced by the Czech Republic’s Archa Centre of Documentary Theatre, Eight Short Compositions on the Lives of Ukrainians for a Western Audience isn’t about those facts and figures. The show, based on stories collected by playwright Anastasiia Kosodii, is instead about small moments in the daily lives of ordinary Ukrainians as they navigate this most extraordinary time.

Archa’s Jana Svobodová conceived of Eight Short Compositions after she used some of Kosodii’s texts in the International Summer School of Documentary Theatre, which the company hosts each year.

“Later, when the Summer School was over, I realized, ‘Oh my God, we can make a show out of it,’ because it was already working. There was something in it,” Svobodová tells Stir via Zoom from Prague, where she’s joined by her Archa Centre of Documentary Theatre cofounder, Ondřej Hrab.

“It came from the real experiences of Anastasiia and her friends and family when she actually interviewed people, and it spoke to me very strongly,” says Svobodová, who not only practises “social-specific theatre”, but literally wrote the book on it (which you can read in its entirety on her website).

“I think social-specific theatre came about as a reaction to site-specific theatre,” Hrab explains. “For site-specific theatre, the space is the main source for the creation; and here, it is the social situation.”

“‘Documentary theatre’ is maybe more known as a term, because ‘documentary’ can mean many different things,” Svobodová says. “People know documentary films, et cetera. But for me, the person, the living human being, is the crucial point of my work. I love to meet people, I talk to people, and most of the work I have done has started from meeting individuals or groups living in specific locations.”

Svobodová started her social-specific theatre journey in the early 2000s, when she spent time with people from many countries—including Chechnya, Angola, Burma, Armenia, Georgia, Belarus, and China—awaiting asylum at a refugee camp in the forests of northern Bohemia.

As she writes in Social-Specific Theatre in Practice, “the aim was to create a theatrical form in which the artists and asylum seekers in the camp would be on an equal level in the creative process. The audience who came to the camp to see the final production could not distinguish artists from refugees on the stage. They all shared a common theme through personal stories.

“During the creation, all residents of the camp became our collaborators.”

As with Eight Short Compositions on the Lives of Ukrainians for a Western Audience, one of Svobodová’s intentions for her refugee-camp work was to find common ground between people whose experiences might seem radically different on paper.

“We all are human beings,” she tells Stir. “We all have the same desires, basically. We all are looking for love, we are looking for a happy life. The loss of home is painful for anybody. It can happen to any of us.”

Svobodová’s theatrical practice is about breaking down the walls that separate audience from subject, putting the viewer directly into the shoes of, say, a mother of three from Angola who has found herself in a refugee camp far away from her husband.

“Basically, the topic for the refugee-camp work was always ‘How do we feel when, for instance, we lose someone?’” Svobodová says. “Loss can be under different circumstances, not only because of war. Maybe you lose someone because you have to move away or you emigrate or whatever. And I believed that when we feel this is our story—we are not coming from war, we are in a comfortable life here in the Czech Republic—it can resonate with the audience. We discovered by doing it, that this is absolutely true. But once we started speaking about big politics, it didn’t work at all.”

Eight Short Compositions on the Lives of Ukrainians for a Western Audience

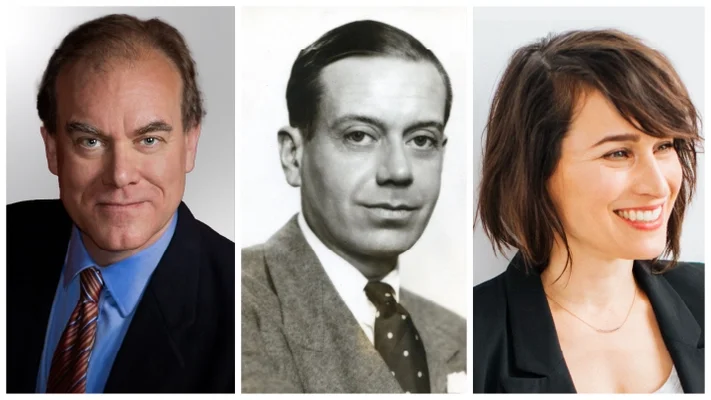

To help bring Eight Short Compositions to life, Svobodová tapped into the talents of Dutch violinist and theatre artist Rosa Berman, Irish actor Amanda Doherty, Swedish-Norwegian musician Lotta Karlsson, London-based multidisciplinary performer Zov Vélez, and Ukrainian theatre producer Mariia Kosiichuk.

“This international team created a unified response to what was happening in Ukraine,” says Hrab. “It is not like ‘We Czechs do our interpretation.’ It’s more emotional—the empathy of people from different communities, different nations, toward what is happening in Ukraine.”

While the cast relates the stories collected by Kosodii—all perform live onstage, with the exception of Kosiichuk, who appears via recording—the text is projected in Ukrainian and English. The staging is kept to a minimum, a choice intended to let the words alone carry the weight. As Svobodová explains, her goal has never been to turn the hardships of others into entertainment.

“What was clear to me from the very beginning was that I cannot take these painful experiences—of people escaping from war, let’s say, in refugee camps—and just make them beautiful for the audience,” she says. “This is not what I wanted to do.”

Nor is Eight Short Compositions meant to be a political statement. At its core, it’s about human resilience in the face of unimaginable events—but Kosodii also clearly has a deep well of compassion for our four-legged friends.

“For me, one of the strongest moments in Anastasiia’s text is when she speaks about cats,” Svobodová says. It’s impossible to say exactly how many pets have been abandoned or displaced by the ongoing conflict, but estimates range from 100,000 up into the millions. “When the war started, the media started to speak about and show the dogs that were running around, not knowing where to go. If you have a dog, this will touch you, because it shows how the normality of life was destroyed.” ![]()