Film review: Make Me Famous travels back to 1980s East Village to rediscover artist Edward Brezinski

Documentary screening at VIFF Centre uncovers a driven artist, and immerses viewer in an art scene that included Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring

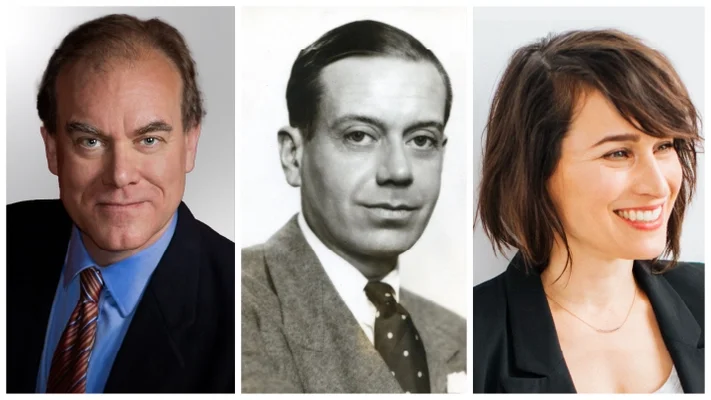

Edward Brezinski in Make Me Famous.

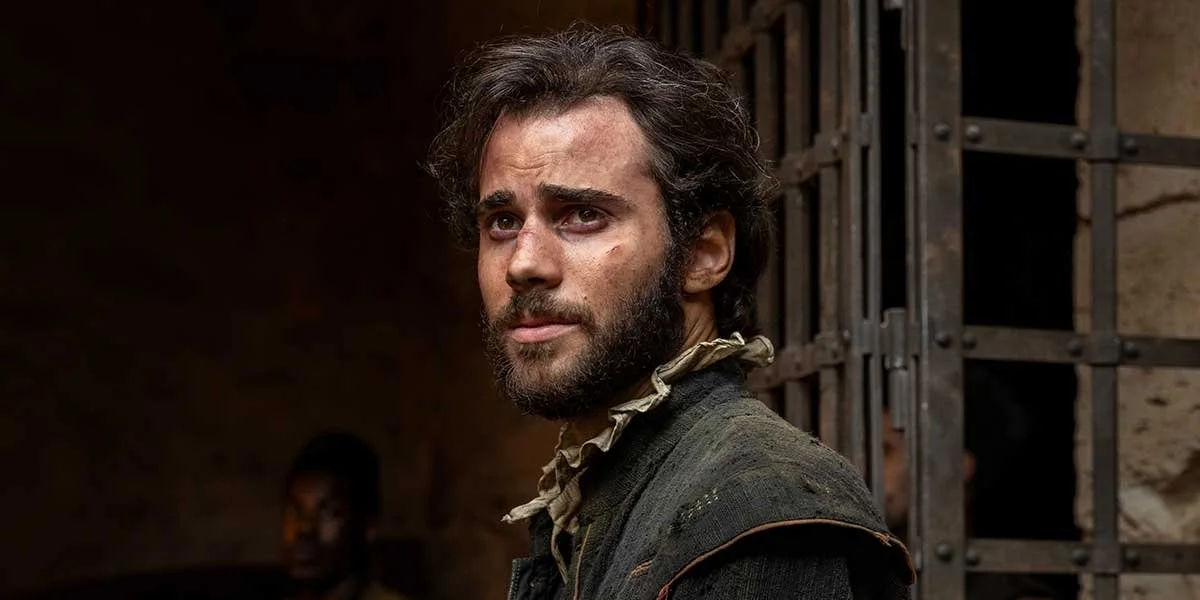

A self-portrait by Edward Brezinski, from Make Me Famous. Photo ©red splat productions

Make Me Famous screens at the VIFF Centre from August 1 to 6

FOR ALL THE BASQUIATS, Scharfs, and Harings who built fame from the squalor of New York’s East Village, there are hundreds of others lost to history.

Mysterious, reckless, and driven, painter Edward Brezinski might have been largely forgotten, beyond a few sharp-eyed collectors. It’s gratifying, then, that the documentary Make Me Famous resurrects his work with a new appreciation. Along the way, the expansive film—full of eccentric, bitchy characters, fascinating tangents, and ’80s-vintage neon intertitles and synth music—immerses the viewer in the beyond-gritty art scene of 1980s New York.

Much of Brezinski’s existence on the Lower East Side was the warehouse art-party circuit, and a wealth of video and photographs from that era capture celebs like Debbie Harry, Robert Mapplethorpe, Andy Warhol, and, yes, Haring and Basquiat in the background of that scene.

The film begins in the early-’80s Bowery, where brooding, charismatic Brezinski inhabits a rundown studio in a building that is literally crumbling, with a homeless shelter across the street. In his rough, expressionistic style, the young, gay artist captures those down-and-out figures on canvas, while creating other haunting portraits that reveal the torment and angst of their subjects—and the times.

An impressive array of the artists who survived the era—Kenny Scharf, Marguerite Van Cook, James Romberger, Claudia Summers, and former Vancouverite and “Shadowman” creator Richard Hambleton, not to mention Brezinski’s dapper, straight-outta-the-Victorian-era ex David McDermott—dish dirt on Brezinski’s own chaotic Magic Gallery and legendary night spots like Club 57. Soon a tragic trifecta of AIDS, heroin, and mental illness takes a toll on the community—but not before it’s discovered by SoHo galleries. (In one of his most infamous acts, the frustrated Brezinski threw a glass of wine on famed gallerist and Basquiat discoverer Annina Nosei, on hand here with her side of the story; in another, he chomped on one of artist Robert Gober’s resin doughnuts—and was rushed to hospital as a result.)

The film’s title refers to the fact that, as one interviewee puts it, Brezinski had a “mania to be noticed” as an artist. But he lived in grinding poverty, often spending the only money he received from selling his works on more paints. In the long tradition of artists unappreciated in their lifetime, he went into self-imposed exile in Europe, experienced homelessness and alcoholism, and died alone, in obscurity, in 2007.

Poignantly, it’s in the posthumous final act of the film that director Brian Vincent retraces Brezinski’s rural Michigan upbringing and interviews art experts who discuss the way Brezinski exemplified the New York Expressionist movement. His cutting portrait of Nancy Reagan, her face skull-like in her signature blood-red suit, now hangs at MoMA (which finally staged a show called Club 57 in 2017, in tribute to the era). Those images and countless anecdotes help you get to know the real Brezinski—but, to the film's credit, not so much that they detract from his enduring mystique. ![]()

Janet Smith is founding partner and editorial director of Stir. She is an award-winning arts journalist who has spent more than two decades immersed in Vancouver’s dance, screen, design, theatre, music, opera, and gallery scenes. She sits on the Vancouver Film Critics’ Circle.

Related Articles

Nettie Wild’s projected and VR-headset works include a mesmerizing three-channel ode to herring migration, the salmon-run-themed Uninterrupted, and “moving paintings”

When an alien invasion threatens a remote town in Nunavut, three teenage girls must save the day

In series at The Cinematheque, vintage home-movie glow of Kyuka: Before Summer’s End and hallucinatory shades of Harvest reveal tension and crisis beneath domestic and communal surfaces

Diane Kurys’s gossipy, subtly performed biopic portrays the last years of a legendary relationship rife with destructive compulsions

Drawing major buzz for the way it plays with genre, the story of a misguided superfan boasts maximalist visual touches, hits of dark humour, and a considerable amount of heart

Vancouver-based Tristin Greyeyes finds inspiration in her grandmother’s story in documentary at GEMFest

Views and feats to inspire, from a Women Mountaineers program at The Cinematheque to the Everest tales of adventure filmmaker Elia Saikaly

At the Rendez-Vous French Film Festival, filmmaker Alexandre Trudeau and star Malia Baker confront anxiety and mortality in the deep freeze of the Prairies

Keeper, Tuner, and Forward join Nirvanna the Band the Show the Movie in prizes for Canada’s top movies of the year

Gourou, Dalloway, and a flick inspired by Liliane Bettencourt of the L'Oréal dynasty help launch 32nd annual fest

Offerings span basketball documentary Saints and Warriors, identity-focused short “One Day This Kid”, and beyond

At VIFF Centre, new Velcrow Ripper and Nova Ami documentary finds women leading residents out of wildfire and flood catastrophes, in Lytton, Yarrow, and beyond

Offerings include features Sirât and Mr. Nobody Against Putin, plus programs for Live Action, Animated, and Documentary shorts

Matt Johnson is back with a chaotic, unabashedly Canadian followup to the cult web series

Visions Ouest and Alliance Française present poignant documentary about a woman retracing her roots to a vibrant but deeply troubled country

Classic film scholar Michael van den Bos hosts evening that mixes vintage film clips with the jazz sounds of the Laura Crema Sextet

Artists like Dee Daniels, Brandon Thornhill, and Krystle Dos Santos are performing around the city this February

In a short documentary, the Vietnamese Canadian queen reflects on becoming the country’s first drag artist-in-residence

Oscar-shortlisted film takes a sweeping, humanistic look at the toll of decades of violence

Retrospective closes with the Japanese director’s melancholic final picture, Scattered Clouds

Visions Ouest screens raucous tale of women ousted from their Quebec rink and ready for revenge, at Alliance Française

Event hosted by Michael van den Bos features Hollywood film projections and live music by the Laura Crema Sextet

Zacharias Kunuk’s latest epic tells a meditative, mystical story of two young lovers separated by fate

Ralph Fiennes plays a choir director in 1916, tasked with performing Edward Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius

A historical adventure about Cervantes and documentaries about a flamenco guitarist and a matador are among the must-sees at the expanded event at the VIFF Centre

Screening at Alliance Française and co-presented by Visions Ouest, the documentary of the folk-rockers’ rip-roaring 2023 show was shot less than a year before lead singer’s death

At the Cinematheque, Bi Gan creates five chapters, told in vastly different visual styles—from silent-film Expressionism to shadowy noir to neon-lit contemporary

Four relatives converge on an old house, discovering the story of an ancestor who journeyed to the City of Light during the Impressionist era

The Leading Ladies bring to life Duke Ellington’s swingy twist on Tchaikovsky score at December 14 screening

Legendary director’s groundbreaking movies and TV work create a visual language that reflects on some of film history’s most sinister figures—and mushroom clouds