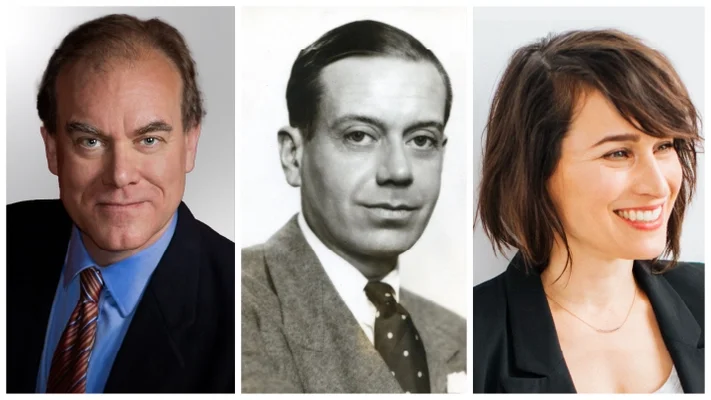

Promoter Tim Reinert energizes local jazz with ever-stronger sense of adventure and diversity

The renowned MC has left his day job to expand his commitment to building jam-packed club nights, bold concert series, and an open door for innovation-hungry young performers and audiences

Tim Reinert

Sun Ra Arkestra, slated to play the Pearl on February 24

TIM REINERT HAS just talked himself out of one job and into a new life—and as local lovers of improvised music all know, talking is something that the affable concert promoter does well. Many will remember him as the pork-pie-hatted host of countless Coastal Jazz and Blues Society shows, charming sometimes unruly audiences and setting them up for much of the Vancouver International Jazz Festival’s most audacious music. More recently, Reinert created and programmed the Infidels podcast, which continues to spread the gospel of creative music throughout the wilderness of the internet.

But talk, as they say, is cheap, and Reinert has gone far beyond being simply a vocal exponent of the music he loves. Ever since the Covid panic eased up and listeners began trickling back to live music, he’s been a one-man employment bureau for musicians across a variety of adventurous genres—and now, having given up his day job with a non-music-related business, he’s about to ramp up his activities to include a growing list of international stars, along with an expanded roster of themed series and jam-packed club nights.

It’s a bold move, but one that’s been a long time coming. Almost since day one, in fact.

Growing up in isolated Kitimat, Reinert was a musical child, blessed with supportive if culturally conservative parents. “I had one of those childhoods where they wanted to make sure I had a lot of different opportunities, so they put me in piano lessons when I was four,” he says. “I had a little bit of aptitude for it, so they put me in vocal lessons not long after that, and I did that for a long time. I did a lot of vocal and piano competitions when I was a kid, and sang in different churches as, like, a boy soprano. But it was very much like an obligation thing; it wasn’t something that I really enjoyed.”

Performing got more interesting for the young Reinert when he reached junior high school and was convinced by his band teacher to switch over to drums. Rock ’n’ roll was verboten in the Reinert household, and even the radio was discouraged, but somehow jazz snuck in under the parental radar once said teacher handed over some instructive mixtapes. “Most of it was jazz, specifically big-band stuff like Buddy Rich and Duke Ellington,” Reinert notes. “That was the beginning for me, and I fell in love really hard and really early.

“It wasn’t something where there was a lot of it around,” he adds. “It was just something that I found myself. And because jazz was this music that my parents didn’t really understand, it was perfectly fine for me to listen to. So it was music that I just became more and more drawn to and more and more obsessed with—and specifically, at the time, as a player. I thought that jazz drumming was going to be my career.”

Until he got to the Lower Mainland, that is, and disillusionment quickly set in. One year in the Capilano University jazz program taught him that being the best young jazz drummer in Kitimat was a long way from being a big-city success story. “You need to have a lot of talent in order to do that,” he explains wryly, “and I learned very quickly that I had very little.” At the same time, however, he discovered his true musical passion, the avant-garde, through jazz-history-class exposure to Ornette Coleman’s epochal 1959 recording The Shape of Jazz to Come. The free-jazz innovator’s ability to create meaning out of seeming chaos spoke to him, and a move into record retail coupled with moonlighting as a jazz MC gave him the wherewithal to explore the music from within.

“Listening to it live really affected me,” he says. “I was emceeing for a lot of different concerts of music that I had never heard before, and two people that were really instrumental in this for me were François Houle and Tony Wilson. Just being arbitrarily assigned to introducing their shows and listening to this music and going ‘There’s far more to this music than I’d thought. There are no boundaries to this. All you need are big ears and creativity, and the music is yours to do with it what you want.’

“So I was involved with the scene,” he continues, adding that the Glass Slipper jazz club, the Hard Rubber Orchestra, the late pianist Paul Plimley, and Coastal Jazz and Blues artistic director Ken Pickering also served as mentors. “I think I got into it at the right age. Like, at an early enough age that I wasn’t kind of hamstrung by the rules. When you get to listen to music like that when you’re 18, 19 years old, and you get told that it’s as valid as Hank Mobley or Miles Davis or whoever, it’s a big deal. And I think I was very fortunate to be able to kind of grow up in it. But I was never really fully invested, because I always felt that as a non-player I was a bit of an imposter. I had imposter syndrome. So I would emcee, I would help where I could, but I really didn’t feel like I had earned any real right to be part of the scene in any real way.”

Enter the Infidels podcast, and a Davie Street nightclub that offered him the chance to produce a regular jazz night.

“We sold out the first one, and sold out the second,” he recalls. “We did, I think, five or six in a row and sold them all out, and I started to realize that this whole thing about needing more live music here wasn’t just me. It wasn’t just me bring selfish; it was a real thing. And that’s when I started to do what I still follow today, which is to create different series at different venues in town, and have each of those series fill a different niche and be geared towards a different audience. So we started a series at the Lido which was all about young and developing musicians, and we started a series that still exists called The New Thing, which is all about avant-garde and free music, which is a passion of mine. And it just started snowballing after that.”

In 2026, a partnership with commercial concert producers Modo Live Entertainment will see Reinert and Infidels Jazz hosting such major stars as the always mind-blowing Sun Ra Arkestra (at the Pearl on February 24), post-rock instrumental supergroup Tortoise (at the Pearl on March 6), and guitar great Pat Metheny (at the Centre in Vancouver on April 27). The entire month of May will be given over to celebrating the 100th anniversary of the birth of Miles Davis, with similar if smaller tributes slated for fellow centenarians Tony Bennett, Randy Weston, and John Coltrane. Meanwhile, Reinert will be overseeing 11 ongoing concert series at nine separate venues, and will continue to help program his comic frenemy Cory Weeds’s Jazz at the Bolt mini-festival, at the Shadbolt Centre for the Arts on February 14 and 15. (Reinert might also be having some impact on Weeds’s personal taste; in a recent interview the mainstream maven revealed that he’s been enjoying a boxed set of LPs from avant-jazz sax screamer Pharoah Sanders.) Somewhere in the middle of this, the Infidels Jazz record label plans to double its output with a further four—or perhaps five—releases. Who has room for a day job, anyway?

Reinert’s early obsession with jazz drumming has likely helped with all of these undertakings, because his timing is perfect. Post-Covid, listeners have been hungry for live music, and it’s also apparent that a generational shift is taking place. Genre distinctions have broken down, the corporatization of pop has become increasingly obvious, and a new, younger audience has emerged that’s unconstrained by the anti-jazz biases of the hair-metal and punk-rock years. We’re now in a place where radical jazz is cool again, although still a minority taste, and Reinert has become its leading local apostle.

“My favourite part is seeing hundreds if not thousands of people coming to jazz concerts that weren’t coming five years ago,” he says. “People who aren’t experts, who maybe don’t know who Miles Davis is and don’t care who Duke Ellington is, but do care about getting a live experience that they can’t get elsewhere. That’s my favourite part of it: being able to facilitate that relationship between the audience and the musicians.

“I try to throw the door open as far as I can to as many musicians as I can, and because of that it looks like Vancouver,” he adds. “The audience looks diverse and like people from all sorts of backgrounds, because that’s who lives here and that’s who plays here. The more wide-open you can make the door for performers, the wider the door is going to be for consumers—and it feels more sustainable because it’s organic. It’s real; it’s not because of any mandate from grants or anything like that. It’s really simple: we just have as many kinds of musicians play our shows as humanly possible—and at the end of the day, there’s really nothing cooler than going to a jazz club.” ![]()