Music review: Heavenly singing in Vancouver Opera’s Rigoletto lights up a dark Victorian world

Easing off some of the more disturbing themes and melodrama, the production feels somehow lighter, stripped-down, and relatably human

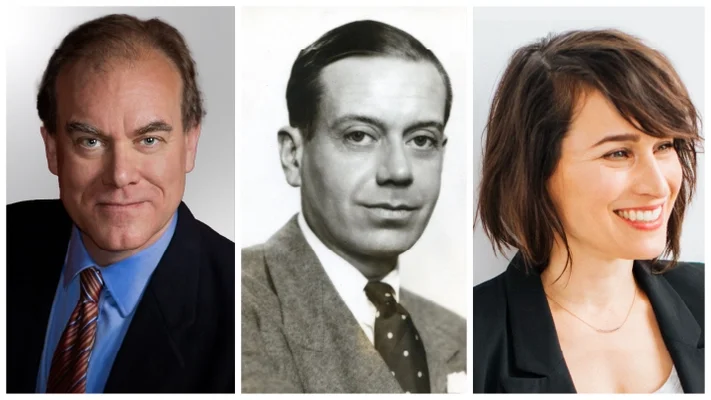

Sarah Dufresne as Gilda and Michael Chioldi as Rigoletto in Vancouver Opera’s Rigoletto. Photo by Emily Cooper

Vancouver Opera presents Rigoletto at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre on October 30 and November 2

VANCOUVER OPERA’S SEASON-OPENING production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto puts its own stamp on a classic, with its two strong leads standing out against a dark Dickensian world.

Instead of playing a lurching humpback, veteran New York baritone Michael Chioldi strikes an almost gentle-giant quality here—not as the traditional embittered court jester, but as a kind of everyman custodian for a “gentleman’s club” in this version reimagined in the Victorian era. Outfitted in a simple grey vest and pants, and walking with a slight limp and cane, his Rigoletto is less the traditional outsider here. The character navigates rage, resilience, despair, and love.

He’s also wholeheartedly protective of his daughter Gilda: she’s played by the staggeringly talented Canadian soprano Sarah Dufresne, who delivers 24-carat clarity in her polished high notes and coloratura. There’s delicacy to her Gilda, complicated by defiant adolescent fire and shattering regret. Together, they have some gorgeous duets—his earthy power set against her angelic heights.

Stage director Glynis Leyshon helmed an almost polar-opposite Rigoletto for the VO in 2009—memorable for its stylized vision, a macabre carnival that included a striking (and slightly controversial) cage set. Here, she eschews some of the more disturbing themes of sexual abuse and stigmatization. Despite the dark, gas-streetlamp-lit setting, this Rigoletto is lighter, stripped-down, and more relatable than usual. For better or worse, even the Duke of Mantua (Yongzhao Yu) comes off as a bit more of a good-time rogue than the usual malevolent sexual predator.

The story (originally set in 16th-century Mantua) starts in the men’s club, where Rigoletto makes fun of a statesman whose daughter has been seduced by the Duke of Mantua—only to have that statesman lay a curse on him. Later, the same Duke seduces Rigoletto’s innocent daughter, Gilda; the humiliated father becomes bent on revenge, while Gilda still naively loves the Duke, leading to tragedy.

Vancouver Opera’s Rigoletto. Photo by Emily Cooper

The Victorian setting seems to underline the hypocrisy of the era, as a gigantic portrait of prim Queen Victoria sternly watches over the men’s depravity. In this co-creation with Pacific Opera Victoria, James Rotondo’s set is criss-crossed with metal walkways and features a semi-raked stage that resembles an abstract cobblestone city map pulled up at the corner. Think of it as a reference to the urban area that male powerbrokers have drawn up, and that the Duke rules over. (Watching the tuxedoed men suck up to his every whim, it’s impossible not to think of Trump’s fanboys in the House of Representatives.) The stripped-down design moves fluidly from the club into the streets outside Rigoletto’s home, and then to the foggy riverside where the final tragic act occurs.

The spotlight in this production remains on Verdi’s emotionally intense music. Under the baton of Jacques Lacombe, the orchestra leans into the Italian composer’s bigger moments, but knows when to pull back and let the lyrical singing shine. It shows thoughtful restraint in moments such as Rigoletto’s horror at being cursed, and finds nuance in the way it conjures the final act’s ominous thunderstorm.

It’s a wonder to watch the confidence with which Chioldi inhabits the title character; when he pleads with the men who have carried Gilda off to the Duke, he moves masterfully from brute fury to vulnerability, begging from his soul. Other highlights include the men’s chorus roaring into action early in the first act, and Act 3’s spectacular quartet “Bella figlia dell’amore”, in which Emma Parkinson’s spicy Maddalena holds her own with Chioldi, Dufresne, and Yu. And Dufresne’s “Caro nome” aria is a showstopper. The audience was rapt as she played with the tempo and nuances of the famously ornamented jewel—opening effortlessly into the stratospheric notes, and sounding like an exquisite bird in the coloratura. In the a cappella section, it was like a spell had been cast on even the fidgetiest audience members.

The effect, in this well-realized production, is that the beauty of that singing and the characters’ humanity glows like gaslight in a dark world. ![]()