Dance review: Flowing forms and abstract storytelling in Royal Winnipeg Ballet double bill

T’əl: The Wild Man of the Woods heralds an exciting new voice, while Carmina Burana strips the work down to its essence

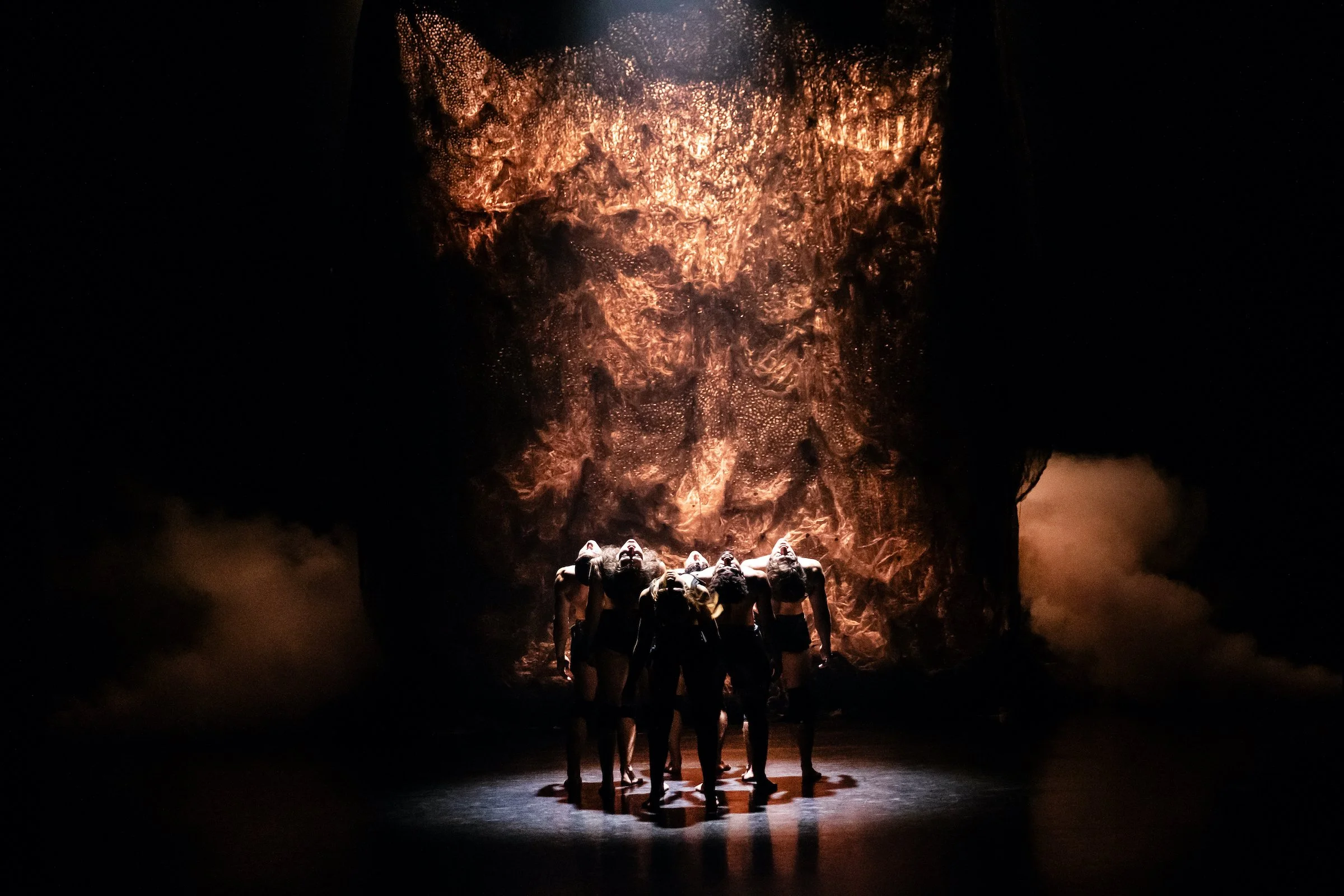

Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s Carmina Burana. Photo by Daniel Crump

Royal Winnipeg Ballet presents Carmina Burana and T’əl: The Wild Man of the Woods at the Centre in Vancouver to February 10

IT’S BEEN A DECADE since the Royal Winnipeg Ballet brought something other than its classic Nutcracker to a Vancouver stage. And the company’s brief appearance this week at the Centre in Vancouver offers a welcome look beyond narrative dance to more abstract works that are strongly rooted in classical technique—a contrast to the edgier, contemporary excellence of our own Ballet BC.

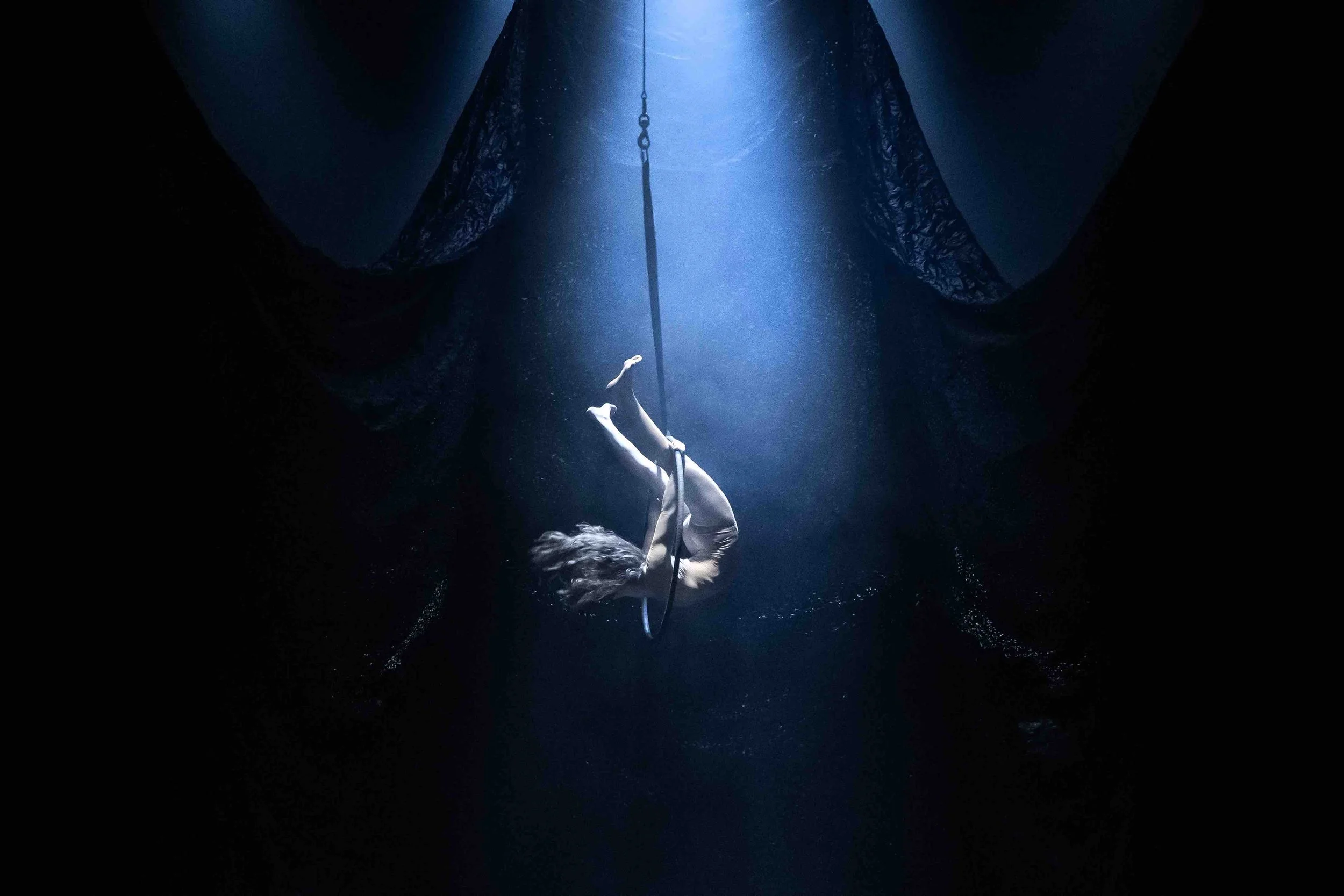

The technically rigorous, polished double bill of T’əl: The Wild Man of the Woods and Carmina Burana opens with an important new work by B.C.–raised Tla’amin artist Cameron sinkʷə Fraser-Monroe.

In T’əl, the rising artist reinterprets an age-old Indigenous story through the language of flowing ballet in surprisingly stripped-down, striking form. Passed down through generations, the tale challenges the Grimm brothers for sinister details: T’əl grabs children, totes them off to the forest in a basket made of snakes, sticks them to the ground with tree sap until he’s ready to roast and eat them. In Fraser-Monroe’s execution, many of those details become abstracted—T’əl is less a movie monster than a shadowy presence, and the plot is suggested through flowing dancers dressed in Asa Benally’s warm cedar-tone costumes and carved out by Scott Henderson’s atmospheric lighting.

T’əl’s great strengths are the warm, unaffected voiceover of storytelling Elder Elsie Paul, sometimes in English, sometimes in Ayajuthem, as well as cellist Cris Derksen’s haunting, driving score that mixes sinister strings, pow-wow drums and chants, and electroacoustic flourishes. Highlights of the choreography include Fraser-Monroe’s gorgeous morphing formations—multiple arms folding delicately around each other to create single, fluttering organisms onstage. Other abstracted moments include a troupe of dancers en pointe who transform into a cloud of black, swirling “no-see-ums”.

T’əl: The Wild Man of the Woods. Photo by Daniel Crump

It feels like only the beginning of an entire new way of interpreting ballet, and signals a long, rich career to come for Fraser-Monroe.

The RWB’s older work Carmina Burana, by Argentinian choreographer Mauricio Wainrot, takes a similar, stripped-down approach to a piece that often attracts outsized set pieces and bawdy action. (Just over 20 years ago, Ballet BC staged a John Alleyne version that culminated in an apocalyptic downpour of black feathers and dead crows; other stagings have included gargantuan clocks and drunken monks.)

The ritualistic moments find bodies crouching in billowing skirts, straight arms propelling them into endless, powerful turns. Later, athletic lifts suggest crosses and stars. About the only set pieces are a series of contemporary-feeling screens on wheels that cleverly become upright beds for a series of couples in one memorable moment.

Wainrot is less interested in Carmina’s Latin textual content than in masterfully channelling the rhythms, soaring vocals, and eclectic wind and xylophone bursts into fluid, modern ballet. As for the work’s famous hedonism, it’s toned down. Even one of the most erotically charged moments, of a woman straddling a man, becomes beautiful: a crowd lifts the copulating bodies skyward, while a chorus of dancers circle hand in hand, turning the entire scene in a twirling mobile sculpture.

A note that without a live performance of the music, the ballet can feel slightly less biblically scaled in its intensity. (In a Ballet Estable rendition of Wainrot’s same work I caught a few years ago at the storied Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, several choirs sang from the balconies and a full orchestra played beneath the dancers.)

Still, especially in its partnering and lifts, there is some thrillingly gorgeous dancing here, the work building to a dizzying finale.

Perhaps the biggest revelation in the evening is how versatile and unifiying the nonliteral language of ballet can be, here reinterpreting age-old stories from different parts of the world: the musings of 14th-century monks and the boogey-man stories passed down through generations of Indigenous people. ![]()

Janet Smith is founding partner and editorial director of Stir. She is an award-winning arts journalist who has spent more than two decades immersed in Vancouver’s dance, screen, design, theatre, music, opera, and gallery scenes. She sits on the Vancouver Film Critics’ Circle.

Related Articles

T’əl: The Wild Man of the Woods heralds an exciting new voice, while Carmina Burana strips the work down to its essence

The Dance Centre and O.Dela Arts present the piece that draws on the performers’ Indigenous ancestors

One-day gathering for artists, educators, and choreographers explores how leadership can be more responsive to the dance world

Rising Tla’amin choreographer Cameron sinkʷə Fraser-Monroe draws on a tale he heard growing up for a large-scale work that joins Carmina Burana on a double bill

Fun riffs on the classic include a moose-headed Bottom wearing buffalo plaid and an appearance by a royal couple

In this PuSh Fest, Music on Main, and Dance Centre premiere, humming songs, whispered words, and hypnotic movement bring a sense of serenity and connection to a chaotic world

With staging that evokes a Chicago jazz bar, the Dance Centre and PuSh Festival co-presentation draws on matrilineal fashion and line dancing

Program features Pite’s Frontier, a deep dive into the unknown, and Kylián’s 27’52”, an exploration of theoretical elements

In a riveting PuSh Festival and New Works copresentation, Belgium’s Cherish Menzo plays with repetition, chopped-and-screwed music, and flashing dental grillz

In DanceHouse and The Cultch co-presentation, the Hungarian company is full of flowing bodies and rippling fabric

In the deeply moving production, dancers embody the ancient tale of death and longing by tapping into their own experiences of tragedy

Productions that “push” forms include dance works that play with props and stereotypes, as well as ethereal odes to nature and the northern lights

Producer Natália Fábics says the Hungarian work, co-presented by DanceHouse and The Cultch, is as much a contemporary artwork and philosophical epic as a fusion of circus and dance

Choreographer’s latest creation is a dazzling blend of dance, lighting, and sound that draws on her Black matrilineal heritage

Big bands play West African music with guests Dawn Pemberton, Khari McClelland, and others

Electrifying performance reclaims hyper-sexualized “video vixen” of hip hop’s golden era

Festival brings live performances, conversations, and community workshops to the Scotiabank Dance Centre and Morrow

Chimerik 似不像 and New Works XR partner to continue the online festival with new artistic producer Caroline Chien-MacCaull

Provocatively reimagined endings to opera and Shakespeare were among the random scenes that stuck with us from the year onstage

Having steered the company toward full houses and extensive touring, French-born dance artist will leave after 40th-anniversary season

Set to a score by Mendelssohn, whimsical show puts a Northern Canadian twist on Shakespeare’s timeless comedy

The Leading Ladies bring to life Duke Ellington’s swingy twist on Tchaikovsky score at December 14 screening

Amid tulle tutus and fleecey lambs, director Chan Hon Goh reflects on the history of the “feel-good production”

Hungarian dance-circus company invites audiences to witness a visceral, mesmerizing spectacle set in the aftermath of a destroyed world

Pond hockey, RCMP battles, and polar bears bring this unique rendition home—with classic Russian touches, of course

Company’s annual holiday twist on The Nutcracker features a flavoursome assortment of styles, from classical ballet to hip hop to ’60s swing

Dreamlike Taiwanese show explores freedom and oppression, with Ling Zi becoming everything from spiky weapons to shivering life forces all their own

Presented by DanceHouse, Taiwan’s Hung Dance draws on the headpieces of Chinese opera to conjure calligraphy, weapons, and birds in flight

The local arts and culture scene has bright gifts in store this season, from music by candlelight to wintry ballets

New production comes as a result of the street dancer’s Iris Garland Emerging Choreographer Award win earlier this year