Created with survivor testimonials, The Mush Hole tells the truth about Canada’s longest-running residential school

Renowned Indigenous choreographer Santee Smith brings her haunting yet hopeful piece to The Cultch and Urban Ink’s TRANSFORM Festival

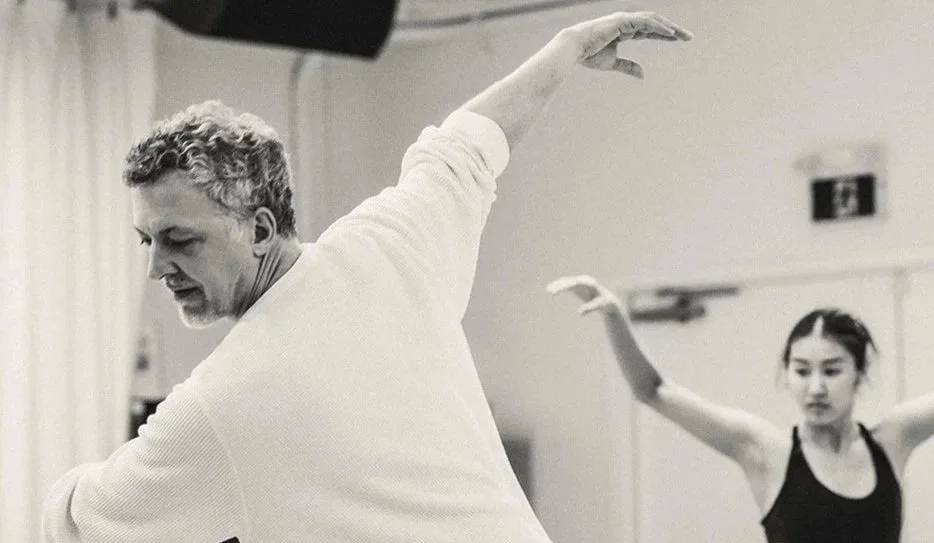

The Mush Hole. Photo by Ian Maracle

The Cultch and Urban Ink present Kaha:wi Dance Theatre’s The Mush Hole at the Historic Theatre from November 14 to 16 as part of TRANSFORM Festival

ONE HUNDRED AND forty-two years—that’s how long the Mohawk Institute, Canada’s longest-running residential school, was in operation before its doors finally shut in 1970. Located just outside Brantford, Ontario, it was referred to as the Mush Hole within the Six Nations of the Grand River community because of the gruel the children were forced to eat there day after day.

Survivor testimonials from those who attended the school are a pivotal part of The Mush Hole, a production by internationally recognized dance artist Santee Smith, who is from the Kahnyen’kehàka (Mohawk) Nation, Turtle Clan from Six Nations of the Grand River. Blending dance and theatre with haunting, cinematic imagery and an all-Indigenous cast, the piece sets Mohawk Institute survivors’ truths onstage for audiences to witness.

Speaking to Stir by phone, Smith says she was hesitant to work on The Mush Hole at first because of her personal connection to the subject matter. She has family members who attended the Mohawk Institute—but has zero information about their time there, other than the long-term impacts it has had on her family. So an important aspect of her creation process was to invite other survivors into the studio to observe the dancers’ rehearsals, offer their reactions, and share memories of their own time in the Mush Hole.

“It was told to us that a big pot was made at the beginning of the week, and they ate the whole thing throughout the week,” Smith says. “Sometimes it was really bad by the end of the week; they were scraping the bottom of the pot, and it’d been there forever. At the time, it was a working farm, but the produce from the farm was not given to the students. They ate mush.”

Smith’s own company, Kaha:wi Dance Theatre, will bring The Mush Hole to the Historic Theatre from November 14 to 16, in a copresentation by The Cultch and Urban Ink as part of this year’s TRANSFORM Festival. The piece premiered in 2020, winning five Dora Mavor Moore Awards.

During the residential school’s operation, there was a plentiful orchard out front with trees bearing bright-red apples. The survivors’ memory of those fruit trees is one of many that Smith has woven into The Mush Hole.

“Apples appear in the performance, symbolic of that longing for nourishment and not having it,” the choreographer says. “The students were not allowed to eat the apples, so survivors say that they were in a constant state of hunger….They were always trying to find ways to get food—not only for themselves, but for the younger students.”

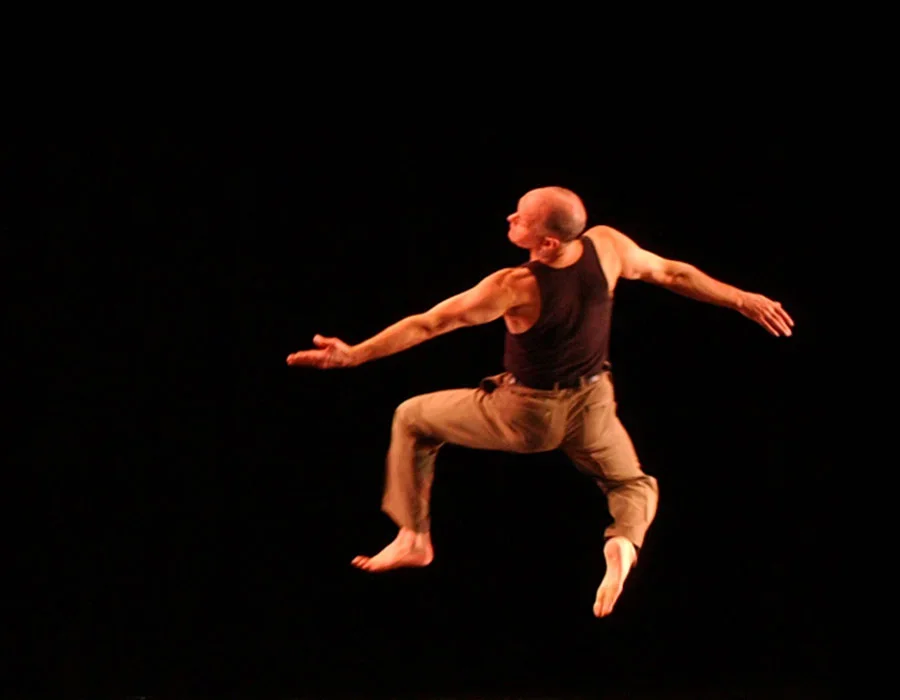

The Mush Hole. Photo by Thomas Boethe

In 1972, the Mohawk Institute building was reclaimed by the Six Nations and repurposed as the Woodland Cultural Centre, a space for Indigenous knowledge revitalization. Smith began working on The Mush Hole in 2016, when the centre and the University of Waterloo approached her about creating a piece in response to the Mohawk Institute site. She collaborated with staff at the centre to consult archives and books, attend publicly held survivor talks, and have one-on-one conversations with survivors.

The result is a vignette-style piece in which the stage is divided into three architecturally inspired sections: the centre is the main building, the left is the girls’ side of the school, and the right is the boys’ side. Elsewhere during the show, different areas of the Mush Hole—from the cafeteria to the laundry room—are created in order to re-enact memories.

“We’re really bringing in the brick and mortar of the school and the experiences that happened in each room,” Smith says. “For example, ‘The Boiler Room’—that’s the name of our scene—is the old basement boiler room where abuse took place, particularly for the boys. Because of the loudness of the boiler, noises or screams or calls were not heard. The score, as well, sounds like a basement boiler room, so sonically, it gives that context for the audiences.”

By “brick and mortar”, Smith means that actual bricks from the Mohawk Institute are included in the production. In 2016, the building was in a state of disrepair, and a referendum went out to the community to decide whether it should be demolished. An overwhelming majority voted to restore it—and when that process began, there were discarded bricks lying all around the site. Smith was able to collect some for the production.

The bricks have been made into small crosses, with numbers written on each one—11, 34, 17—as that was how the children were referred to while they were attending the institute. Abolishing Indigenous names was yet another means for the church to strip the children of their cultural identity. Many of the kids, says Smith, would carve their numbers into the brick walls at the back of the school, along with how many years they had been there, as though they were serving time in a prison.

None of the abusers, whether principals, custodians, teachers, or other authority figures, are onstage characters in The Mush Hole. Instead, shadows and gestures are used to convey the effect of their violence on the children, emphasizing that this is really a story about the survivors.

“You have to walk the fine line between telling the truth and giving a glimpse of the devastation and the horrific treatment onstage, but we’re not taking it to a place where it can be super triggering,” Smith says. “Although it can be for people who are really close to that material or have not dealt with that in their lives.”

Santee Smith in The Mush Hole. Photo by Thomas Boethe

Smith is known for her biting, captivating works that are grounded in Indigenous culture and stories. Her group piece Blood Tides is part of a triptych that reaffirms the reproductive power of women, while her solo NeoIndigenA sees her dance with deer, elk, and moose antlers to explore the soul’s relationship to living elements. In the broader artistic community, Smith was appointed a member of the Order of Canada in 2023 and is the current chancellor of McMaster University.

Right from the beginning, The Mush Hole has been about listening to survivors’ stories. Smith says that even now that the show has toured three times, she still seeks feedback and wants to know how survivors respond to seeing the work. At times, says the dance maven, hearing the survivors’ stories has been humbling.

“It was important for us all to hear it, not just me as the choreographer, because we were embodying their truth,” she says. “Being able to talk to them directly, you know, it was high-stakes emotional as the survivors were sharing their stories—for them, and also for us to receive that. But it was also in a way, as we performed the piece, very cathartic—and very important that their stories get shared.”

The Mush Hole is performed by three Indigenous youths who portray children at the school, alongside Smith and one other adult performer, who represent parental figures—an elder generation of survivors.

“We often hear about how it affected the children, which is really important,” Smith says. “But the stories of what happened to them after they came out and had families, and that legacy of the intergenerational trauma…I really wanted to embody that and really focus on it, showing that it’s going to take generations to recover from the school’s impact. So that was really important. And as a mother, I can’t imagine what it would be like to have your children taken away.”

Smith’s daughter, singer-songwriter Semiah Kaha:wi Smith, portrayed one of the youths in The Mush Hole when the production premiered. Though she’s now 26 and no longer performs in the piece, her vocals are still featured on the soundtrack.

It’s one subtle moment of intergenerational connection that is emblematic of an important theme in The Mush Hole—hope.

“Towards the end,” Smith shares, “there’s a big pinnacle moment where the couple are able to connect and to hold hands and walk forward.…It shows the overarching resilience of those people’s experience. That happened—yet people are continuing, regaining their culture, restoring, rebuilding. [It shows] the strength of the people that endured that and continued on.” ![]()